F**k Purpose!

(25 min read)

Meet Frank Martela, a refreshingly unconventional Finnish philosopher on a stimulating quest to unlock the secrets of a meaningful life. Frank melds Dewey's pragmatism, the insights of Self-Determination Theory, and the moral compass of Virtue Ethics to develop a journey for transforming individuals and organizations. Together, we unravel the challenges of his theoretical project and dive into its practical implications - from 'caring connections' at work and the hurdles of self-management to the benefits of systems intelligence. Join the conversation if you still wonder whether people in the Nordics are happier because of saunas and heavy metal, and, of course, if you are keen to pursue a more meaningful life at work.

Jump to

Why is the interview important? Who are we talking to?

FRANK MARTELA

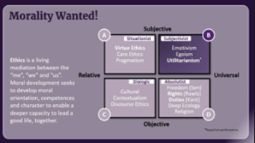

We approached Frank for several reasons. Firstly, we wanted to get clearer about a possible distinction between "goodness" and "meaning", as well as between normative ethics and mostly descriptive psychology. Helpfully, Frank has dedicated decades of his researcher life to questions about meaning, meaningfulness, significance and self-realization at work or in life. Secondly, we wanted to explore whether and how virtue ethics could benefit from integration with (positive) psychology, as a normative foundation for our theory. Frank has developed multiple iterations of a practical framework that seemed very interesting. This also links to our interview with Blaine Fowers which seeks to explain "telos" in anthropological and evolutionary terms. Finally, we wanted to again explore (the limitations) of pragmatism in the context of morality. Here, we also connect with our interview with Ed Freeman.

Frank Martela is a cross-disciplinary researcher with a PhD in both philosophy (University of Helsinki) and organisational research (Aalto University). He is a University lecturer at Aalto University and docent of well-being psychology at the University of Tampere and has spoken to hundreds of audiences worldwide, with lectures at Universities on four continents, including Stanford University and Harvard University. His steadily expanding research was published in numerous academic journals within psychology, philosophy and organisational design. As an expert in the meaning of life, Frank has been interviewed for the New York Times, Le Monde, Die Süddeutsche Zeitung and many others.

In addition to his academic work, Frank is also one of the co-founders and current chairman of the board of Filosofian Akatemia Oy, a company with expertise in measuring engagement, motivation and meaningfulness at work and consulting organisations on how to make work-life better. His most recent book is called “A Wonderful Life”.

Exploring the concepts for this session

A Resource Kit to launch your explorations

Selected published works

Live video recording and podcasts

What have we learned? Our "Best Bit" takeaways from the Interview

KEY INSIGHTS from the interview FOR OUR INQUIRY

Here you can find the most memorable insights from our interview, related to our three inquiry questions. Simply select from the drop down menu on the right -->

Share the most popular quotes on social media: Just click + save picture + post!

Unleash your curiosity and discover new insights

Further explorations about (the linkage between) reality (ontology), morality (ethics) and meaning of life

Further explorations about meaningful work

Related blog posts

(3 min read)

Explore all the popular interviews in this section