4 Reasons Why New Narratives Cement the Old Status Quo and Avoid the Real Work - and Why Good Is the New Black

In the beginning organisational purpose was just a word, synonymous with 'mission' or 'goal'. And few took note. Then, suddenly, it transmuted into a signal of enlightenment, of consciousness, of virtue. Of growing up. In an era of disruption and anxiety, it became fashionable for global corporations to 'come out' to the world and declare how they had, eventually, found 'proper' meaning, deep inside themselves…

Since then, battalions of Fortune 500 companies have recast themselves from self-interested profit maximisers - single-mindedly exploiting human and natural resources - into, allegedly, mature and trustworthy corporate adults: 'purpose-driven', redeemed, re-born… Organisations of all kinds are competing for the most glamorous purpose statement or millenniophile branding campaigns: construction companies are providing "people with tools to build a better world"; advertising behemoths are "taking care of the world's information, for all of us", fashion retailers are handing out #BeKind t-shirts…

Sadly, in spite of much pompous rhetoric and the occasional progress, it all is mostly fake news. Whilst executives are perching together at business roundtables or in alpine resorts, busily celebrating themselves and the end of business's misanthropic adolescence, many companies are - often wilfully - sidestepping the urgently required deeper reflection about the "purpose of business". In fact, Corporate Irresponsibility remains ubiquitous. Only when negative externalities cause public outrage, do captains of industry suddenly turn introspective, loudly professing their eternal loyalty to humanistic values and pledging to endorse - of course voluntary - initiatives to clean up the mess they created in the first place. If Corporatelandia wants to really start accepting accountability for the world, it must stop abusing and instrumentalising "purpose for their own purpose".

But what does that mean? We set out to examine the purpose puzzle through four especially problematic lenses - partly connected, but hopefully each stimulating in its own right…

[Part 1] The Separation Fallacy: It's The Morality, Stupid!

In the beginning organisational purpose was just a word, synonymous with 'mission' or 'goal'. And few took note. Then, suddenly, it transmuted into a signal of enlightenment, of consciousness, of virtue. Of growing up. In an era of disruption and anxiety, it became fashionable for global corporations to 'come out' to the world and declare how they had, eventually, found 'proper' meaning, deep inside themselves…

Since then, battalions of Fortune 500 companies have recast themselves from self-interested profit maximisers - single-mindedly exploiting human and natural resources - into, allegedly, mature and trustworthy corporate adults: 'purpose-driven', redeemed, re-born… Organisations of all kinds are competing for the most glamorous purpose statement or millenniophile branding campaigns: construction companies are providing "people with tools to build a better world"; advertising behemoths are "taking care of the world's information, for all of us", fashion retailers are handing out #BeKind t-shirts…

Sadly, in spite of much pompous rhetoric and the occasional progress, it all is mostly fake news. Whilst executives are perching together at business roundtables or in alpine resorts, busily celebrating themselves and the end of business's misanthropic adolescence, many companies are - often wilfully - sidestepping the urgently required deeper reflection about the "purpose of business". In fact, Corporate Irresponsibility remains ubiquitous. Only when negative externalities cause public outrage, do captains of industry suddenly turn introspective, loudly professing their eternal loyalty to humanistic values and pledging to endorse - of course voluntary - initiatives to clean up the mess they created in the first place. If Corporatelandia wants to really start accepting accountability for the world, it must stop abusing and instrumentalising "purpose for their own purpose".

But what does that mean? We set out to examine the purpose puzzle through four especially problematic lenses - partly connected, but hopefully each stimulating in its own right…

[Part 1] The Separation Fallacy: It's The Morality, Stupid!

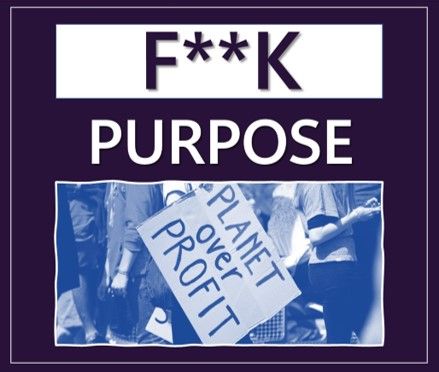

The question of 'purpose' in business is not just important, but existential. It relates to two important queries: firstly, why do businesses exist? And, more importantly, how should they act in practice, and for what end? The first is a question of morality, the second of ethics.

Until recently, answers were - at least in the neoliberal Western hemisphere - straightforward: businesses should simply do whatever it takes to make as much money as possible, for their shareholders. Yet things have changed. Today, even die-hard 'Friedmaniacs' acknowledge that such teleopathy has become untenable. With the planet burning and employees burning out, politicians and public demand more responsible businesses and more meaningful jobs - causing headwinds and headaches in corporate headquarters and marketing departments!

Also due to the increased scrutiny, business ethics, until recently confined to tedious academic seminars, papal encyclicals and dusty tombs of ethical codes - or subject to pitiful mockery ("isn't business ethics an oxymoron?"), is making a buoyant comeback. However, Alicia Hennig, a renowned scholar for business ethics and expert in comparative moral philosophy, cautions that the very notion of "business ethics" is problematic: it appears to imply that there is a separate ethics for business, which of course is silly. Morality and values, applicable to society at large, pertain - in exactly the same way - to organised work. There is only "Ethics IN Business", not ethics OF business. Ethics is about what we value, how we should treat each other, who we want to become. In other words, ethics is "Us", with a capital "U". It is a fallacy to assume that the economy resides in its own bubble.

In fact, as we have recently written elsewhere, economics was never originally envisaged as a separate field of inquiry, but rather a discipline sandwiched somewhere between philosophy and politics. It was Friedrich Hayek who "broke with two centuries of precedent and declared that economics is 'in principle independent of any particular ethical position or normative judgments'" and an 'objective' science, in precisely the same sense as any of the physical sciences". Since then, "economics ceased to be a technique - as Keynes believed it to be - for achieving desirable social ends'. Sadly, Alicia acknowledges, businesses and business schools alike have devotedly cultivated the myth of amoral markets and businesses. Still today, many business ethicists are management researchers who consistently commence from that false premise.

What does that mean for purpose? Above all, it means that purpose is already there! Businesses are "intermediate associations", as Alejo Sison writes, organs of society. As such, they must always act first and foremost to enable, uphold and express the morality of the society that created them, and serve the common good. Like a mini society, businesses "embody" societal purpose.

Therefore, purpose is, above all, an existential way of "being together" in business, as humans, and not about outcomes. The question is not: "What would the world miss if your company did not produce it?", but "what is your unique contribution to the society you are part of", "how does your business 'enable' a good society"? We do not cease to be human beings, Alicia moots, when we enter the factory or office door. And as Immanuel Kant warned us two centuries ago - we paraphrase: humans and humanity must never be treated as means to make profit. In spite of much hype, the 'future of work' is not a question of 'who we need to become at work', but 'who we want to become through work'. It is our businesses, not its workers, that must adapt to serve the human condition.

We know what you think. Undoubtedly, companies must perform, produce, and be competitive - that is true. But let's not fool ourselves. Commercial success might be necessary for survival, but we are not ethical, just because we generate returns. We must reflect more deeply on our axiological judgments - what value means, whom we create value for and what it says about us. If we mistake mammon for morals, and separate work from life, we do so at our own peril. Already Max Weber suggested that our desire to pursue wealth is caused by salvation anxiety - the "disenchantment" of the Enlightenment left humanity without a discernible path to the divine. Yet, earthly achievements can never fill the spiritual void. Drowning in consumerism, our postmodern culture suffers from unhappiness, self-doubt, and fear of failure. Our task is to recover a more beautiful vision of a modern, pluralistic, thriving society. Not by producing more, but by being more. We become "good", when we act with humanity, integrity and caring for each other and a higher purpose, at work and in life. If business wants to restore public trust, it must stop mixing morality with marketing!

[Part 2] The individualism Fallacy: Corporations Are Not (quite) Like 'Living Beings'

The question of 'purpose' in business is not just important, but existential. It relates to two important queries: firstly, why do businesses exist? And, more importantly, how should they act in practice, and for what end? The first is a question of morality, the second of ethics.

Until recently, answers were - at least in the neoliberal Western hemisphere - straightforward: businesses should simply do whatever it takes to make as much money as possible, for their shareholders. Yet things have changed. Today, even die-hard 'Friedmaniacs' acknowledge that such teleopathy has become untenable. With the planet burning and employees burning out, politicians and public demand more responsible businesses and more meaningful jobs - causing headwinds and headaches in corporate headquarters and marketing departments!

Also due to the increased scrutiny, business ethics, until recently confined to tedious academic seminars, papal encyclicals and dusty tombs of ethical codes - or subject to pitiful mockery ("isn't business ethics an oxymoron?"), is making a buoyant comeback. However, Alicia Hennig, a renowned scholar for business ethics and expert in comparative moral philosophy, cautions that the very notion of "business ethics" is problematic: it appears to imply that there is a separate ethics for business, which of course is silly. Morality and values, applicable to society at large, pertain - in exactly the same way - to organised work. There is only "Ethics IN Business", not ethics OF business. Ethics is about what we value, how we should treat each other, who we want to become. In other words, ethics is "Us", with a capital "U". It is a fallacy to assume that the economy resides in its own bubble.

In fact, as we have recently written elsewhere, economics was never originally envisaged as a separate field of inquiry, but rather a discipline sandwiched somewhere between philosophy and politics. It was Friedrich Hayek who "broke with two centuries of precedent and declared that economics is 'in principle independent of any particular ethical position or normative judgments'" and an 'objective' science, in precisely the same sense as any of the physical sciences". Since then, "economics ceased to be a technique - as Keynes believed it to be - for achieving desirable social ends'. Sadly, Alicia acknowledges, businesses and business schools alike have devotedly cultivated the myth of amoral markets and businesses. Still today, many business ethicists are management researchers who consistently commence from that false premise.

What does that mean for purpose? Above all, it means that purpose is already there! Businesses are "intermediate associations", as Alejo Sison writes, organs of society. As such, they must always act first and foremost to enable, uphold and express the morality of the society that created them, and serve the common good. Like a mini society, businesses "embody" societal purpose.

Therefore, purpose is, above all, an existential way of "being together" in business, as humans, and not about outcomes. The question is not: "What would the world miss if your company did not produce it?", but "what is your unique contribution to the society you are part of", "how does your business 'enable' a good society"? We do not cease to be human beings, Alicia moots, when we enter the factory or office door. And as Immanuel Kant warned us two centuries ago - we paraphrase: humans and humanity must never be treated as means to make profit. In spite of much hype, the 'future of work' is not a question of 'who we need to become at work', but 'who we want to become through work'. It is our businesses, not its workers, that must adapt to serve the human condition.

We know what you think. Undoubtedly, companies must perform, produce, and be competitive - that is true. But let's not fool ourselves. Commercial success might be necessary for survival, but we are not ethical, just because we generate returns. We must reflect more deeply on our axiological judgments - what value means, whom we create value for and what it says about us. If we mistake mammon for morals, and separate work from life, we do so at our own peril. Already Max Weber suggested that our desire to pursue wealth is caused by salvation anxiety - the "disenchantment" of the Enlightenment left humanity without a discernible path to the divine. Yet, earthly achievements can never fill the spiritual void. Drowning in consumerism, our postmodern culture suffers from unhappiness, self-doubt, and fear of failure. Our task is to recover a more beautiful vision of a modern, pluralistic, thriving society. Not by producing more, but by being more. We become "good", when we act with humanity, integrity and caring for each other and a higher purpose, at work and in life. If business wants to restore public trust, it must stop mixing morality with marketing!

[Part 2] The individualism Fallacy: Corporations Are Not (quite) Like 'Living Beings'

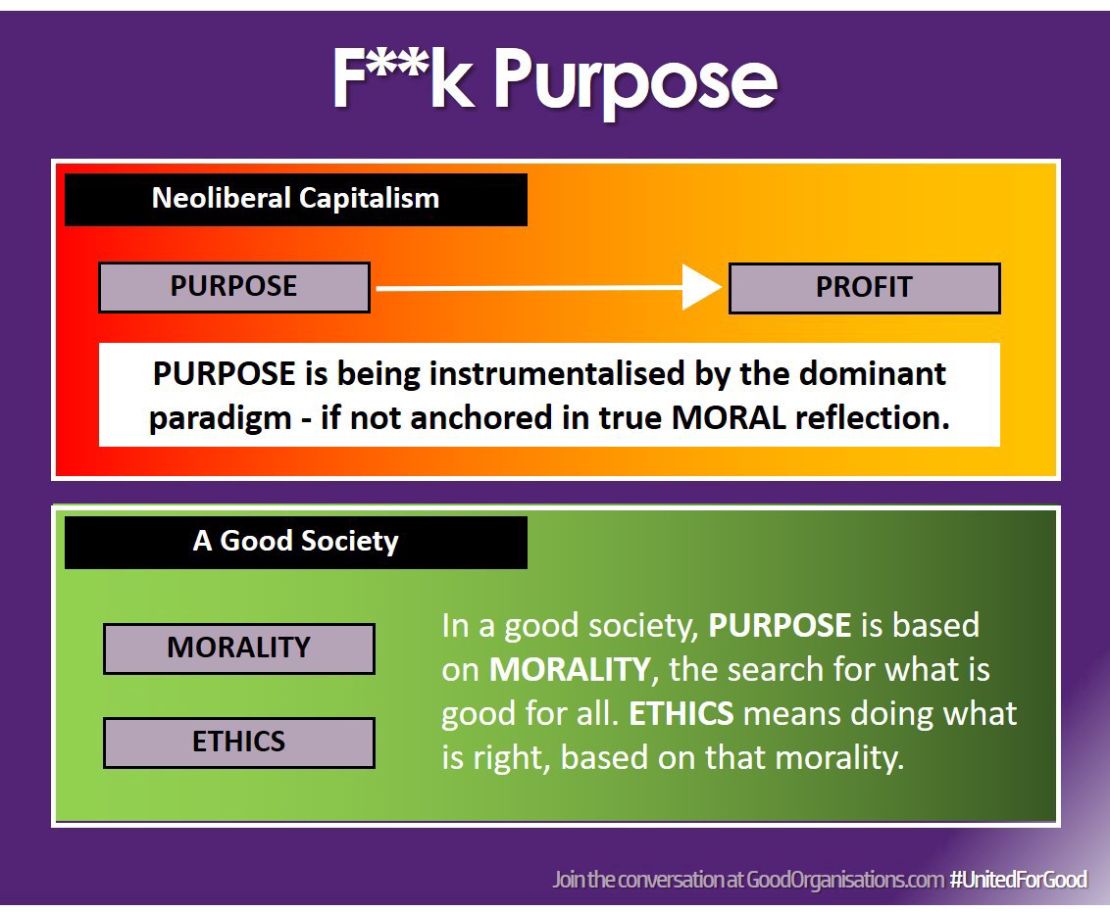

Image: Cogito, ergo sum. Or Not. (Source: internet)

The second fallacy relates to our use of language: we often conflate 'meaning' and 'purpose' as synonymous, but they are not. The question of 'meaning' of life is a late 19th Century invention, and reflects a growing emphasis on the individual and its inner state. It has often displaced the previously dominant question about - you guessed it - the 'purpose of life'.

The shift is far-reaching: It is the difference between asking "what might make me feel fulfilled, given my circumstances", and "what is my life for", "what should fulfil me qua human being" - in light of the world that exists. The latter is not simply a question of hedonic preferences or taste, but a question of morality - of what is essentially good, what the human life is for; and of ethics - of how we should act (together) in order to attain a good life. Conversely, the question of meaning is by definition self-referential and personal. We all make our own meaning, based on what our life represents for us - including our feelings, emotions, consciousness, motivation.

When we use meaning and purpose interchangeably in business, it is often based on the seductive metaphor of the organisation as a "living being". Like self-determined, autonomous adults, who thanks to continuous and deliberate self-optimisation, allegedly, earn meaning in their lives, so - supposedly - do corporations. Unfortunately, this not only perpetuates a false ideal of individual freedom, intended mainly as freedom from interference, and thus seeks to legitimise corporate sovereignty, self-governance and voluntarism, but also conveniently deflects from the embeddedness of organisational life and the need for deeper reflection about collective morality.

As Victor Frankly once pointed out: Individual "freedom is only part of the story and half of the truth. Freedom is but the negative aspect of the whole phenomenon whose positive aspect is responsibleness. In fact, freedom is in danger of degenerating into mere arbitrariness unless it is lived in terms of responsibleness." The question is: what is freedom for? Both as people and organisations, we cannot find purpose inside ourselves, but acquire purpose by taking up our role in society, within the ecosystem. We become purposeful by being part of a greater whole. Hence, purpose always requires us to establish common norms of morality and shared purpose - we must let go of our independence and step into mutual interdependence, even if that proves to be difficult.

Paraphrasing the unforgettable Bill Sloane Coffin: "Meaning is a matter of personal attributes and preferences, purpose a matter of public policy. Meaning seeks to make sense of the effects of life, purpose seeks to attain the essence of life. Meaning in no way affects the status quo, while purpose leads inevitably to political confrontation. Meaning is only a waystation on the road to purpose."

And maybe the meaning-purpose dichotomy leads us again beyond questions of language - perhaps we must reconsider "how to think". Seduced by technological progress and the increasing commodification of life, our very process of thinking has become condensed into a calculative, rational device to get from A to B. Thus, we live in a world of things "already reified into a network of pre-defined ends". Ironically, thus the triumph of reason is the demise of being - we are annihilating our own souls. In order to remain human, as Heidegger claimed, we must re-learn to "dwell" in our thoughts - like the "Flaneur" of Baudelaire. We must reconnect "thinking with being", in order to reenchant our lives. Sadly, as Nietzsche declared: "the wasteland grows". It might never have been truer that "human beings [must] strive towards excellence by thinking about thinking."

[Part 3] The System Fallacy: How "Wholeness" Shot Itself in The Foot…

Image: Cogito, ergo sum. Or Not. (Source: internet)

The second fallacy relates to our use of language: we often conflate 'meaning' and 'purpose' as synonymous, but they are not. The question of 'meaning' of life is a late 19th Century invention, and reflects a growing emphasis on the individual and its inner state. It has often displaced the previously dominant question about - you guessed it - the 'purpose of life'.

The shift is far-reaching: It is the difference between asking "what might make me feel fulfilled, given my circumstances", and "what is my life for", "what should fulfil me qua human being" - in light of the world that exists. The latter is not simply a question of hedonic preferences or taste, but a question of morality - of what is essentially good, what the human life is for; and of ethics - of how we should act (together) in order to attain a good life. Conversely, the question of meaning is by definition self-referential and personal. We all make our own meaning, based on what our life represents for us - including our feelings, emotions, consciousness, motivation.

When we use meaning and purpose interchangeably in business, it is often based on the seductive metaphor of the organisation as a "living being". Like self-determined, autonomous adults, who thanks to continuous and deliberate self-optimisation, allegedly, earn meaning in their lives, so - supposedly - do corporations. Unfortunately, this not only perpetuates a false ideal of individual freedom, intended mainly as freedom from interference, and thus seeks to legitimise corporate sovereignty, self-governance and voluntarism, but also conveniently deflects from the embeddedness of organisational life and the need for deeper reflection about collective morality.

As Victor Frankly once pointed out: Individual "freedom is only part of the story and half of the truth. Freedom is but the negative aspect of the whole phenomenon whose positive aspect is responsibleness. In fact, freedom is in danger of degenerating into mere arbitrariness unless it is lived in terms of responsibleness." The question is: what is freedom for? Both as people and organisations, we cannot find purpose inside ourselves, but acquire purpose by taking up our role in society, within the ecosystem. We become purposeful by being part of a greater whole. Hence, purpose always requires us to establish common norms of morality and shared purpose - we must let go of our independence and step into mutual interdependence, even if that proves to be difficult.

Paraphrasing the unforgettable Bill Sloane Coffin: "Meaning is a matter of personal attributes and preferences, purpose a matter of public policy. Meaning seeks to make sense of the effects of life, purpose seeks to attain the essence of life. Meaning in no way affects the status quo, while purpose leads inevitably to political confrontation. Meaning is only a waystation on the road to purpose."

And maybe the meaning-purpose dichotomy leads us again beyond questions of language - perhaps we must reconsider "how to think". Seduced by technological progress and the increasing commodification of life, our very process of thinking has become condensed into a calculative, rational device to get from A to B. Thus, we live in a world of things "already reified into a network of pre-defined ends". Ironically, thus the triumph of reason is the demise of being - we are annihilating our own souls. In order to remain human, as Heidegger claimed, we must re-learn to "dwell" in our thoughts - like the "Flaneur" of Baudelaire. We must reconnect "thinking with being", in order to reenchant our lives. Sadly, as Nietzsche declared: "the wasteland grows". It might never have been truer that "human beings [must] strive towards excellence by thinking about thinking."

[Part 3] The System Fallacy: How "Wholeness" Shot Itself in The Foot…

Lost in Holism. (Image from the Internet)

The third fallacy comes from the world of systems. Have you ever met someone who was overpoweringly advocating "complex adaptive systems", "ecosystems" or "system thinking" as the final solutions for all worldly troubles? Maybe with some garniture of "ecological consciousness", "spiral dynamics" or deep ecology? Well, you are not alone! And, it is not a coincidence that the current 'purpose-mania' is enthusiastically espousing such ideas in the discussion about CSER and purpose…

It is fairly hard to frame the ever-emergent and fast growing 'complexity and systems' movement, due to its varied and often-obscurely technical lingo (wait for the next few lines: revenge is sweet!). That said, many of the passionate systemati embrace some version of, so-called, 'ontological holism'. Their claim is that "environmental and human exploitation are direct consequences of the prevalence of enlightenment (Cartesian, Newtonian, nature/culture) dualism". Somewhat surprisingly, they counter that alleged mistake by quickly introducing yet another strict dichotomy between "complicated" or "simple", and "complex". In their belief, everything is entangled and non-linear. Therefore, only higher consciousness and "post-enlightenment holism" can lead us to a fully integrated, whole and healthy humanity within the ecosphere.

Whilst indisputably stimulating, their ontology quickly becomes normative: only if we think holistically, from the "system" perspective, can we resolve our allegedly "wicked problems". In an attempt to give their conviction more cogency, complexity buffs fabricate a remarkable hodgepodge of mystic-to-magic ideologies centred on "ecosystemic harmony" - merrily combining concepts from system thinking with themes from Daoism or Buddhism, like wu wei and inter-beingness; borrowing old tenets, like bioegalitarianism, from green movements; or indigenous thought and non-anthropocentrism from romanticism; and adaptiveness from pragmatism - whilst mixing everything with a purported need for higher consciousness, the positive psychology imperative of "idiosyncratic self-realisation", and an antagonism to rules…

Unfortunately, whilst many system thinkers express praiseworthy aspirations for the common good, mixing ontological questions with normative axiological claims is highly problematic. In fact, the movement is too swift in turning their conception of reality into a system for morality - opposing dualist ethics, normative morality, universal values, general rules and instead sustaining some vague non-teleological ethic of "individual moral voluntarism". As Alicia Hennig points out: one of the thorny aspects, for example, of Daoism is "the emphasis on relativism due to the concept of constant change, which can be linked to amoralism and moral indifference."

More problematic even, as Andy Scerri argues, is that such a 'normative holism' erodes the focus on differences of interest by diverse stakeholders and the importance of distinct social and institutional structures. Thus, it relativises judgements about ethics and moral agency in relation to questions of environmental and human exploitation, however defined. As a result, the ability for political advocacy is critically diluted. Differences between interests of a global corporation and a participatory democratic state, for example, are played down because the recognition of conflicting interests and the distinction between voluntary ethical and binding political obligations is weakened.

In a nutshell, when carelessly applied, wholeness digs its own hole (pardon the pun!). Undermining collective morality and non-voluntary ethical standards for individuals and businesses is often a bad idea. Before we know it, the narrative of "everything is connected to everything" becomes "no single actor can be accountable" and then "no central intervention or regulation is justified". Thus, ironically, the integral ecological theory leads to a fragmented "vision of a society without collective plans for collective political emancipation", undermining its own call for activism. Maybe, therefore, it comes as no surprise that many global businesses have enthusiastically embraced such language - vocally adopting fashionable and, above all, voluntary ecosystemic policies - like "net positive", "net zero", SDGs, ESGs - which are neither anchored in a consistent or coherent framework of morality, nor requiring them to take highly painful action whilst keeping regulation at bay.

Paradoxically, if we indeed accept that in a holistic paradigm our individual pursuit of excellence can never become part of a concerted and intentional design of a good society, then we can only hope that the common good will magically emerge from "self-organizing spontaneity of the universe" and "voluntary individual initiatives aiming at fragmentary problems". If history is a good predictor of the future - in spite of much pathos and passion from the new age systemicados - that is not likely to happen anytime soon…

[Part 4] The Knowing-Doing Fallacy: Purpose Is a Verb, Not a Noun!

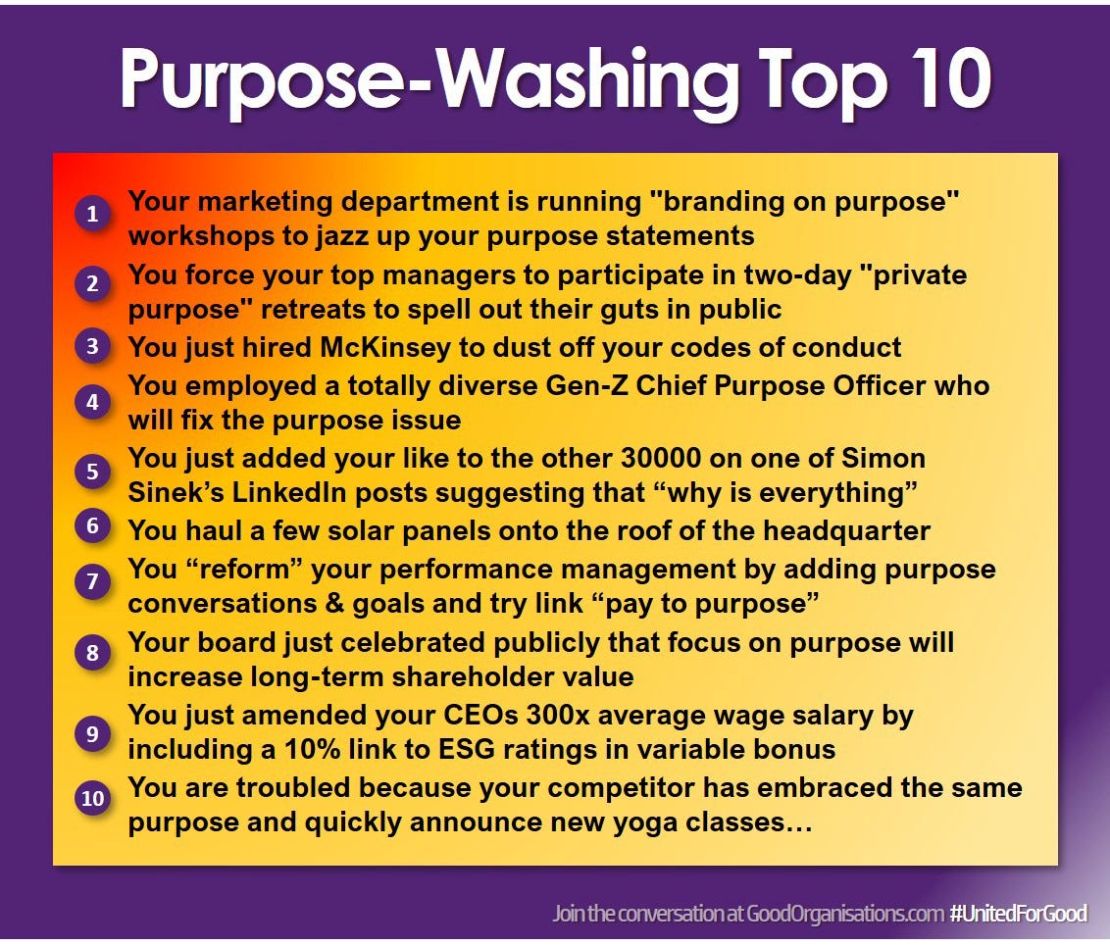

A final point needs to be made in regards to the aforementioned and somewhat awkward renaissance of business ethics. As Alicia Hennig highlights, another source of trouble is when organisations and their leaders treat ethics as "an add-on". Here are 10 dead sure symptoms that you are on the wrong track:

Lost in Holism. (Image from the Internet)

The third fallacy comes from the world of systems. Have you ever met someone who was overpoweringly advocating "complex adaptive systems", "ecosystems" or "system thinking" as the final solutions for all worldly troubles? Maybe with some garniture of "ecological consciousness", "spiral dynamics" or deep ecology? Well, you are not alone! And, it is not a coincidence that the current 'purpose-mania' is enthusiastically espousing such ideas in the discussion about CSER and purpose…

It is fairly hard to frame the ever-emergent and fast growing 'complexity and systems' movement, due to its varied and often-obscurely technical lingo (wait for the next few lines: revenge is sweet!). That said, many of the passionate systemati embrace some version of, so-called, 'ontological holism'. Their claim is that "environmental and human exploitation are direct consequences of the prevalence of enlightenment (Cartesian, Newtonian, nature/culture) dualism". Somewhat surprisingly, they counter that alleged mistake by quickly introducing yet another strict dichotomy between "complicated" or "simple", and "complex". In their belief, everything is entangled and non-linear. Therefore, only higher consciousness and "post-enlightenment holism" can lead us to a fully integrated, whole and healthy humanity within the ecosphere.

Whilst indisputably stimulating, their ontology quickly becomes normative: only if we think holistically, from the "system" perspective, can we resolve our allegedly "wicked problems". In an attempt to give their conviction more cogency, complexity buffs fabricate a remarkable hodgepodge of mystic-to-magic ideologies centred on "ecosystemic harmony" - merrily combining concepts from system thinking with themes from Daoism or Buddhism, like wu wei and inter-beingness; borrowing old tenets, like bioegalitarianism, from green movements; or indigenous thought and non-anthropocentrism from romanticism; and adaptiveness from pragmatism - whilst mixing everything with a purported need for higher consciousness, the positive psychology imperative of "idiosyncratic self-realisation", and an antagonism to rules…

Unfortunately, whilst many system thinkers express praiseworthy aspirations for the common good, mixing ontological questions with normative axiological claims is highly problematic. In fact, the movement is too swift in turning their conception of reality into a system for morality - opposing dualist ethics, normative morality, universal values, general rules and instead sustaining some vague non-teleological ethic of "individual moral voluntarism". As Alicia Hennig points out: one of the thorny aspects, for example, of Daoism is "the emphasis on relativism due to the concept of constant change, which can be linked to amoralism and moral indifference."

More problematic even, as Andy Scerri argues, is that such a 'normative holism' erodes the focus on differences of interest by diverse stakeholders and the importance of distinct social and institutional structures. Thus, it relativises judgements about ethics and moral agency in relation to questions of environmental and human exploitation, however defined. As a result, the ability for political advocacy is critically diluted. Differences between interests of a global corporation and a participatory democratic state, for example, are played down because the recognition of conflicting interests and the distinction between voluntary ethical and binding political obligations is weakened.

In a nutshell, when carelessly applied, wholeness digs its own hole (pardon the pun!). Undermining collective morality and non-voluntary ethical standards for individuals and businesses is often a bad idea. Before we know it, the narrative of "everything is connected to everything" becomes "no single actor can be accountable" and then "no central intervention or regulation is justified". Thus, ironically, the integral ecological theory leads to a fragmented "vision of a society without collective plans for collective political emancipation", undermining its own call for activism. Maybe, therefore, it comes as no surprise that many global businesses have enthusiastically embraced such language - vocally adopting fashionable and, above all, voluntary ecosystemic policies - like "net positive", "net zero", SDGs, ESGs - which are neither anchored in a consistent or coherent framework of morality, nor requiring them to take highly painful action whilst keeping regulation at bay.

Paradoxically, if we indeed accept that in a holistic paradigm our individual pursuit of excellence can never become part of a concerted and intentional design of a good society, then we can only hope that the common good will magically emerge from "self-organizing spontaneity of the universe" and "voluntary individual initiatives aiming at fragmentary problems". If history is a good predictor of the future - in spite of much pathos and passion from the new age systemicados - that is not likely to happen anytime soon…

[Part 4] The Knowing-Doing Fallacy: Purpose Is a Verb, Not a Noun!

A final point needs to be made in regards to the aforementioned and somewhat awkward renaissance of business ethics. As Alicia Hennig highlights, another source of trouble is when organisations and their leaders treat ethics as "an add-on". Here are 10 dead sure symptoms that you are on the wrong track:

What matters most, is not Why but Who we are.

Busy with such spirited new endeavours to fend off the "great resignation" and botox their corporate image, companies often forget to systematically revise anachronistic power structures, harmful or overpriced products, divisive policies, dehumanising processes, myopic incentives, dreadful cultures, meaningless roles or sinful people. For example, law professors Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita find that none of the signatories of the Business Roundtable declaration in 2019 have seriously changed their corporate governance guidelines or executive pay structures away from shareholder value.

That will not suffice. As our friend Sergio Caredda puts it: "purpose acts both as morality (providing direction of what is good and bad) and ethic (providing the […] alignment of values and culture to support its achievement)". Purpose is a "way of doing business", not meditation classes to attain higher consciousness, value statements on PowerPoints, or supplementary features. And, by the way, it is not even some obtusely formulated ethics handbook - this is where many smug moral philosophers, comfortably dwelling in their academic or religious ivory steeples (many of them priests), have been sorely missing the point. Business ethics cannot be just about theoretical rules of behaviour, but must be operationalised through business. That means calibrating our organisational structures and processes to ensure that the organization, as an entrepreneurial community, is continually developing its character and co-elevating its members to better enable individual development and growth, as well as collective flourishing and societal prosperity. Alicia admits that, unfortunately, "most academics lack practical work experience in organisations. What we think should be done in organisations is very different to what has been done in organisations. The link between theory and practice must urgently be improved."

Talking about building bridges, it is evident that no responsible "corporate citizen" today can afford to continue to act in isolation. Organisations must, together, participate in a collaborative blueprint with other stakeholders to collectively attain sustainable prosperity for all. Beyond structural adjustments, like diverse multi-stakeholder boards, this requires active engagement in an inter-institutional dialogue, outside the gates of stylish 'open space' office buildings. Together, we must face tough questions: How should organisations support democratic governments? Why do some companies not pay taxes? What is the appropriate role of financial institutions? How to contain short-term pressure from stockmarkets? Why do we have more CEOs "called Peter" than female executives? Does modern meritocracy perpetuate an intergenerational autocracy of wealth? Do free markets drive exploitation and oppression? Can property rights cement unacceptable inequality… And many more. As responsible businesses we cannot sweep such challenges under the purpose-washed carpet.

Here, we want to briefly revert to the question of 'meaning vs purpose'. The "thinking-doing gap" also often reflects a specific conceptualisation of self. In fact, we will argue that the "operationalisation" of business ethics in an organisation is not only about the revision of structures and processes, but also requires a shift in the way we construct our individual and collective identity. Let us explain. With the erosion of communities and traditions and the increasing globalisation of our lives, "late-modern societies [do] no longer provide stable "anchor points" for the self". As a result, self-identity has increasingly become an individual "project of self": in the face of ever-changing circumstances, we seek to develop our agency and capacity for self-actualisation in a project of continuous reflective construction. Like mini capitalists, we are optimising and "renewing" our selves in reaction to external forces. Thus, our identity becomes a coping mechanism to keep the impact and anxiety from the unpredictability and chaos of modern life at bay. This quickly leads to a "morality of authenticity" - we start to believe that we can only trust ourselves and our personal freedom of choice. Authenticity thus substitutes dignity: what makes an action good is that it is aligned to our individual desires, "true to ourselves", and can be displayed to others as such.

Such a conceptualisation of self-identity has three inherent problems: it is depriving ourselves of the joy of relational flourishing that only the vulnerability of interdependence can bring; it erodes a moral identity that mediates between individual life and collective purpose; and it weakens our ability to enable positive collective transformation.

In fact, whenever the "reflexive project of the self" becomes hyperindividualistic it leads to the tyranny of the "sovereign self", predicated only on our own internal "core values" and intrinsic life plan. Ironically, though, our identity is fundamentally relational - we only become "self among other selves", as a "person-in system". We need others to discover, define and develop ourselves. Moreover, the very notion of flourishing is dependent on our development with and within a community. As we have argued at the beginning, deeper purpose is related to our role within the wider system - flourishing is a common good. It is co-created between us and others through the way we engage with trust.

This connects to the need for morality - we all exist in a dialogic moral space and must face questions of what kind of lives we want to live, "what it is good to be", in and through our relationships. Authenticity can never suffice here - we can only truly define our own identity in the context of those things that matter for us and others. Hence, moral identity is a mediator in the interplay between individual and society - by the same token, ethics is always about the boundaries of our individual freedom in service of the common good.

Finally, we will argue that an increasing fragmentation of morality and values leads directly to a vicious circle of increasing "wickedness" of our societal issues. As Alan Watkins suggests in "Wicked & Wise", most societal problems are inherently complex because they are SOCIAL problems, i.e. they depend on (ethical) judgment. A quick look at the Stacey matrix reminds us that complexity is directly related to the degree of disagreement in a society - hence, perversely, and we are simplifying here on purpose: the more "authentic" we all become, the more wicked our problems get, and the more we must invest in authenticity to cope with the increasing unpredictability of our lives. We can also look at the same phenomenon from the perspective of our capacity for societal transformation. As Stefano Zamagni reminds us, the neoliberal fantasy of freedom of choice is deeply flawed: we only ever have the freedom to choose from the options available - we can almost never determine what choices are available in the first place. This is exactly where the ability to engage interdependently, as individuals and organisations, in a wider societal blueprint "for good" becomes crucial. If we understand our self-development uniquely as individual adaptation and growing resilience to external changes, we are quickly commoditising ourselves as victim of circumstances, and lose our collective ability to improve society for everybody. Hence, we must beware of a modern desire for authenticity. It can quickly lead to a detachment from the community that holds us, and to the erosion of the moral character that can make us the best we can become. If we want to operationalise true purpose, we must nurture a relational identity, that embraces the committment to community and the moral prospect of a good society for all.

[Part 5] Eudaimocracy - Why Good Is the New Black

What matters most, is not Why but Who we are.

Busy with such spirited new endeavours to fend off the "great resignation" and botox their corporate image, companies often forget to systematically revise anachronistic power structures, harmful or overpriced products, divisive policies, dehumanising processes, myopic incentives, dreadful cultures, meaningless roles or sinful people. For example, law professors Lucian Bebchuk and Roberto Tallarita find that none of the signatories of the Business Roundtable declaration in 2019 have seriously changed their corporate governance guidelines or executive pay structures away from shareholder value.

That will not suffice. As our friend Sergio Caredda puts it: "purpose acts both as morality (providing direction of what is good and bad) and ethic (providing the […] alignment of values and culture to support its achievement)". Purpose is a "way of doing business", not meditation classes to attain higher consciousness, value statements on PowerPoints, or supplementary features. And, by the way, it is not even some obtusely formulated ethics handbook - this is where many smug moral philosophers, comfortably dwelling in their academic or religious ivory steeples (many of them priests), have been sorely missing the point. Business ethics cannot be just about theoretical rules of behaviour, but must be operationalised through business. That means calibrating our organisational structures and processes to ensure that the organization, as an entrepreneurial community, is continually developing its character and co-elevating its members to better enable individual development and growth, as well as collective flourishing and societal prosperity. Alicia admits that, unfortunately, "most academics lack practical work experience in organisations. What we think should be done in organisations is very different to what has been done in organisations. The link between theory and practice must urgently be improved."

Talking about building bridges, it is evident that no responsible "corporate citizen" today can afford to continue to act in isolation. Organisations must, together, participate in a collaborative blueprint with other stakeholders to collectively attain sustainable prosperity for all. Beyond structural adjustments, like diverse multi-stakeholder boards, this requires active engagement in an inter-institutional dialogue, outside the gates of stylish 'open space' office buildings. Together, we must face tough questions: How should organisations support democratic governments? Why do some companies not pay taxes? What is the appropriate role of financial institutions? How to contain short-term pressure from stockmarkets? Why do we have more CEOs "called Peter" than female executives? Does modern meritocracy perpetuate an intergenerational autocracy of wealth? Do free markets drive exploitation and oppression? Can property rights cement unacceptable inequality… And many more. As responsible businesses we cannot sweep such challenges under the purpose-washed carpet.

Here, we want to briefly revert to the question of 'meaning vs purpose'. The "thinking-doing gap" also often reflects a specific conceptualisation of self. In fact, we will argue that the "operationalisation" of business ethics in an organisation is not only about the revision of structures and processes, but also requires a shift in the way we construct our individual and collective identity. Let us explain. With the erosion of communities and traditions and the increasing globalisation of our lives, "late-modern societies [do] no longer provide stable "anchor points" for the self". As a result, self-identity has increasingly become an individual "project of self": in the face of ever-changing circumstances, we seek to develop our agency and capacity for self-actualisation in a project of continuous reflective construction. Like mini capitalists, we are optimising and "renewing" our selves in reaction to external forces. Thus, our identity becomes a coping mechanism to keep the impact and anxiety from the unpredictability and chaos of modern life at bay. This quickly leads to a "morality of authenticity" - we start to believe that we can only trust ourselves and our personal freedom of choice. Authenticity thus substitutes dignity: what makes an action good is that it is aligned to our individual desires, "true to ourselves", and can be displayed to others as such.

Such a conceptualisation of self-identity has three inherent problems: it is depriving ourselves of the joy of relational flourishing that only the vulnerability of interdependence can bring; it erodes a moral identity that mediates between individual life and collective purpose; and it weakens our ability to enable positive collective transformation.

In fact, whenever the "reflexive project of the self" becomes hyperindividualistic it leads to the tyranny of the "sovereign self", predicated only on our own internal "core values" and intrinsic life plan. Ironically, though, our identity is fundamentally relational - we only become "self among other selves", as a "person-in system". We need others to discover, define and develop ourselves. Moreover, the very notion of flourishing is dependent on our development with and within a community. As we have argued at the beginning, deeper purpose is related to our role within the wider system - flourishing is a common good. It is co-created between us and others through the way we engage with trust.

This connects to the need for morality - we all exist in a dialogic moral space and must face questions of what kind of lives we want to live, "what it is good to be", in and through our relationships. Authenticity can never suffice here - we can only truly define our own identity in the context of those things that matter for us and others. Hence, moral identity is a mediator in the interplay between individual and society - by the same token, ethics is always about the boundaries of our individual freedom in service of the common good.

Finally, we will argue that an increasing fragmentation of morality and values leads directly to a vicious circle of increasing "wickedness" of our societal issues. As Alan Watkins suggests in "Wicked & Wise", most societal problems are inherently complex because they are SOCIAL problems, i.e. they depend on (ethical) judgment. A quick look at the Stacey matrix reminds us that complexity is directly related to the degree of disagreement in a society - hence, perversely, and we are simplifying here on purpose: the more "authentic" we all become, the more wicked our problems get, and the more we must invest in authenticity to cope with the increasing unpredictability of our lives. We can also look at the same phenomenon from the perspective of our capacity for societal transformation. As Stefano Zamagni reminds us, the neoliberal fantasy of freedom of choice is deeply flawed: we only ever have the freedom to choose from the options available - we can almost never determine what choices are available in the first place. This is exactly where the ability to engage interdependently, as individuals and organisations, in a wider societal blueprint "for good" becomes crucial. If we understand our self-development uniquely as individual adaptation and growing resilience to external changes, we are quickly commoditising ourselves as victim of circumstances, and lose our collective ability to improve society for everybody. Hence, we must beware of a modern desire for authenticity. It can quickly lead to a detachment from the community that holds us, and to the erosion of the moral character that can make us the best we can become. If we want to operationalise true purpose, we must nurture a relational identity, that embraces the committment to community and the moral prospect of a good society for all.

[Part 5] Eudaimocracy - Why Good Is the New Black

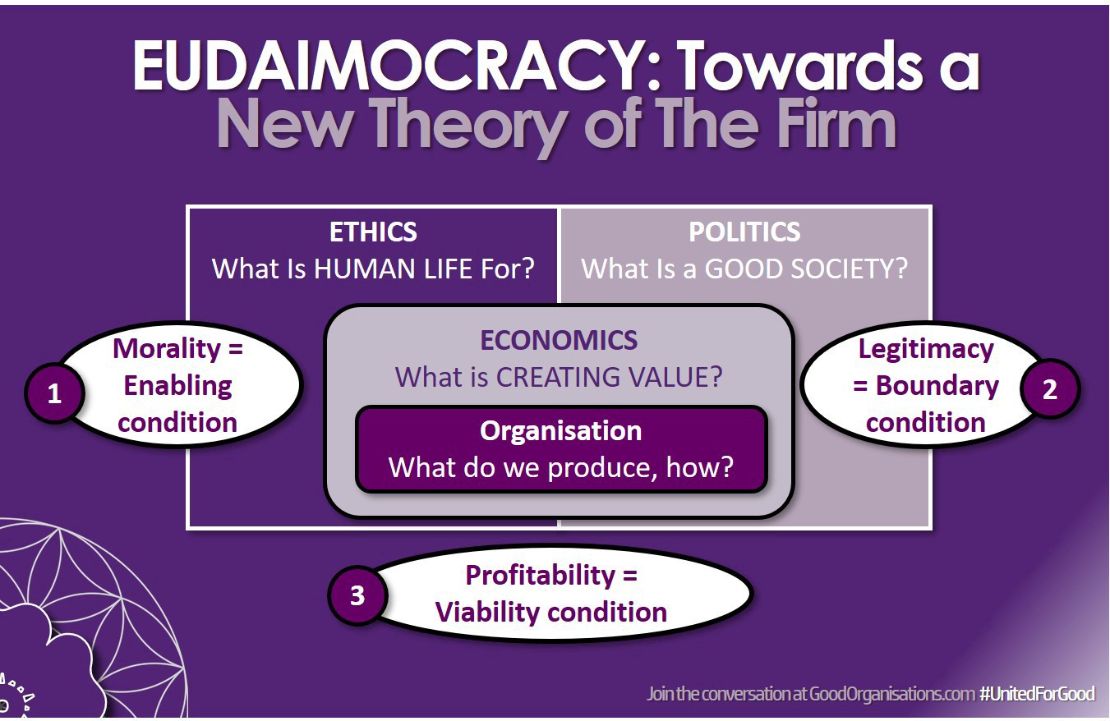

All of these reflections lead us directly to a larger and critical question: how can we define a new "theory of the firm" that appropriately reflects its societal embeddedness and injects ethics into the corporate DNA? How can we design truly purposeful, "good organisations" of the future? Whilst most people will agree that Ronald Coase's transaction costs theory, Jensen/Meckling's nexus of contracts or Williamson's theory of managerial utility maximization have largely run their course towards natural oblivion, it is less clear what comes next. Today's plethora of emergent organisational models is a mixed bag: from teal to humanocracy, Rendanheyi to adhocracy and sociocracy, b corps, PBCs and social enterprises - as well as endless variants of agile, platform or ecosystem businesses. It is easy to get lost. Moreover, most of these highly welcome innovations come without strong theoretical underpinnings, successful track record or explicit integration of (a clear and better) morality with management.

This is of course the very subject of our ongoing "Good Organisations" inquiry. Apropos, if any of this little essay has inspired you to explore new perspectives and if you are willing to go on a quest for collaborative learning, here is your invite you to join our little pilgrimage. Just leave your contact details on the www.goodorganisations.com website - we will arrange a first collective question-storming soon.

Whilst we do not have many answers yet, we are convinced that one change is essential - we need to enshrine a "higher purpose" explicitly in corporate governance. We propose that Organisations should become "for good". We have called it "Eudaimocracy": the rule of the good life for all.

What does that mean? Eudaimocratic organisations would seek to enable true "aliveness", at three levels: firstly, a) as actors in society. Businesses become "good" when they act honestly and take care of their ecosystem, jointly with other actors - beyond simply maximizing stakeholder utility, customer satisfaction, or shareholder profits. Secondly, b) the organization as a mini society, creates the container to enable mutual development of its members, within a wider community. By nurturing participation, trust, virtues and quality relationships, good organizations can "create" good people. And lastly, c) good organizations need to be trustees for the development of individuals, as they create opportunities to deploy talents and creativity, with pride and dignity in their organisational roles, whilst contributing collectively to a greater purpose.

And maybe you start to feel the difference: rather than balancing "purpose and profit", adding additional stakeholders to our annual reports, or ticking boxes in compliance sheets - good organisations enact their purpose by always putting the "good life" first - continuously adjusting themselves to serve the inclusive and sustainable prosperity of society at large, as their ultimate end.

Living Our True Purpose

Yet, whatever such organisations might eventually look like, one thing is certain: in order to truly grow up, they must be ready to accept that business has no separate morality and as leaders we cannot continue to remain morally mute. We must change our focus from what "I need" to what "I can do for Us". We must understand that purpose is not another objective, not an end state, but a process. Living and working "purpose-fully", day to day, means to act intentionally, accept shared responsibility and care for the whole, in every moment. Contrary to prominent management literature, excellence in business has never been just about what we achieve - it always was also about why and how we act. Through our acting, we embody and become the vision of who we are and who we want to be - as individuals, as businesses, as society, as humankind. It's far too easy to quickly update our purpose statements and simply continue as before…

Postscriptum: At some stage during the publication of our little essay, one of our kind readers thoughtfully objected: "thinking of purpose as something 'above and beyond' is poetics and not science"! We must strongly object to the claim that purpose should be science. In fact, we think that maybe our organisations should be more about poetry and less about science.

Throughout the centuries, the very idea of 'work' has transmuted from being an end in itself - as an expression of imago dei, in the glory of God (Benedictines' "ora et labora"); to becoming a path towards salvation (the Protestant work ethic); to degenerate into a means to an end (neoliberal capitalism). Slowly, human work and human beings became mere resources for the purpose of production. In the drama of human industry, science has often been both patron and henchman and is best kept away from normative questions. Science can only ever tell us what is (until proven wrong), but never what should be. That is the privilege of ethics. Like poetry, ethical inquiry is there for all of us to decipher the intrinsic symbolism of our life and work and to imagine what our future could be - who could we become? What can we hope for? May poetry prevail over science and re-enchant our work as a symbol of human joy - setting off that divine spark that is in all of us, binding together what consumerism, greed and cruelty have divided for far too long…

Ever singing, march we onward,

Victors in the midst of strife,

Joyful music leads us Sunward

In the triumph song of life…

All of these reflections lead us directly to a larger and critical question: how can we define a new "theory of the firm" that appropriately reflects its societal embeddedness and injects ethics into the corporate DNA? How can we design truly purposeful, "good organisations" of the future? Whilst most people will agree that Ronald Coase's transaction costs theory, Jensen/Meckling's nexus of contracts or Williamson's theory of managerial utility maximization have largely run their course towards natural oblivion, it is less clear what comes next. Today's plethora of emergent organisational models is a mixed bag: from teal to humanocracy, Rendanheyi to adhocracy and sociocracy, b corps, PBCs and social enterprises - as well as endless variants of agile, platform or ecosystem businesses. It is easy to get lost. Moreover, most of these highly welcome innovations come without strong theoretical underpinnings, successful track record or explicit integration of (a clear and better) morality with management.

This is of course the very subject of our ongoing "Good Organisations" inquiry. Apropos, if any of this little essay has inspired you to explore new perspectives and if you are willing to go on a quest for collaborative learning, here is your invite you to join our little pilgrimage. Just leave your contact details on the www.goodorganisations.com website - we will arrange a first collective question-storming soon.

Whilst we do not have many answers yet, we are convinced that one change is essential - we need to enshrine a "higher purpose" explicitly in corporate governance. We propose that Organisations should become "for good". We have called it "Eudaimocracy": the rule of the good life for all.

What does that mean? Eudaimocratic organisations would seek to enable true "aliveness", at three levels: firstly, a) as actors in society. Businesses become "good" when they act honestly and take care of their ecosystem, jointly with other actors - beyond simply maximizing stakeholder utility, customer satisfaction, or shareholder profits. Secondly, b) the organization as a mini society, creates the container to enable mutual development of its members, within a wider community. By nurturing participation, trust, virtues and quality relationships, good organizations can "create" good people. And lastly, c) good organizations need to be trustees for the development of individuals, as they create opportunities to deploy talents and creativity, with pride and dignity in their organisational roles, whilst contributing collectively to a greater purpose.

And maybe you start to feel the difference: rather than balancing "purpose and profit", adding additional stakeholders to our annual reports, or ticking boxes in compliance sheets - good organisations enact their purpose by always putting the "good life" first - continuously adjusting themselves to serve the inclusive and sustainable prosperity of society at large, as their ultimate end.

Living Our True Purpose

Yet, whatever such organisations might eventually look like, one thing is certain: in order to truly grow up, they must be ready to accept that business has no separate morality and as leaders we cannot continue to remain morally mute. We must change our focus from what "I need" to what "I can do for Us". We must understand that purpose is not another objective, not an end state, but a process. Living and working "purpose-fully", day to day, means to act intentionally, accept shared responsibility and care for the whole, in every moment. Contrary to prominent management literature, excellence in business has never been just about what we achieve - it always was also about why and how we act. Through our acting, we embody and become the vision of who we are and who we want to be - as individuals, as businesses, as society, as humankind. It's far too easy to quickly update our purpose statements and simply continue as before…

Postscriptum: At some stage during the publication of our little essay, one of our kind readers thoughtfully objected: "thinking of purpose as something 'above and beyond' is poetics and not science"! We must strongly object to the claim that purpose should be science. In fact, we think that maybe our organisations should be more about poetry and less about science.

Throughout the centuries, the very idea of 'work' has transmuted from being an end in itself - as an expression of imago dei, in the glory of God (Benedictines' "ora et labora"); to becoming a path towards salvation (the Protestant work ethic); to degenerate into a means to an end (neoliberal capitalism). Slowly, human work and human beings became mere resources for the purpose of production. In the drama of human industry, science has often been both patron and henchman and is best kept away from normative questions. Science can only ever tell us what is (until proven wrong), but never what should be. That is the privilege of ethics. Like poetry, ethical inquiry is there for all of us to decipher the intrinsic symbolism of our life and work and to imagine what our future could be - who could we become? What can we hope for? May poetry prevail over science and re-enchant our work as a symbol of human joy - setting off that divine spark that is in all of us, binding together what consumerism, greed and cruelty have divided for far too long…

Ever singing, march we onward,

Victors in the midst of strife,

Joyful music leads us Sunward

In the triumph song of life…

Popular articles in the KnowledgeHub: Good Society

.

.