Become a catalyst of good work and unite with others committed to making our organisations a little better!

validation

Homo Economicus is Dead — Long Live Homo Cooperativus!

Before embarking on the journey, please read our piece about the need for a new paradigm to create good work and flourishing organisations.

can businesses create good work? (Click on the icon for pdf)

We have looked everywhere - the infamous 'homo economicus' has gone missing like Ötzi the Iceman! This abstract model of men who act and decide solely based on rational calculation of benefits and costs, and who are exclusively guided by self-interest, or even greed and guile, exists mostly in the heads of economists (who, by the way, are 80% male!) and corporate finance departments. Behavioural economists, anthropologists and psychologists have proven and re-proven in experiments and field studies all over the world that humans naturally "care about fairness and reciprocity"; are "willing to change the distribution of material outcomes at personal expense"; and "are inclined to reward those who act in a cooperative manner while punishing those who do not" - notwithstanding the cost to themselves (Henrich et al 2001). As it happens, even in so-called "one-shot" games with complete strangers, positive mutual interactions quickly emerge…

Jump to

What is Good Work?

Learning Journey

Core Concepts (click icons to jump to discovery)

What is "good work"? (7)

What does it mean to enable 'good' work? How does flourishing differ from happiness, well-being or welfare?

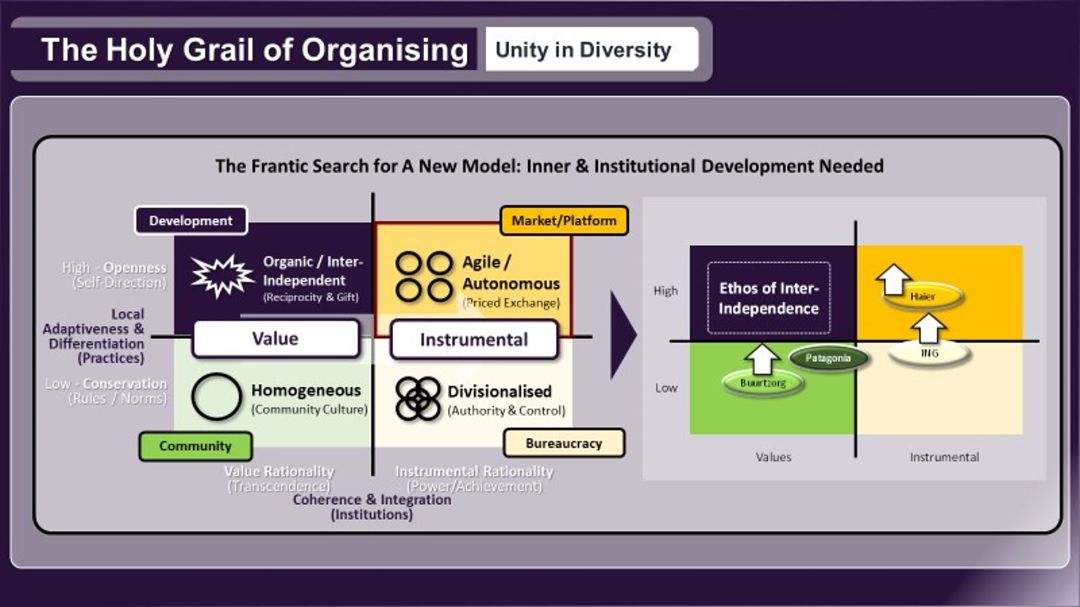

Are innovative organisations always better? (8)

Make yourself familiar and "browse" through concepts such as sociocracy, holacracy, rendanheyi, teal and others. Ask yourself what practical and ethical challenges these are facing.

How to craft good organisations? (9)

What are some initial ideas to "operationalize" goodness in organisations, to enable social flourishing and a 'good life through and at work'?

How can we detect if organisations are genuinely good?

Based on all of the above, note down some personal reflections in your journal.

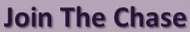

Good Organisations in 10 Minutes: From Agility to Excellence

Our Perspective On Core Concepts

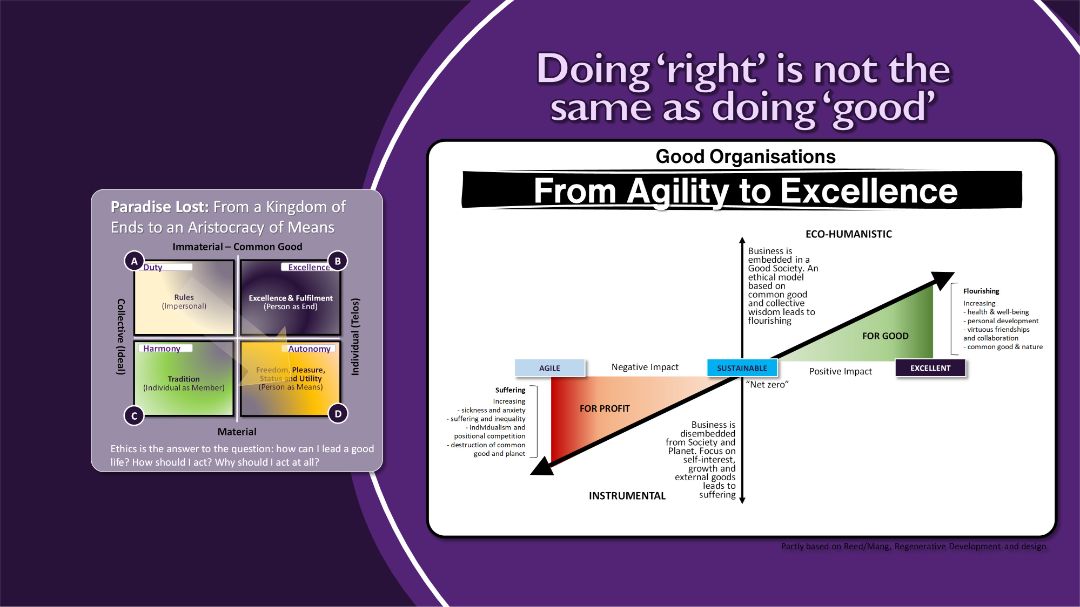

“The firm is not only a money making machine. That is a reductionist perspective. The firm is above all a political agent: an agent of positive transformation of the context and reality in which the company operates.” ― Stefano Zamagni

Flourishing By Design?

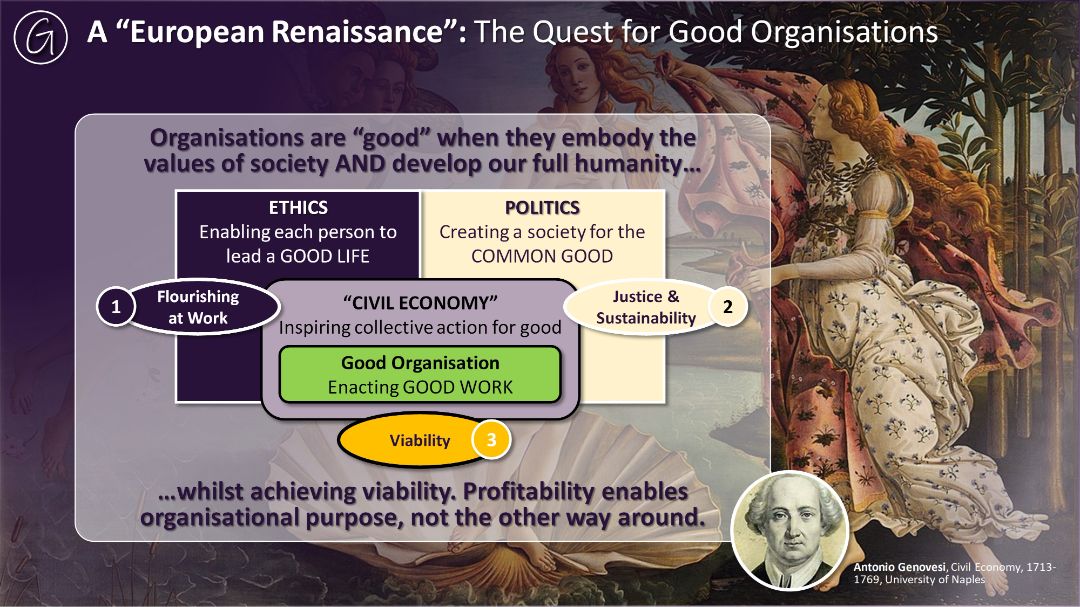

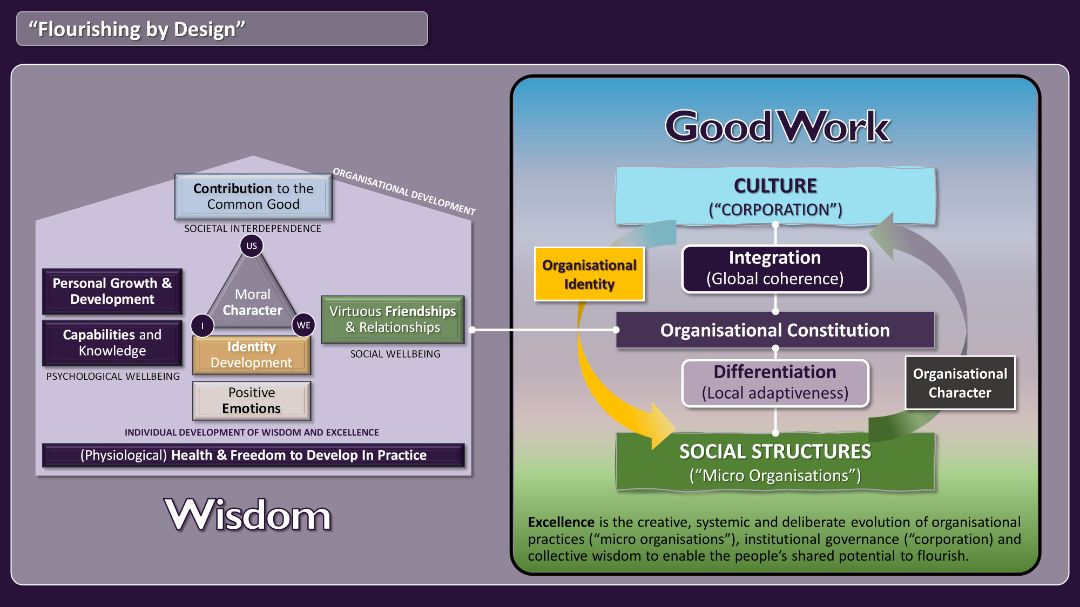

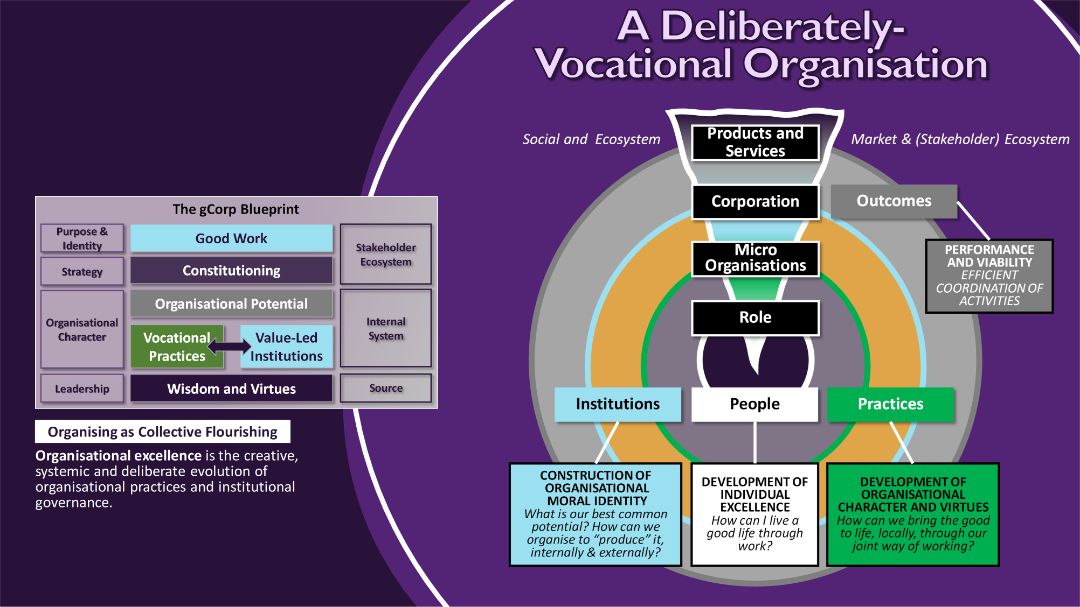

As we journey deeper into our quest for good organisations, it becomes increasingly clear that embodying responsibility isn't a straightforward task. Many of the popular alternatives to capitalism fall short in addressing the core issues we face. Trapped within a neoliberal framework and driven by an instrumental-utilitarian perspective, these approaches often overlook fundamental questions: What is the true purpose of our economy, and how can work truly be considered good?

We firmly believe that the economy is inseparable from society, and therefore its purpose should be to facilitate dignified and meaningful human life within a community. In other words, the economy cannot operate in isolation from moral considerations; its legitimacy is intricately linked to its ability to positively impact society and enable individuals to lead fulfilling lives together. However, asserting moral principles is one thing; translating them into organizational structures is quite another. To bridge this gap, we must solidify our understanding of "social ontology" – how social systems can be conceptualized. From there, we can begin to translate our ethical foundations into principles, structures, and practices that can bring about our vision of social flourishing.

A word of warning: It's important to note that we're now venturing into the realm of philosophy and politics. Many of the questions we're grappling with have puzzled philosophers for centuries, with no clear-cut answers. As such, we cannot promise definitive solutions. Our goal is simply to ignite your curiosity and inspire you to explore further. You'll find a wealth of perspectives in the discovery section below.

Below you can also find a few blog posts that dive into our evolving thoughts around these concepts

Discover New Puzzle Pieces of Wisdom On A Search For Eureka Moments!

Materials marked in dark purple are foundational. Those flagged in light purple are for in-depth exploration.

Core Concept 7: Good Work

Core Concept 7: Good Work

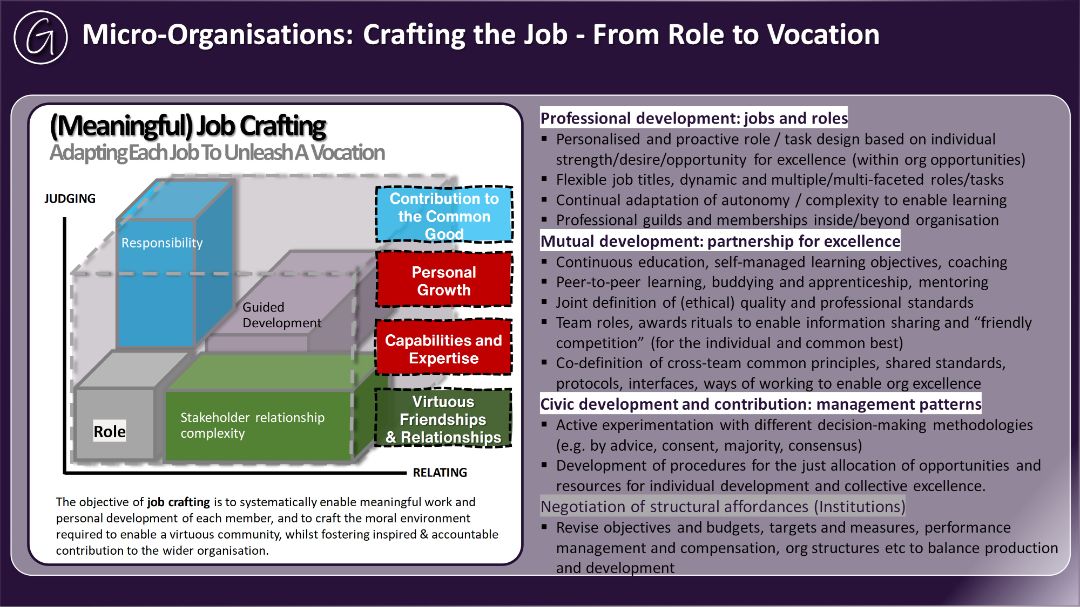

Please reflect What is Good work? What are the alternative theories for meaningful and good work? What is enabling, what is destroying meaningful and good work?

1) What is good and meaningful work from a virtue ethics perspective?

2) What are the main characteristics of good work from the medical/health, the positive organizational scholarship, the SDT, the human resource development and the political point of view? What are the enablers and blockers of good work in these perspectives?

3) Good work is always integrated into the good organisation (core concept 9) and the good economy (core concept 5). Once you have covered all these concepts try to understand how good work is enabled through these social structures and in turn is changing these social structures into the right direction.

But first: an attempt to define "flourishing" in more details (all draft - related to performance management)

Core Concept 8: Popular theories to develop better organisations

Core Concept 8: What are the (many) popular theories to design better organisations?

Make yourself familiar and "browse" through concepts such as sociocracy, holacracy, rendanheyi, teal and others and ask yourself what ethical challenges these are facing.

1) What are the essentials of organisation design? And what are the requirements for designing organisations for the 21st century?

2) Can you describe the characteristics of the different "cracies" named here. How do these differ?

3) If you consider all suggested organisational designs

Core Concept 9: How Do Good Organisations Differ?

Core Concept 9: How do good organisations differ?

1) A core distinction of good organisations is between virtues, practices and institution. Can you define each of these and explain how these relate? Can you give examples from your own experiences how institutions sometimes undermine good work and virtues (in practices)?

2) Can you explain how the good organisation is contributing to the good life of all along examples you find in the articles?

The Great Philosophers: An Introduction to Western Philosophy

Ethics and Excellence: Cooperation and Integrity in Business

After Virtue: A Study in Moral Theory

Political Ideologies: An Introduction

An Introduction to Political Philosophy

Civil Economy: Another Idea of the Market

Meaningful Work

Work Redesign

Good Work

The Craftsman

The Oxford Handbook of Meaningful Work

Dialogic Organization Development

Small Arcs of Larger Circles

Critical Systems Thinking and the Management of Complexity

Cynefin - Weaving Sense-Making into the Fabric of Our World

The Fearless Organization

Humanocracy: Creating Organizations as Amazing as the People Inside Them

Many Voices One Song

Reinventing Organizations

Open Strategy: Mastering Disruption from Outside the C-Suite

Start-up Factory: Haier's RenDanHeYi model and the end of management as we know it

Zero Distance: Management in the Quantum Age

The Fractal Organization: Creating sustainable organizations with the Viable System Model

Platform for Change

Leading by Weak Signals: Using Small Data to Master Complexity:

The Agile Organization: How to Build an Innovative, Sustainable and Resilient Business

Holacracy: The Revolutionary Management System that Abolishes Hierarchy

Designing Organizations: Strategy, Structure, and Process at the Business Unit and Enterprise Levels

Collective Power: Patterns for a Self-Organized Future

Restoring Sanity: Practices to Awaken Generosity, Creativity, and Kindness in Ourselves and Our Organizations

Corporate Rebels: Make work more fun

Joy, Inc.: How We Built a Workplace People Love

The Character Of A Corporation

The Neurotic Organization

From Dependency to Autonomy: Studies in Organization and Change

Transforming Experience in Organisations: A Framework for Organisational Research and Consultancy

Understanding Organizations-Finally!

The Firm as a Collaborative Community: The Reconstruction of Trust in the Knowledge Economy

Virtue at Work: Ethics for Individuals, Managers, and Organizations

Corporate Governance and Ethics: An Aristotelian Perspective

.

.