Should the economy and businesses prioritize the betterment of society?

identification

Good Business Rankings: Little Fire, Lots of Smoke!

Before embarking on the journey, please read our piece about business rankings, awards and certificates to familiarise yourself with the challenge.

are business rankings (any) good? (Click on the icon for pdf)

Milton Friedman's one-goal dictate - Profit! - leads to growing "collateral damage". To this day, inhumane conditions are being toiled in countries of the global South to drive down costs in the supply chain. The Federal Environment Agency reports that about half of the companies in the German Stock Index do not sufficiently integrate the risks of climate change into their corporate strategy.Also, the pay of many workers still does not meet a minimum wage that enables cultural and social participation.

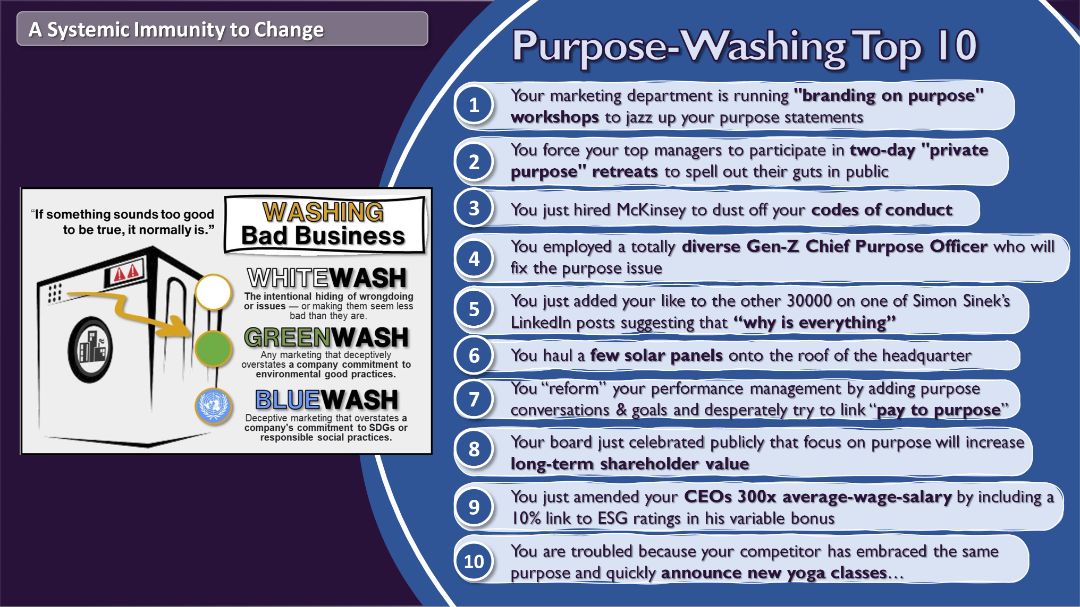

Thus, the call to rethink organisations is growing louder. Companies should be aware of their social responsibility and act accordingly. In the meantime, there are numerous rankings, awards and certificates that select socially responsible and "good" companies. However, this rating industry is confusing. Is all this merely window dressing and "good washing"? To find out, we have systematically analysed the rating approaches. The result: what "good" means from the perspective of the rating industry and how it is measured is unfortunately not always good.

Jump to

Why is the world better off because this organisation is in it?

Learning Journey

Core Concepts (click icons to jump to discovery)

The Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) Movement (4)

Critiques of capitalism and neoliberalism are not new. Why is business failing to address the problems?

Alternative Theories for a Responsible Economy (and Responsible Business) (5)

What defines a good economy, and what responsibilities should businesses have toward external stakeholders and society as a whole in such an economy?

What are the prerequisites for an organization to obtain a "license to operate"?

The Challenge to Measure Responsible Business (6)

What are the attempts to define and measure responsibility and sustainability? What are the problems with various existing frameworks?

What must business do more, better, and differently to become socially and ecologically responsible?

Based on all of the above, note down in your journal some personal reflections. What is your personal view? How will this shape your research to find responsible businesses?

Our Perspective On Core Concepts

"What really matters is that humans have no purpose. What we have is a role in an ecosystem. Being able to keep that ecosystem healthy means submitting ourselves to a whole life of being nested in a world that we affect and that affects us and our ability to play our role - not to figure out what we want." ― Carol Sanford

Businesses must become responsible

In our journey to understand the complexities of contemporary capitalism, one glaring truth emerges: businesses wield immense influence over the fabric of society. Contrary to the arguments of some (classical) economic theorists, the economy's legitimacy cannot be divorced from its social impact. As we confront the pressing challenges of our time, it becomes increasingly clear that businesses must shoulder their share of responsibility in fostering a just and prosperous society. This realization forms the bedrock of our inquiry: How can businesses leverage their power and resources to contribute positively to the well-being of communities and individuals, and the betterment of society?

Click on each concept heading to learn more...

Below you can also find a few blog posts that dive into our evolving thoughts around these concepts

““Efficiency turns out to mean measurable efficiency. Efficiency comes down to what you can measure and exploit. You can't measure love. You can't measure communityship. But, yeah, you can measure profit.” .” ― Henry Mintzberg

Discover New Puzzle Pieces of Wisdom On A Search For Eureka Moments!

Materials marked in dark purple are foundational. Those flagged in light purple are for in-depth exploration.

Core Concept 4: Corporate Social Responsibility

Core Concept 4: Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR)

Please reflect for yourself: Critiques of capitalism and neoliberalism are not new. What is CSR all about and why is business failing to address the problems?1) What is CSR (and Corporate Sustainability)?

2) What are the reasons why CSR is not working?

3) Can CSR work within a Capitalistic system?

Core Concept 5: Alternative Theories for a Responsible Economy (& Responsible Business)

Core Concept 5: Alternative Theories for a Good Economy (and Responsible Business)

Please reflect: What are the most important theories that seek to improve Capitalism? How is a responsible business defined by these different models? What responsibilities should businesses have toward external stakeholders and society as a whole?

1) What are the alternative theories and models for corporate responsibility?

2) What is the role of responsible business in each of these alternatives?

3) What are the strengths and weaknesses of these models?

Core Concept 6: The Challenge to Measure Responsible Business

Core Concept 6: The Challenge to Measure Responsible Business

Please reflect: What are the attempts to define and measure responsibility and sustainability? What are the problems with various existing frameworks?

1) How is social and economic impact of business measured? What are the better known measures and evaluative concepts?

2) What lessons can we learn from the frameworks Triple Bottom Line, ESG or B-Corps?

3) On that basis, how can we design a better way to qualify and select good organizations?

The Future of the Commons: Beyond Market Failure & Government Regulations

A Circular Economy Handbook: How to Build a More Resilient, Competitive and Sustainable Business

Conscious Capitalism, With a New Preface by the Authors: Liberating the Heroic Spirit of Business

Stakeholder Capitalism: A Global Economy that Works for Progress, People and Planet

The Stiglitz Report: Reforming the International Monetary and Financial Systems in the Wake of the Global Crisis

The Integrated Reporting Movement: Meaning, Momentum, Motives, and Materiality

The Triple Bottom Line

The End Of Corporate Social Responsibility

PROSPERITY ECONOMICS

DEGROWTH ECONOMICS

DOUGNHUT ECONOMICS

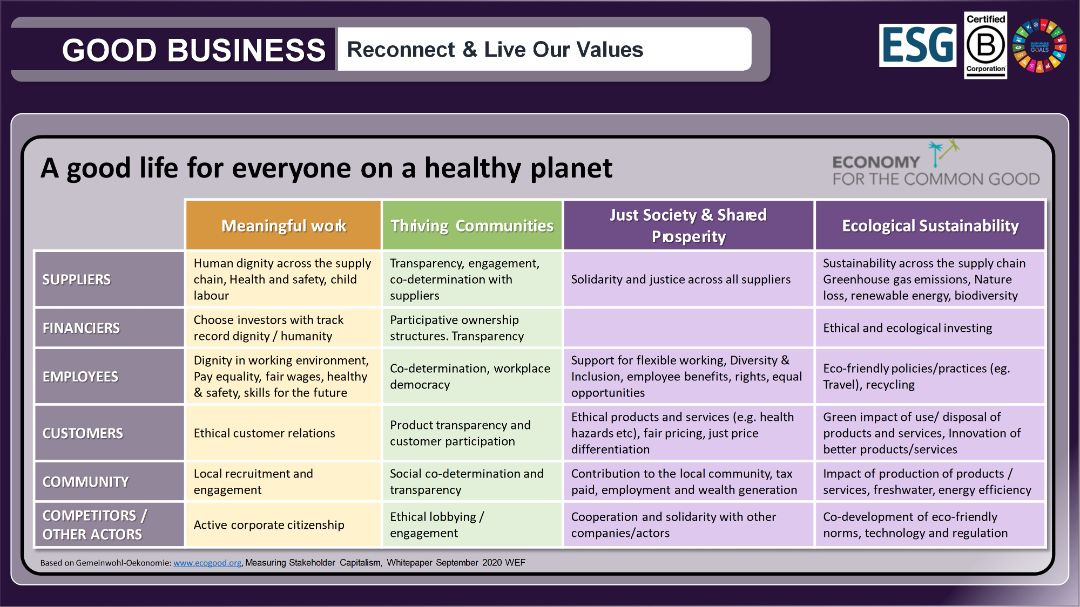

ECONOMY FOR THE COMMON GOOD

SOLIDARITY ECONOMY

LIVING EARTH ECONOMY

wellbeing economics

.

.