Rankings, awards, certificates - there are numerous employer labels that distinguish companies as good employers. But much of it is "good washing", as an analysis by the Research Institute for Work and Working Environments at the University of St. Gallen shows.

There is a shortage of skilled workers! A situation that many human resources managers are painfully aware of. The reasons for this are manifold and have to do with demographic change, among other things. But the "shortage situation" is often also home-made: blind actionism, work intensification, and pressure due to competition between employees can create a toxic working climate. The result: demotivation, illness, or the "quiet quitting" (working to rule) often lamented these days.

Milton Friedman's one-goal dictate - Profit! - leads to growing "collateral damage". To this day, inhumane conditions are being toiled in countries of the global South to drive down costs in the supply chain. The Federal Environment Agency reports that about half of the companies in the German Stock Index do not sufficiently integrate the risks of climate change into their corporate strategy

Also, the pay of many workers still does not meet a minimum wage that enables cultural and social participation.

Thus, the call to rethink organisations is growing louder. Companies should be aware of their social responsibility and act accordingly. In the meantime, there are numerous rankings, awards and certificates that select socially responsible and "good" companies. However, this rating industry is confusing. Is all this merely window dressing and "good washing"? To find out, we have systematically analysed the rating approaches. The result: what "good" means from the perspective of the rating industry and how it is measured is unfortunately not always good.

The rating industry under the microscope: Overview of evaluation quality

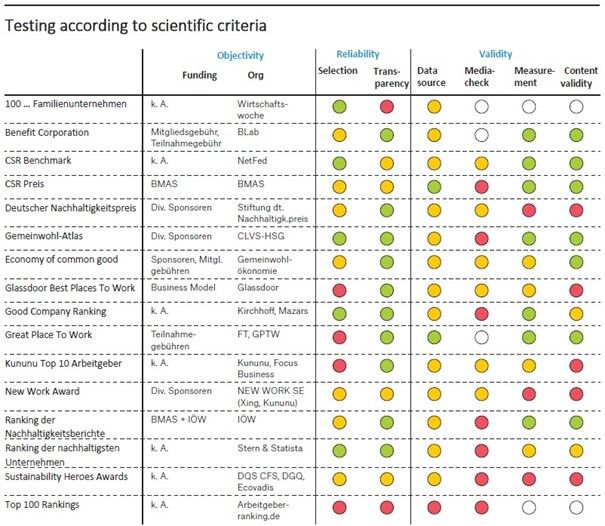

The first step of our analysis included an extensive internet search using search terms such as "rankings", "awards", and "certificates" in connection with "corporate social responsibility", "ethics", and "sustainability". We tracked down further providers through expert interviews. We considered all initiatives that publicly communicate the results of their evaluation process. We weeded out those who were primarily using the awards for their acquisition. Thus, we identified 16 valuation approaches (see figure “Testing according to scientific criteria”).

There is a shortage of skilled workers! A situation that many human resources managers are painfully aware of. The reasons for this are manifold and have to do with demographic change, among other things. But the "shortage situation" is often also home-made: blind actionism, work intensification, and pressure due to competition between employees can create a toxic working climate. The result: demotivation, illness, or the "quiet quitting" (working to rule) often lamented these days.

Milton Friedman's one-goal dictate - Profit! - leads to growing "collateral damage". To this day, inhumane conditions are being toiled in countries of the global South to drive down costs in the supply chain. The Federal Environment Agency reports that about half of the companies in the German Stock Index do not sufficiently integrate the risks of climate change into their corporate strategy

Also, the pay of many workers still does not meet a minimum wage that enables cultural and social participation.

Thus, the call to rethink organisations is growing louder. Companies should be aware of their social responsibility and act accordingly. In the meantime, there are numerous rankings, awards and certificates that select socially responsible and "good" companies. However, this rating industry is confusing. Is all this merely window dressing and "good washing"? To find out, we have systematically analysed the rating approaches. The result: what "good" means from the perspective of the rating industry and how it is measured is unfortunately not always good.

The rating industry under the microscope: Overview of evaluation quality

The first step of our analysis included an extensive internet search using search terms such as "rankings", "awards", and "certificates" in connection with "corporate social responsibility", "ethics", and "sustainability". We tracked down further providers through expert interviews. We considered all initiatives that publicly communicate the results of their evaluation process. We weeded out those who were primarily using the awards for their acquisition. Thus, we identified 16 valuation approaches (see figure “Testing according to scientific criteria”).

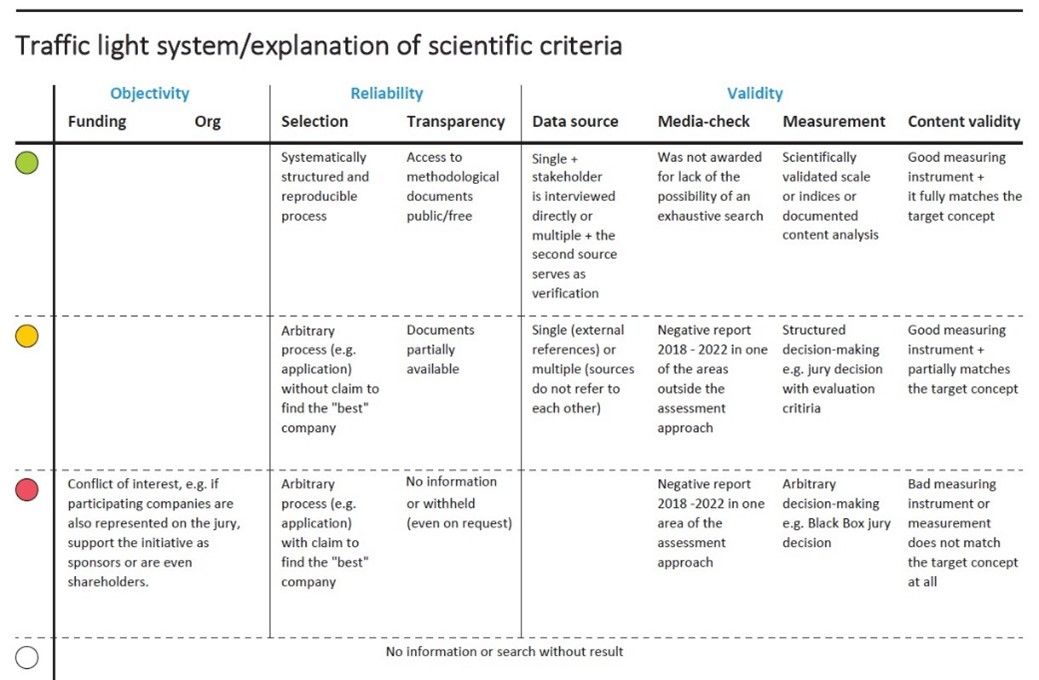

In a second step, we recorded the respective definition of a good company and the methodology applied. Finally, we critically examined the methodology in terms of objectivity, reliability and validity. We developed a traffic light system that indicates the scientific quality of the assessment approaches (see figure above).

The result clearly shows that no approach stands up to all scientific criteria. Nevertheless, we recognise efforts to find good companies with suitable methods. We cannot recommend the following five approaches, as they only achieve a satisfactory rating in one or even none of the criteria: the 100 most innovative and sustainable family businesses, the German Sustainability Award, the New Work Award, Sustainability Heroes and Top 100 Rankings. Three aspects seem to be particularly problematic from an evidence-based assessment perspective: Firstly, the comparison with media coverage during the period of the award showed that the companies in the assessed area were doubted, which suggests rifts between appearance and reality. In addition, some of the decisions were highly subjective. The New Work Award, Sustainability Heroes and the German Sustainability Award, among others, rely on a jury decision without a comprehensible catalogue of criteria.

This does not have to be bad, but it falls short of the objective evaluation procedures of other approaches. Overall, transparency did not always meet expectations either. For example, the methodology of the Top 100 rankings and the 100 most innovative and sustainable family businesses remained a black box for us (the information was not available even when asked).

Aspiration and reality diverge

The analysis also reveals that the claims in the assessment approaches are sometimes better, sometimes worse implemented. The inconsistencies with regard to content validity (i.e. whether what is measured is what is claimed to be measured) were striking.

Both Kununu and Glassdoor want to use their rankings to recognise the best employers from the employees' point of view. However, they do not carry out a measurement according to scientific standards. In order to be able to make a real statement about the quality of the company for employees, it is necessary to have an elaborate questionnaire such as the one used by Great Place to Work. In addition, a - at least rudimentarily - representative sample is required.

Other approaches go beyond the needs of employees in their demand for a good company and pursue a broader concept of goals. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is often at the centre of this. The corresponding measurement tools must be able to cover more than just the relationship between employer and employee.

In a second step, we recorded the respective definition of a good company and the methodology applied. Finally, we critically examined the methodology in terms of objectivity, reliability and validity. We developed a traffic light system that indicates the scientific quality of the assessment approaches (see figure above).

The result clearly shows that no approach stands up to all scientific criteria. Nevertheless, we recognise efforts to find good companies with suitable methods. We cannot recommend the following five approaches, as they only achieve a satisfactory rating in one or even none of the criteria: the 100 most innovative and sustainable family businesses, the German Sustainability Award, the New Work Award, Sustainability Heroes and Top 100 Rankings. Three aspects seem to be particularly problematic from an evidence-based assessment perspective: Firstly, the comparison with media coverage during the period of the award showed that the companies in the assessed area were doubted, which suggests rifts between appearance and reality. In addition, some of the decisions were highly subjective. The New Work Award, Sustainability Heroes and the German Sustainability Award, among others, rely on a jury decision without a comprehensible catalogue of criteria.

This does not have to be bad, but it falls short of the objective evaluation procedures of other approaches. Overall, transparency did not always meet expectations either. For example, the methodology of the Top 100 rankings and the 100 most innovative and sustainable family businesses remained a black box for us (the information was not available even when asked).

Aspiration and reality diverge

The analysis also reveals that the claims in the assessment approaches are sometimes better, sometimes worse implemented. The inconsistencies with regard to content validity (i.e. whether what is measured is what is claimed to be measured) were striking.

Both Kununu and Glassdoor want to use their rankings to recognise the best employers from the employees' point of view. However, they do not carry out a measurement according to scientific standards. In order to be able to make a real statement about the quality of the company for employees, it is necessary to have an elaborate questionnaire such as the one used by Great Place to Work. In addition, a - at least rudimentarily - representative sample is required.

Other approaches go beyond the needs of employees in their demand for a good company and pursue a broader concept of goals. Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is often at the centre of this. The corresponding measurement tools must be able to cover more than just the relationship between employer and employee.

This challenge has not always been fully met. For example, the ranking of the most sustainable companies in Germany measures the environmental sub-area in a convincing manner with corresponding key figures but has weaknesses in the measurement of the social area. A similar problem occurs in the Good Company Ranking. In the categories Society, Employees, Environment and Financial Integrity, it measures the last two categories validly. Instead of social responsibility, however, only the image of the company is tested. There is "room for improvement".

Many assessment approaches are thematically fragmented. Apart from the examples described, the results are also of limited content validity due to social desirability effects and lack of control of self- statements. But this is precisely what the quality and credibility of an assessment approach ultimately depend on.

Good towards whom? - The circle of responsibility

A good company assessment approach should integrate the concerns of key stakeholders. In our analysis, we identified several aspects that are essential for a holistic assessment: employee- oriented corporate policies that focus on the individual as well as the whole community, the careful use of natural resources/active protection of nature and climate, social commitment as responsibility for the communities, a responsible supply chain, appreciative customer relationships, and the contribution to a culture of cooperation, respect and open source innovation among competitors.

Our analysis showed that not even half of all initiatives do justice to the stakeholder spectrum with their approach. The majority address impacts on only one stakeholder. Some approaches, such as Great Place to Work, have a strong focus on employees and capture this area with an adequate measurement tool. However, this perspective alone is too narrow, as there are significant interactions between the stakeholder groups. The same can be seen in the CSR Benchmark assessment approach. The stated goal is to rank companies based on their digital sustainability communication. There are no fundamental criticisms of the measuring instrument and the content validity. Nevertheless, the approach is not suitable for identifying good organisations. As important as communication and transparency are for customers and other stakeholders, companies must be measured by the impact they have on their corporate environment. Modern and transparent communication cannot improve the common good as long as there are only negative things to communicate. The Common Good Atlas is a content-valid measurement. It is characterised by a unique public value perspective based on four basic human needs but lacks a view of the impact on the individual stakeholders.

This challenge has not always been fully met. For example, the ranking of the most sustainable companies in Germany measures the environmental sub-area in a convincing manner with corresponding key figures but has weaknesses in the measurement of the social area. A similar problem occurs in the Good Company Ranking. In the categories Society, Employees, Environment and Financial Integrity, it measures the last two categories validly. Instead of social responsibility, however, only the image of the company is tested. There is "room for improvement".

Many assessment approaches are thematically fragmented. Apart from the examples described, the results are also of limited content validity due to social desirability effects and lack of control of self- statements. But this is precisely what the quality and credibility of an assessment approach ultimately depend on.

Good towards whom? - The circle of responsibility

A good company assessment approach should integrate the concerns of key stakeholders. In our analysis, we identified several aspects that are essential for a holistic assessment: employee- oriented corporate policies that focus on the individual as well as the whole community, the careful use of natural resources/active protection of nature and climate, social commitment as responsibility for the communities, a responsible supply chain, appreciative customer relationships, and the contribution to a culture of cooperation, respect and open source innovation among competitors.

Our analysis showed that not even half of all initiatives do justice to the stakeholder spectrum with their approach. The majority address impacts on only one stakeholder. Some approaches, such as Great Place to Work, have a strong focus on employees and capture this area with an adequate measurement tool. However, this perspective alone is too narrow, as there are significant interactions between the stakeholder groups. The same can be seen in the CSR Benchmark assessment approach. The stated goal is to rank companies based on their digital sustainability communication. There are no fundamental criticisms of the measuring instrument and the content validity. Nevertheless, the approach is not suitable for identifying good organisations. As important as communication and transparency are for customers and other stakeholders, companies must be measured by the impact they have on their corporate environment. Modern and transparent communication cannot improve the common good as long as there are only negative things to communicate. The Common Good Atlas is a content-valid measurement. It is characterised by a unique public value perspective based on four basic human needs but lacks a view of the impact on the individual stakeholders.

The demand for good: meeting standards or "becoming better and better"

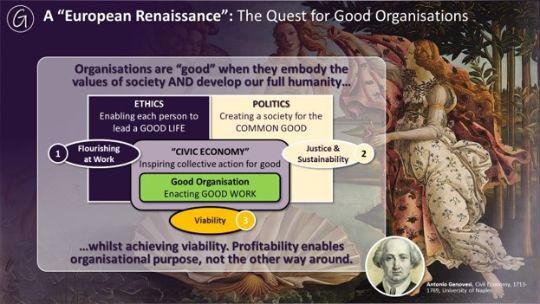

Workers and other stakeholders today have higher expectations of a company that is labelled as good. These perceptions go far beyond Friedman's profit mantra. Organisations are also expected to meet ethical standards.

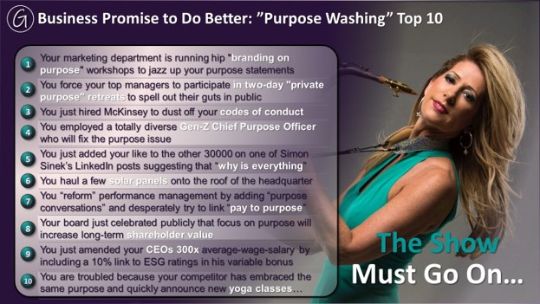

The first thing that comes to mind is standards such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), to which more and more companies are committing. In the assessment industry, compliance with human rights in the supply chain is also often rewarded with a higher score. This rules-based view of good practices may reduce suffering and thus contribute to better social performance. But it often ignores that "good" is more than the absence of "bad". "Good" companies should go beyond minimum requirements. It is not enough to work through lists or collect certificates. Rather, employers should have a genuine interest in their constant development and continually look for the "good".

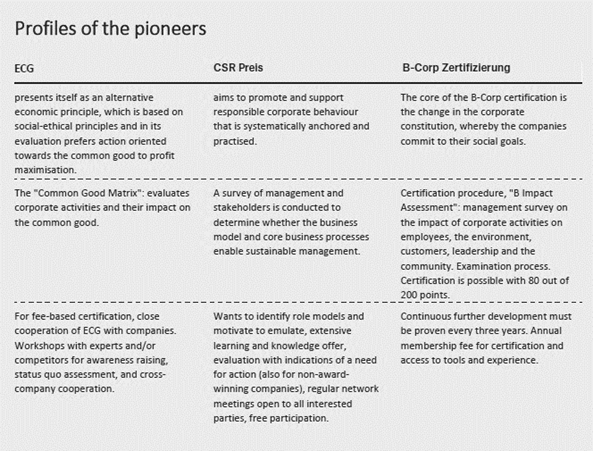

Such goals are not easy to realise and their achievement is even more difficult to measure. But some awards are trying and, in our view, can be considered pioneers. The Economy of common good (ECG), the CSR Award, Benefit Corporation (B Corp) and the ranking of sustainability reports are convincing not only because of their measurement quality but also because of the broad inclusion of all social actors who are in contact with the companies.

The first three additionally emphasise the continuous development of the companies - better in the sense of good. We have portrayed these three approaches in the table above.

The way of the future - a development towards Good

“Good companies should go beyond minimum requirements. It is not always enough to work through lists and collect certificates. Rather, employers should have a genuine interest in the development and always look for the good.”

To be truly good, it takes more than what most of the approaches discussed here offer. Even though we have discovered some recommendable assessment procedures, the motto "good is not good enough" still applies - not in a perfectionist sense, but in the sense of the Aristotelian virtue ethics. For people, life is about achieving the highest possible potential and leading a good and happy life. And organisations should use their resources to support this endeavour.

The evaluation approaches discussed here usually point very timidly, in three cases already somewhat more courageously, in the right direction. Anyone seriously interested in showing the company new perspectives can enter into an intensive learning process via the approaches highlighted. This would be the beginning of a better life for everyone involved in an organisation. More thinking together and with each other in the company (and hopefully also in the stakeholder network) should be the reward for the new path taken.

Originally published by Haufe, Strategy & Leadership. Article by Silvio Christoffel, Thao Quynh Phi and Antoinette Weibel.

The demand for good: meeting standards or "becoming better and better"

Workers and other stakeholders today have higher expectations of a company that is labelled as good. These perceptions go far beyond Friedman's profit mantra. Organisations are also expected to meet ethical standards.

The first thing that comes to mind is standards such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), to which more and more companies are committing. In the assessment industry, compliance with human rights in the supply chain is also often rewarded with a higher score. This rules-based view of good practices may reduce suffering and thus contribute to better social performance. But it often ignores that "good" is more than the absence of "bad". "Good" companies should go beyond minimum requirements. It is not enough to work through lists or collect certificates. Rather, employers should have a genuine interest in their constant development and continually look for the "good".

Such goals are not easy to realise and their achievement is even more difficult to measure. But some awards are trying and, in our view, can be considered pioneers. The Economy of common good (ECG), the CSR Award, Benefit Corporation (B Corp) and the ranking of sustainability reports are convincing not only because of their measurement quality but also because of the broad inclusion of all social actors who are in contact with the companies.

The first three additionally emphasise the continuous development of the companies - better in the sense of good. We have portrayed these three approaches in the table above.

The way of the future - a development towards Good

“Good companies should go beyond minimum requirements. It is not always enough to work through lists and collect certificates. Rather, employers should have a genuine interest in the development and always look for the good.”

To be truly good, it takes more than what most of the approaches discussed here offer. Even though we have discovered some recommendable assessment procedures, the motto "good is not good enough" still applies - not in a perfectionist sense, but in the sense of the Aristotelian virtue ethics. For people, life is about achieving the highest possible potential and leading a good and happy life. And organisations should use their resources to support this endeavour.

The evaluation approaches discussed here usually point very timidly, in three cases already somewhat more courageously, in the right direction. Anyone seriously interested in showing the company new perspectives can enter into an intensive learning process via the approaches highlighted. This would be the beginning of a better life for everyone involved in an organisation. More thinking together and with each other in the company (and hopefully also in the stakeholder network) should be the reward for the new path taken.

Originally published by Haufe, Strategy & Leadership. Article by Silvio Christoffel, Thao Quynh Phi and Antoinette Weibel.

Other popular articles in the KnowledgeHub: Good Economy

.

.