Become a catalyst of good work and unite with others committed to making our organisations a little better!

differentiation

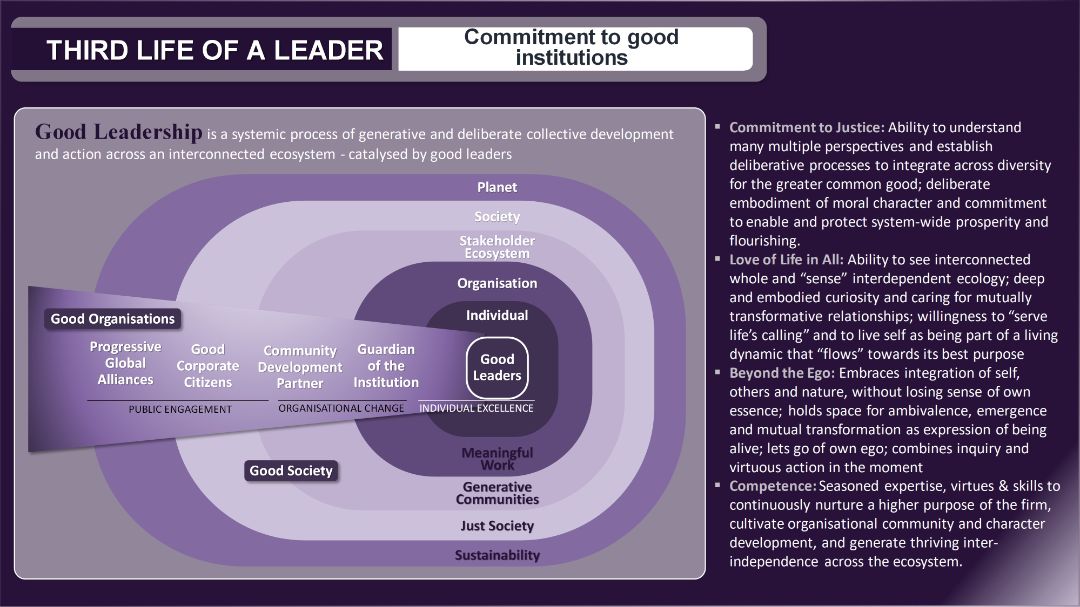

Letting Go of Leadership: The Urgent Case for A Global Leadership Iconoclasm

Before embarking on the journey, please read our piece about the need to connect personal and organisational transformation.

what makes a good leader? (Click on the icon)

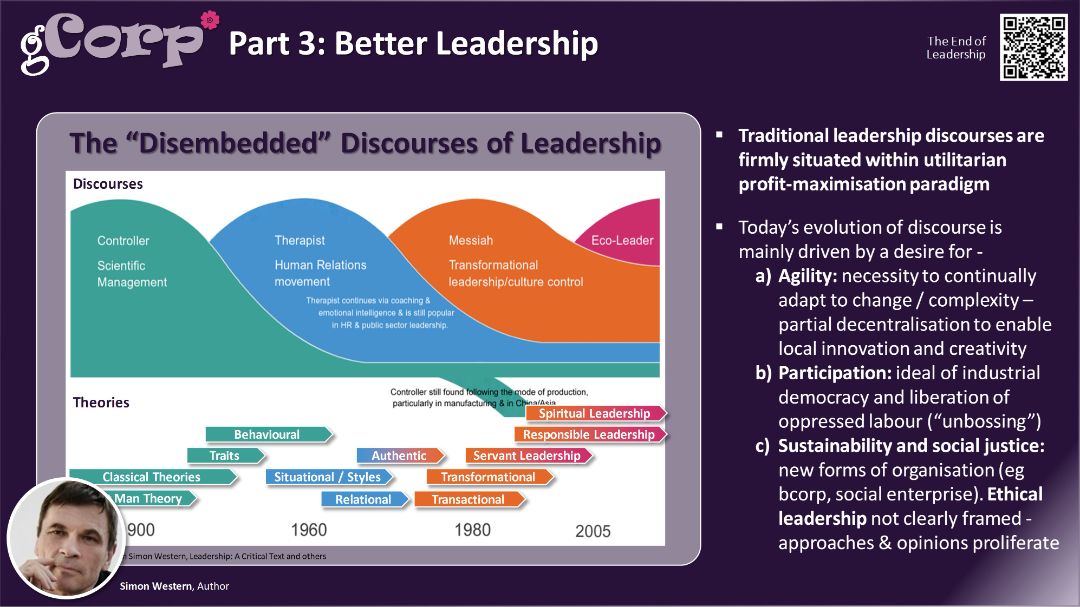

Are you a good leader? In case you are emphatically nodding, how would you know? Regrettably, it has become increasingly difficult to discern what "good Leadership" actually means. Searching Google reveals a mind-boggling 148 million links to the term. Amazon hosts over 100,000 entries. Every day, outfits like HBR broadcast ever-varying collections of "top" Leadership traits, behaviours and activities on social media. Such is the nature of the "Leadership industry" - entry barriers are low and armies of self-declared Leadership gurus incessantly bombard us with buzzwords galore.

Jump to

Finding the source of the transformation

Learning Journey

Core Concepts (click icons to jump to discovery)

How do organisations genuinely transform (for good)? (10)

What are the elements that play a key role in organizational transformation or development? How do organisations manage organisational change and transformation successfully?

What is the role of leadership in business transformation? (11)

What is leadership? What is the role of leaders in organisation? What is the overall contribution of leadership, and leaders, to organizational evolution? Consider how leadership behaviors, decisions, and strategies can influence the transformation process, positively and negatively.

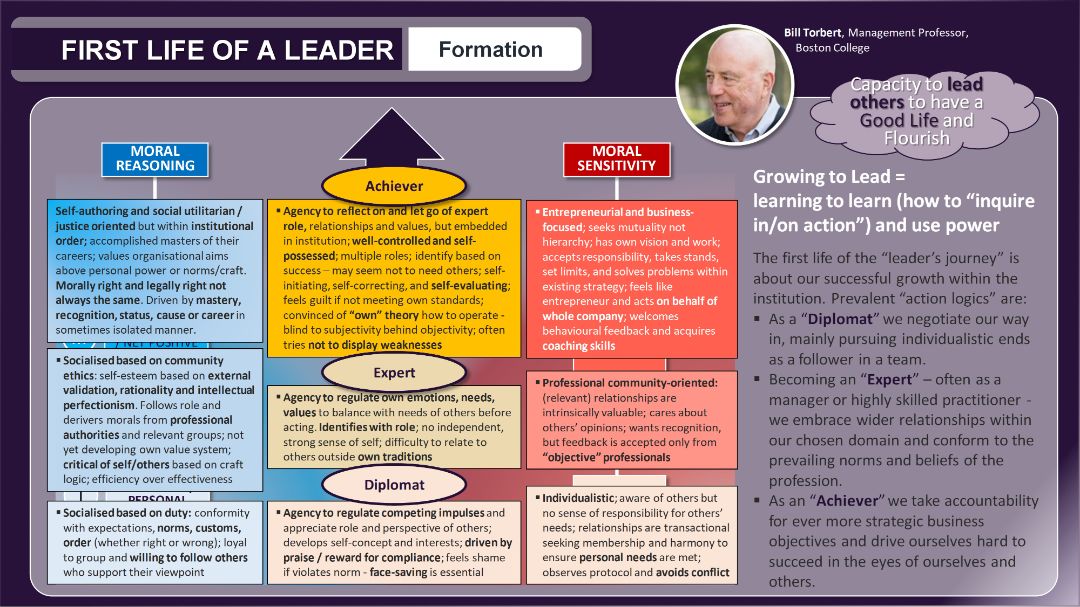

How can we develop good leaders? (12)

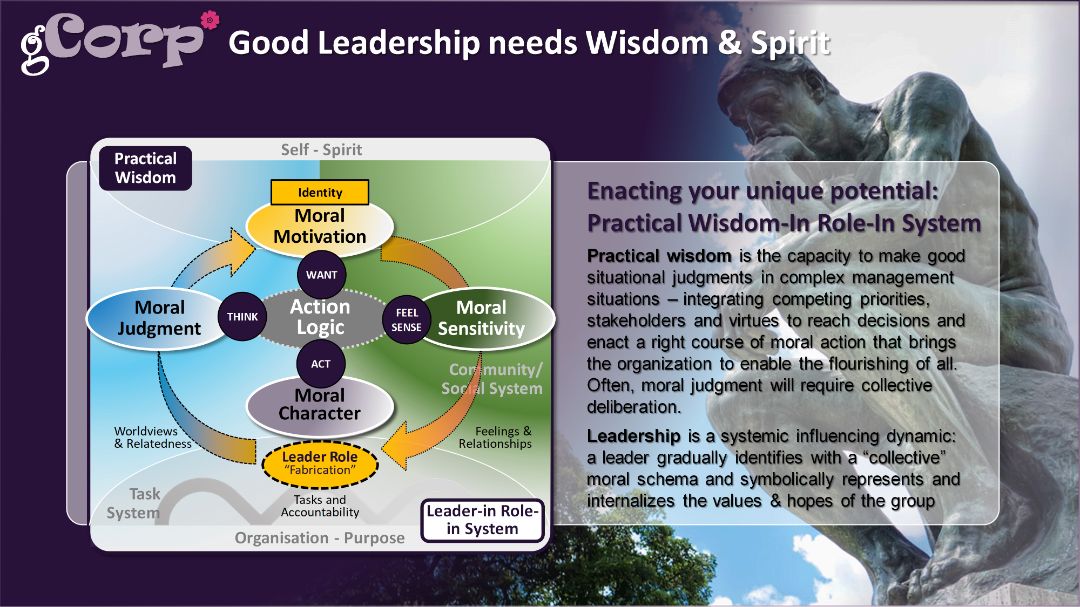

What does leadership development actually mean? And how does it work? What is the relevance of identity or "moral development" in leadership development? What is "practical wisdom"?

What is the "source" or spirit of transformation? How do leaders build, embody or amplify such a source?

Based on all of the above, note down in your journal some personal reflections. How do individual and organisational development interconnect, and is there a more essential “source” or spirit organisations and leaders can tap into for inspiration?

Our Perspective On Core Concepts

“An Ethical Business is one where people have learned to think and act for themselves – and come up with proper judgment of a situation. That requires an inner compass of what is right and wrong. When all people are on the same level of consciousness and understanding of what makes an action a ‘good action’ the business is ethical.” ― Alicia Hennig

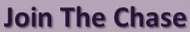

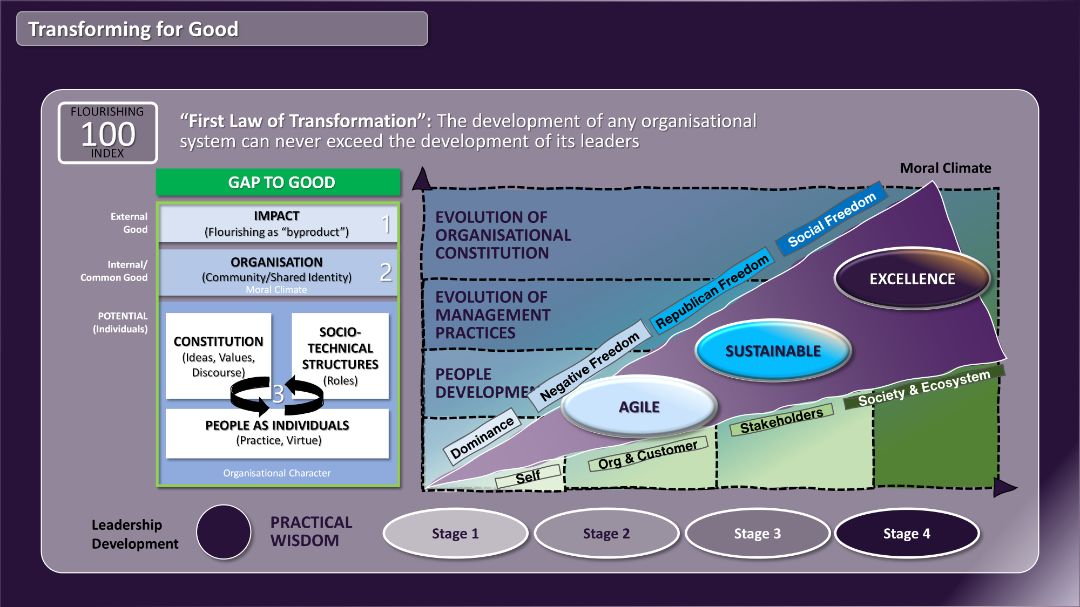

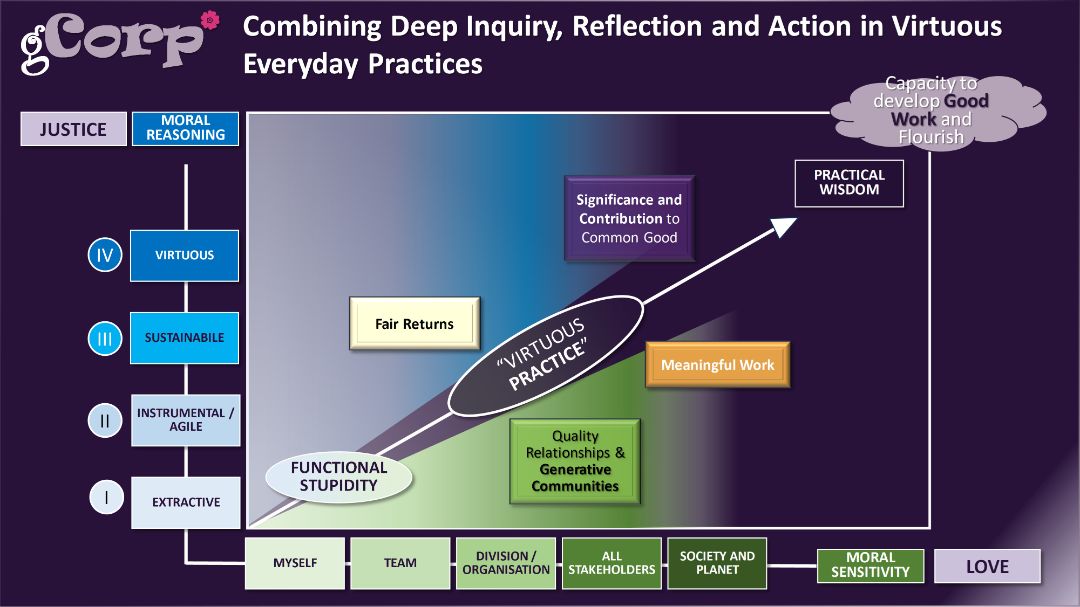

Transformation for Good: From Agile to Excellence

Our primary goal is to unravel the interplay between a) business transformation, b) leadership development, and c) the deeper sources that might drive both individual and organizational evolution.

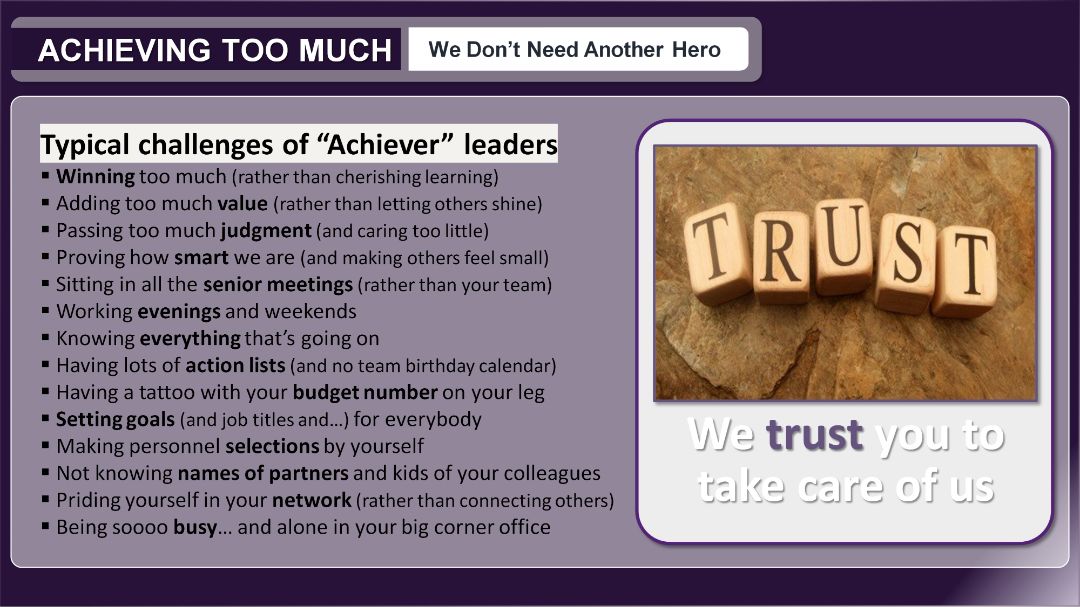

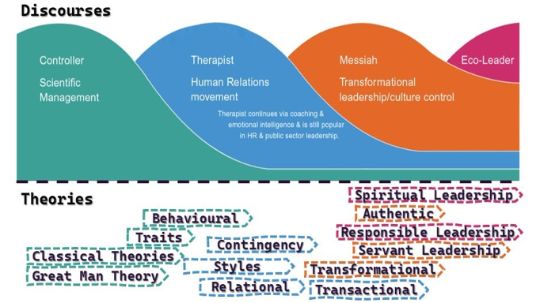

Therefore, we initially explore how a shift from "agility to excellence" is rooted in the purposeful reconfiguration of the organisational system, and observe how the organization's "moral climate" emerges over time. Then we delve into the critical role of leadership. We recognize the differences within contemporary leadership paradigms and theories, and establish the interconnection between systemic leadership cultivation, business transformation, and the development of individual leaders. Our hypothesis is that an organization's maturity can never exceed that of its leaders. Subsequently, we develop a leadership competency framework grounded in the concept of "practical wisdom" to examine the imperative for leaders to undergo personal transformation before they can become a force for good within their role. Finally, we seek to understand whether "good leadership" necessitates leaders to connect with and embrace a more transcendent and spiritual "source" within their organization, serving as the driving force and energy for perpetual development. Might that "source" enable or limit an organisation’s potential?

Below you will find, in a nutshell, the core concepts and hypotheses that drive the exploration:

Below you can also find a few blog posts that dive into our evolving thoughts around these concepts

Discover New Puzzle Pieces of Wisdom On A Search For Eureka Moments!

Materials marked in dark purple are foundational. Those flagged in light purple are for in-depth exploration.

Core Concept 10: Business Transformation (as a Shift in Collective Capacity)

“YOU DON'T “CREATE” A REGENERATIVE LIFE OR A REGENERATIVE BUSINESS. IT'S NOT AN END STATE. IT'S A PROCESS TO STAY CONSCIOUS AND WORK ON HOW WE LIVE IN WHAT WE CREATE” ― Carol Sanford

How do organisations transform (for good)?

What are the elements that play a key role in organizational transformation or development? How do organisations manage organisational change and transformation successfully?

Core Concept 11: Leadership (and Transformation)

What is the role of leadership in transformation?

- What is leadership? What is the role of leaders in organisation?

- What is the overall contribution of leadership, and leaders, to organizational evolution?

- Consider how leadership behaviors, decisions, and strategies can influence the transformation process, positively and negatively.

Core Concept 12: Leader Development and Practical Wisdom

How can we develop good leadership?

- What does leader(ship) development actually mean? And how does it work?

- What is the relevance of identity or "moral development" in leader(ship) development?

- What is "practical wisdom"?

Leadership: A Critical Text

Tribal Leadership: Leveraging Natural Groups to Build a Thriving Organization

The Leader on the Couch: A Clinical Approach to Changing People and Organizations

Metaphors We Lead By: Understanding Leadership in the Real World

Systems Leadership: Creating Positive Organisations

Images of Organization

Action Inquiry: The Secret of Timely and Transforming Leadership

Regenerative Leadership: The DNA of life-affirming 21st century organizations

The Business of Building a Better World: The Leadership Revolution That Is Changing Everything

Leadership BS: Fixing Workplaces and Careers One Truth at a Time

Cynefin - Weaving Sense-Making into the Fabric of Our World

The Empty Raincoat: Making Sense of the Future

Personality, Identity, and Character: Explorations in Moral Psychology

Virtuous Emotions

Leading Beyond the Ego: How to Become a Transpersonal Leader

Transpersonal Leadership in Action: How to Lead Beyond the Ego

The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do, and How to Change

Warriors for the Human Spirit

Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ

Influence, New and Expanded: The Psychology of Persuasion

The Power of Balance: Transforming Self, Society, and Scientific Inquiry

Leading Without Authority

Goddess Luminary Leadership Wheel: A Post-Patriarchal Paradigm

Agile Leadership Toolkit: Learning to Thrive with Self-Managing Teams

The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Leadership Fable

The Hero with a Thousand Faces

Understanding Organizations

Organizational Culture and Leadership

Spiral Dynamics: Mastering Values, Leadership and Change

Leading Change

The Lean Startup

Turn The Ship Around!: A True Story of Turning Followers into Leaders

The Different Drum: Community-making and peace

Appreciative Inquiry: A Positive Revolution in Change

Who Moved My Cheese: An Amazing Way to Deal with Change in Your Work and in Your Life

Blue Ocean Strategy

The Fifth Discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization

An Everyone Culture: Becoming a Deliberately Developmental Organization

The Stupidity Paradox: The Power and Pitfalls of Functional Stupidity at Work

The Oxford Handbook of Critical Management Studies

Radical Candor: How to Get What You Want by Saying What You Mean

Immunity to Change: How to Overcome It and Unlock the Potential in Yourself and Your Organization

Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World

Personal and Organizational Transformations: The True Challenge of Continual Quality Improvement

The Change Handbook: The Definitive Resource on Today's Best Methods for Engaging Whole Systems

Team Topologies: Organizing Business and Technology Teams for Fast Flow

Work with Source

Transcend: The New Science of Self-Actualization

.

.