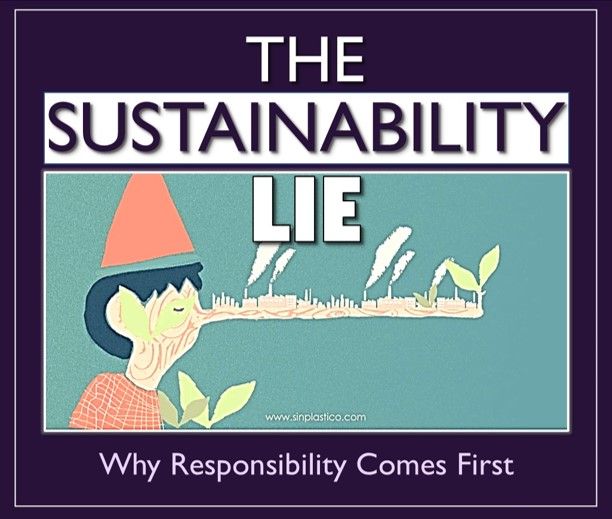

I will argue that this is no surprise: the concept of sustainability is flawed and often fashionable for all the wrong reasons — in order to make progress, we must revert to a more fundamental question of corporate responsibility and ethics.

But first things first: what is sustainability all about? Essentially, corporate sustainability advocates long-term thinking in respect to the environment, the next generation/s and our planet. The main idea behind sustainability is to have “as little negative impact as possible”. Sounds great, but it immediately opens up a number of problems:

- Firstly, there is no single definition of what “long term” actually means. Often terms are chosen by convenience, arbitrarily (“next generation”), or based on scientific, yet highly uncertain statistics (e.g., the Paris agreement seeks to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees, and estimates suggest it requires cutting emissions by 50% by 2030).

- Secondly, sustainability is pragmatically accommodated within our existing instrumentally-rational economic paradigm. In other words, corporate decisions are based on financial business cases that seek to maximise profits (in terms of ROI, IRR, NPV of projected cash flows etc). In order to make them more “sustainable”, we extend the temporal horizon when comparing costs and benefits of our actions, whilst (voluntarily) accommodating some “environmental risks”, or offsetting environmental costs. Rather than being profitable next quarter, or within the duration of a current political mandate, we seek to be both profitable and “net positive”, i.e., “have as little impact as possible”, in the long run — let’s say the next 20–50 years. Of course, any such (utilitarian) calculus comes with the usual challenges of translating “externalities” and common goods into monetary terms — for example, by applying VSL (value of a statistical life) calculations to assess the “cost” — sorry I meant: value — of a human life, or by „capitalising nature“ to estimate “residual values” for environmental damage. Moreover, there is no real consensus over what ‘as little impact as possible’ really means and which specific risks are to be considered how — in most cases, we simply add (pretty cheap) SDG projects to annual reports, upgrade (pretty expensive) marketing materials and take cute (and super cheap!) selfies with smiling school children next to our factory in Africa. Whilst we are thus busily trying to turn sustainability into yet another sales opportunity, competitive advantage or greenwashing — we conveniently confuse the world with an industry of new accounting and communication practices (think ESG!). And in the meantime, we continue happily as before: treating life as our — well, almost — unlimited resource and refusing to more fundamentally question the purpose of organisations in a societal and natural ecosystem.

- Thirdly, even when people earnestly try to take a more principled approach to sustainability, opinions as to what exactly that implies and how it could be measured vary widely. Suggesting the need to become “good ancestors”, “treat nature like a person”, or “do good by our children”, people mostly argue for more regulation and stricter limits to economic growth, beyond just voluntary action. Proposals range from doughnut economics and “do no harm” regulations to international treaties to reduce CO2 emissions. But, firstly, any such calls to action are normally thwarted by solemn reminders of politicians that we are all impotent victims of globalised markets. Secondly, a deontic approach — be it based on bioegalitarianism, deep ecology or scientific damage forecasts — often fails to propagate goodness; as we know from much research, compliance codes quickly erode any natural predisposition of actors to behave ethically. Thirdly, the expedient fuzziness of the concept makes it impossible to derive consistent and effective legislation; suggested legal limits are mostly arbitrary and only represent minimum consensus, rather than contingent optimums. Yet, maybe even more importantly, much of the vocal activism remains focused on external damage regulation — rather than the development of inner consciousness and better educational and institutional practices. Collectively, we often fail to reflect more deeply about what it really means — in terms of our own behaviours — to live a good life, and to collectively craft good organisations and a good economy. As Ed Freeman once said: there is a big difference between “doing right” and doing good.

This leads me to the essential difference between sustainability and responsibility: as per above, sustainability is about maintaining a specific parameter at a certain rate or level — it focuses on the task and its outcomes; thus, corporate sustainability seeks to maintain a specific level of social or environmental well-being (or damage) in the future. Its typical image is some version of a Venn diagram, representing a triple (or quadruple) bottom line. Conversely, responsibility is the state of being accountable — it focuses on the character of the actor and their principles. Corporate responsibility, therefore, reflects on the fundamental accountability of business to contribute to society, through all its activities, and accepts an existential obligation to take care of society and planet, and their needs. It thus refers to inner standards, based on an objective duty towards humanity, justice and ethical norms (think Adam Smith’s impartial spectator who represents “the eyes of mankind”). It’s typical image is a diagram of concentrical circles, with an all-integrative ideal of the “good life” at its core, upon which society is founded, and which the economy sustains.

Of course, sustainability and responsibility overlap and can combine — as Ricardo Torelli suggests: “being sustainable and taking care of your present and your future by not exploiting resources more than there are, easily translates into responsible behaviour, in which you are taking care of someone/something according to their problems and needs”. In other words, it is of course possible to both act in a principled fashion (stopping pollution now if it is ethically wrong), and to take a long-term and multi-stakeholder perspective on consequences (e.g., by ensuring appropriate measures to mitigate negative implications or optimise outcomes from responsible action). However, this is often not what happens in business. As a matter of fact, sustainability is often claimed without fundamentally changing the way we work. For example, when a company in the oil & gas sector “offsets” dangerous emissions by acquiring carbon credits, or by installing photovoltaic systems on the roof of all its premises. Or when Qatar claims to run a “sustainable” world cup by installing greenery in all stadiums and build a few wind turbines. Or when you and I continue to use corporate travel, but pay a few dollars to “make the travel green”.

Essentially, sustainability does not necessarily imply, demand or enhance ethical responsibility. It therefore can incentive a marginal and superficial — if not fraudulent — logic for action. By the same token, it is conveniently argued that the limits to growth can be changed towards a new paradigm “to grow the limits” – we don’t need to produce less, but simply require more technology and innovation to help us “grow the pie”! Thus, our modern economic emperors proudly sport sustainable new clothes, and continue to advocate paracetamol against cancer. That’s why it is no surprise that younger generations increasingly question the credibility of corporate and political actors. And, sadly, the UN’s SDGs, with all its laudable effort to mitigate environmental degradation, might unwittingly (?) contribute to the survival of exactly the type of economic system which causes the damage it seeks to reduce in the first place. Sustainability becomes a hegemonic societal discourse that, above all, ‘sustains’ the powers and structures that are already there.

In conclusion, the truth is pretty simple: we all might feel good about ourselves by advocating sustainability and long-termism, but if we really want to build a better system, we must seek to understand what makes our societal system worthy of being sustained in the first place. We must be willing to take personal care of the world and of each other; we must agree and enact mutual ethical responsibility; and we must accept that it will come with personal and collective sacrifices, commitment and costs. Because if something is wrong, it’s wrong — however sophisticated our attempts to make it look sustainable might be.

I will argue that this is no surprise: the concept of sustainability is flawed and often fashionable for all the wrong reasons — in order to make progress, we must revert to a more fundamental question of corporate responsibility and ethics.

But first things first: what is sustainability all about? Essentially, corporate sustainability advocates long-term thinking in respect to the environment, the next generation/s and our planet. The main idea behind sustainability is to have “as little negative impact as possible”. Sounds great, but it immediately opens up a number of problems:

- Firstly, there is no single definition of what “long term” actually means. Often terms are chosen by convenience, arbitrarily (“next generation”), or based on scientific, yet highly uncertain statistics (e.g., the Paris agreement seeks to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees, and estimates suggest it requires cutting emissions by 50% by 2030).

- Secondly, sustainability is pragmatically accommodated within our existing instrumentally-rational economic paradigm. In other words, corporate decisions are based on financial business cases that seek to maximise profits (in terms of ROI, IRR, NPV of projected cash flows etc). In order to make them more “sustainable”, we extend the temporal horizon when comparing costs and benefits of our actions, whilst (voluntarily) accommodating some “environmental risks”, or offsetting environmental costs. Rather than being profitable next quarter, or within the duration of a current political mandate, we seek to be both profitable and “net positive”, i.e., “have as little impact as possible”, in the long run — let’s say the next 20–50 years. Of course, any such (utilitarian) calculus comes with the usual challenges of translating “externalities” and common goods into monetary terms — for example, by applying VSL (value of a statistical life) calculations to assess the “cost” — sorry I meant: value — of a human life, or by „capitalising nature“ to estimate “residual values” for environmental damage. Moreover, there is no real consensus over what ‘as little impact as possible’ really means and which specific risks are to be considered how — in most cases, we simply add (pretty cheap) SDG projects to annual reports, upgrade (pretty expensive) marketing materials and take cute (and super cheap!) selfies with smiling school children next to our factory in Africa. Whilst we are thus busily trying to turn sustainability into yet another sales opportunity, competitive advantage or greenwashing — we conveniently confuse the world with an industry of new accounting and communication practices (think ESG!). And in the meantime, we continue happily as before: treating life as our — well, almost — unlimited resource and refusing to more fundamentally question the purpose of organisations in a societal and natural ecosystem.

- Thirdly, even when people earnestly try to take a more principled approach to sustainability, opinions as to what exactly that implies and how it could be measured vary widely. Suggesting the need to become “good ancestors”, “treat nature like a person”, or “do good by our children”, people mostly argue for more regulation and stricter limits to economic growth, beyond just voluntary action. Proposals range from doughnut economics and “do no harm” regulations to international treaties to reduce CO2 emissions. But, firstly, any such calls to action are normally thwarted by solemn reminders of politicians that we are all impotent victims of globalised markets. Secondly, a deontic approach — be it based on bioegalitarianism, deep ecology or scientific damage forecasts — often fails to propagate goodness; as we know from much research, compliance codes quickly erode any natural predisposition of actors to behave ethically. Thirdly, the expedient fuzziness of the concept makes it impossible to derive consistent and effective legislation; suggested legal limits are mostly arbitrary and only represent minimum consensus, rather than contingent optimums. Yet, maybe even more importantly, much of the vocal activism remains focused on external damage regulation — rather than the development of inner consciousness and better educational and institutional practices. Collectively, we often fail to reflect more deeply about what it really means — in terms of our own behaviours — to live a good life, and to collectively craft good organisations and a good economy. As Ed Freeman once said: there is a big difference between “doing right” and doing good.

This leads me to the essential difference between sustainability and responsibility: as per above, sustainability is about maintaining a specific parameter at a certain rate or level — it focuses on the task and its outcomes; thus, corporate sustainability seeks to maintain a specific level of social or environmental well-being (or damage) in the future. Its typical image is some version of a Venn diagram, representing a triple (or quadruple) bottom line. Conversely, responsibility is the state of being accountable — it focuses on the character of the actor and their principles. Corporate responsibility, therefore, reflects on the fundamental accountability of business to contribute to society, through all its activities, and accepts an existential obligation to take care of society and planet, and their needs. It thus refers to inner standards, based on an objective duty towards humanity, justice and ethical norms (think Adam Smith’s impartial spectator who represents “the eyes of mankind”). It’s typical image is a diagram of concentrical circles, with an all-integrative ideal of the “good life” at its core, upon which society is founded, and which the economy sustains.

Of course, sustainability and responsibility overlap and can combine — as Ricardo Torelli suggests: “being sustainable and taking care of your present and your future by not exploiting resources more than there are, easily translates into responsible behaviour, in which you are taking care of someone/something according to their problems and needs”. In other words, it is of course possible to both act in a principled fashion (stopping pollution now if it is ethically wrong), and to take a long-term and multi-stakeholder perspective on consequences (e.g., by ensuring appropriate measures to mitigate negative implications or optimise outcomes from responsible action). However, this is often not what happens in business. As a matter of fact, sustainability is often claimed without fundamentally changing the way we work. For example, when a company in the oil & gas sector “offsets” dangerous emissions by acquiring carbon credits, or by installing photovoltaic systems on the roof of all its premises. Or when Qatar claims to run a “sustainable” world cup by installing greenery in all stadiums and build a few wind turbines. Or when you and I continue to use corporate travel, but pay a few dollars to “make the travel green”.

Essentially, sustainability does not necessarily imply, demand or enhance ethical responsibility. It therefore can incentive a marginal and superficial — if not fraudulent — logic for action. By the same token, it is conveniently argued that the limits to growth can be changed towards a new paradigm “to grow the limits” – we don’t need to produce less, but simply require more technology and innovation to help us “grow the pie”! Thus, our modern economic emperors proudly sport sustainable new clothes, and continue to advocate paracetamol against cancer. That’s why it is no surprise that younger generations increasingly question the credibility of corporate and political actors. And, sadly, the UN’s SDGs, with all its laudable effort to mitigate environmental degradation, might unwittingly (?) contribute to the survival of exactly the type of economic system which causes the damage it seeks to reduce in the first place. Sustainability becomes a hegemonic societal discourse that, above all, ‘sustains’ the powers and structures that are already there.

In conclusion, the truth is pretty simple: we all might feel good about ourselves by advocating sustainability and long-termism, but if we really want to build a better system, we must seek to understand what makes our societal system worthy of being sustained in the first place. We must be willing to take personal care of the world and of each other; we must agree and enact mutual ethical responsibility; and we must accept that it will come with personal and collective sacrifices, commitment and costs. Because if something is wrong, it’s wrong — however sophisticated our attempts to make it look sustainable might be.

Popular articles in the KnowledgeHub: Good Society

“Act as if what you do makes a difference. It does.” - William James

.

.