Sustain-ability: To Become or Not To Become?

(3min read)

Ed Freeman is one of the most important contemporary philosophers. Famous for his "stakeholder theory", Ed advocates a "pragmatic" approach to business ethics, in contrast to Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). We challenge the risk that stakeholder capitalism simply amplifies a utilitarian and extractive paradigm, and examine the need to develop a better narrative for business. We discuss how ethical stakeholder management can be effectively operationalised. We talk about music, martial arts and the role of business schools in the development of ethical leadership. The result was a brilliant and vibrant conversation.

Jump to

Why is the interview important? Who are we talking to?

ED FREEMAN

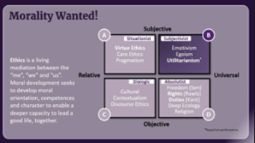

We approached Ed, because for nearly 50 years Ed has developed stakeholder theory (in spite of Klaus Schwab claiming it as his invention) as one of the most important narratives to counter a business ethic founded on single-minded shareholder value maximisation. Ed consistently emphasizes that ethics and value judgments are integral components of sound business decisions, rather than philanthropic add-ons (as he suggests CSR sometimes advocates) or undue taxation (as argued by Milton Friedman). Furthermore, Ed contends that stakeholder engagement can generate value for all parties involved. Finally, Ed is a convinced pragmatist, and his writings helped us much to see how pragmatism unfolds in practice, and where its limitations lie.

Ed is an American philosopher and Elis and Signe Olsson Professor of Business Administration at UVA Darden School of Business. He is best known for his work on stakeholder theory. Besides his six honorary doctorates, he has received Lifetime Achievement Awards from the World Resources Institute and Aspen Institute, the Humboldt University Conference on Corporate Social Responsibility, the Academy of Management and the Society for Business Ethics. Ed is a prolific writer and his books, such as “Strategic management — a stakeholder approach”, “Managing for Stakeholders” and “Stakeholder Theory” are seminal works, and his articles are frequently cited.

Besides his passions for writing, making music and martial arts, teaching is close to his heart. The ability to enable students to think critically and take different perspectives earned him several awards throughout his career. Moreover, Ed suggests that “we are only as good as the stories we tell” — he has worked with many executives and companies around the world to enable new narratives and help to make business and ultimately the world a little better.

Exploring the concepts for this session

A Resource Kit to launch your explorations

Selected published works

Live video recording and podcasts

Explanations, artefacts and references from the interview

What have we learned? Our "Best Bit" takeaways from the Interview

KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE INTERVIEW FOR OUR INQUIRY

Here you can find the most memorable insights from our interview, related to our three inquiry questions. Simply select from the drop down menu on the right -->

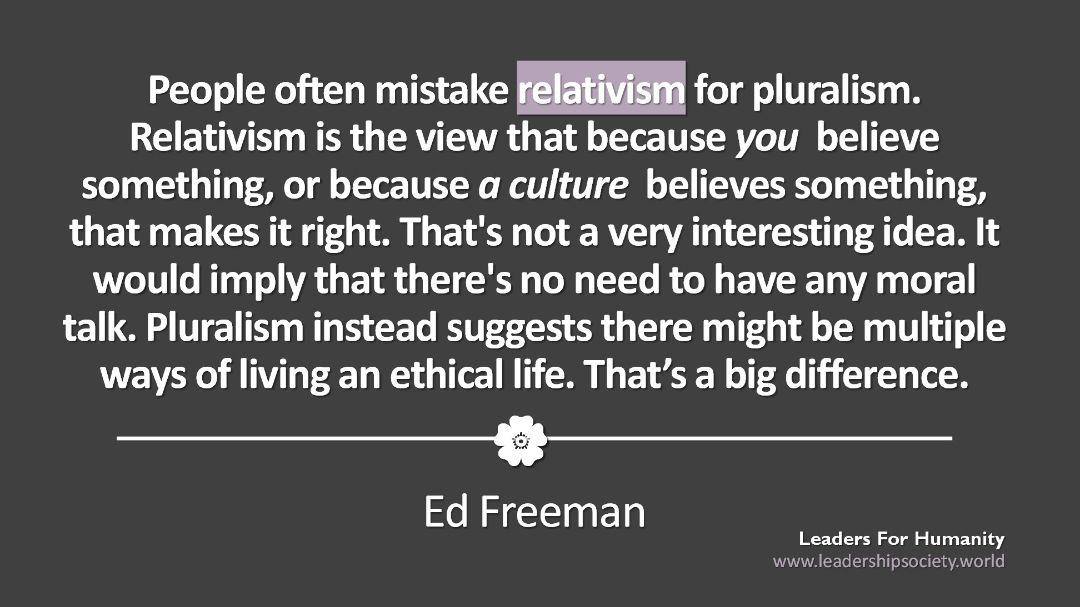

Share the most popular quotes on social media: Just click + save picture + post!

Unleash your curiosity and discover new insights

Further reflections on pragmatism and business ethics

How can we develop responsible leadership?

Related blog posts

(3min read)

(3 min read)

Explore all the popular interviews in this section