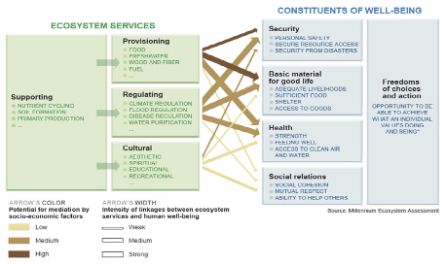

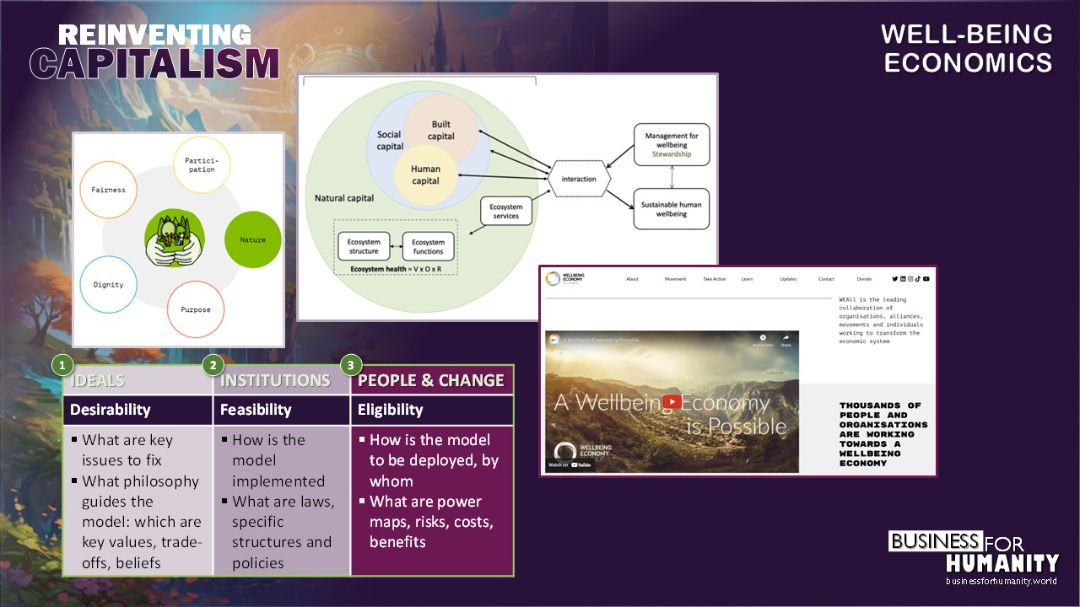

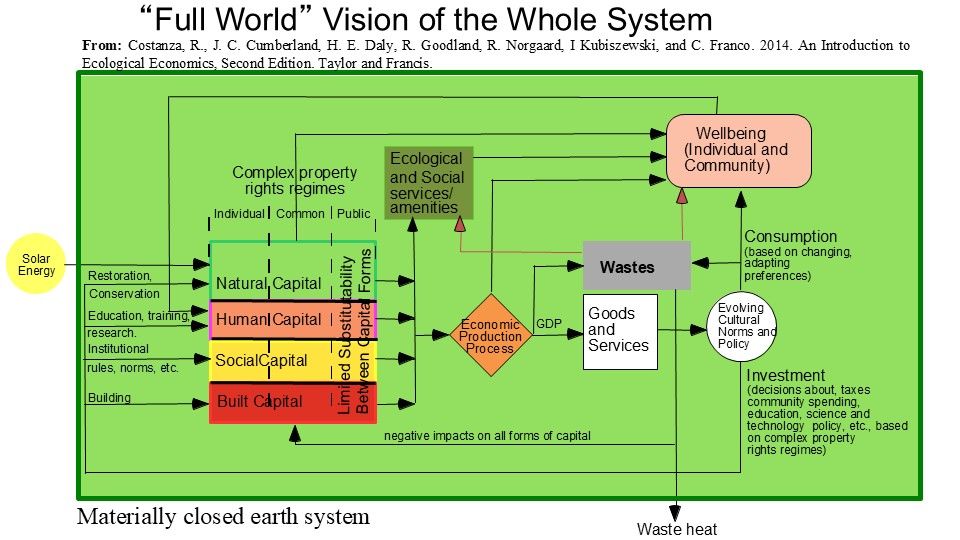

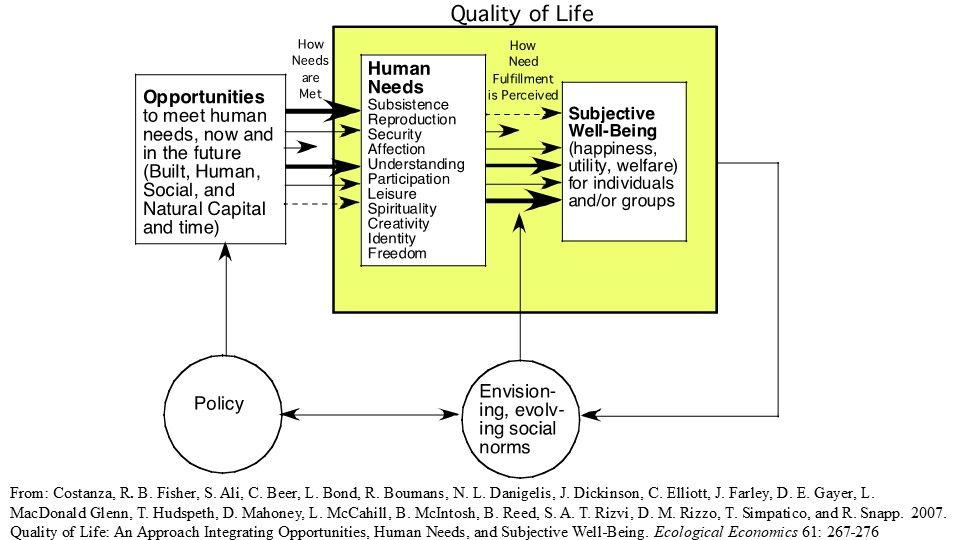

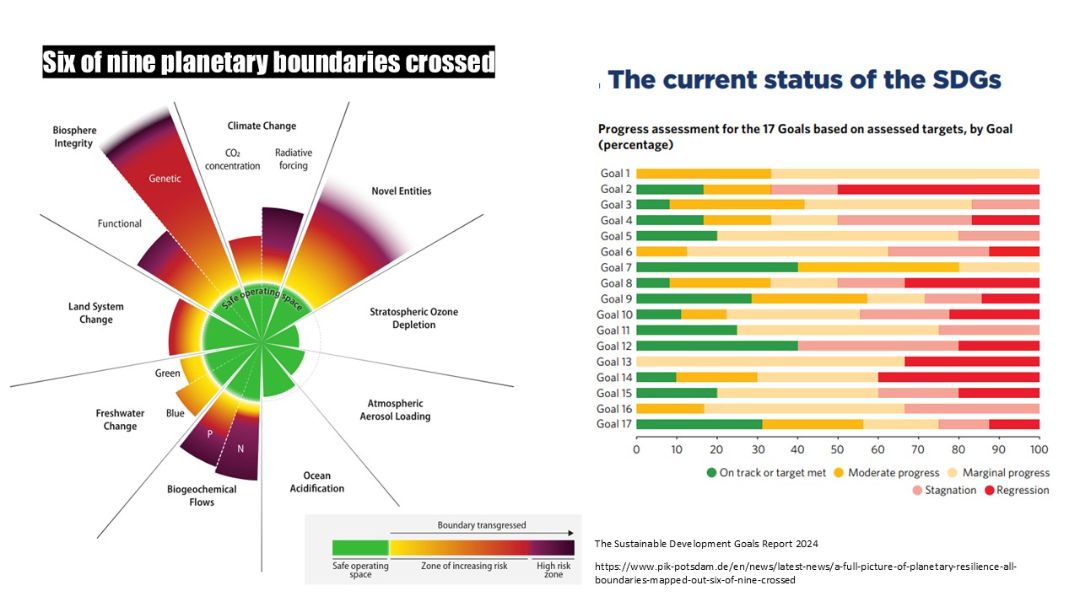

The primary policy focus for shaping or reshaping institutions is the improvement of sustainable human well-being (SHW). This is measured using indicators such as the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI), which adjusts GDP by accounting for the depletion and degradation of natural resources and correcting for inequality. Additional Quality of Life Indicators help design institutions that meet human needs, enhance subjective well-being, and ensure ecological health.

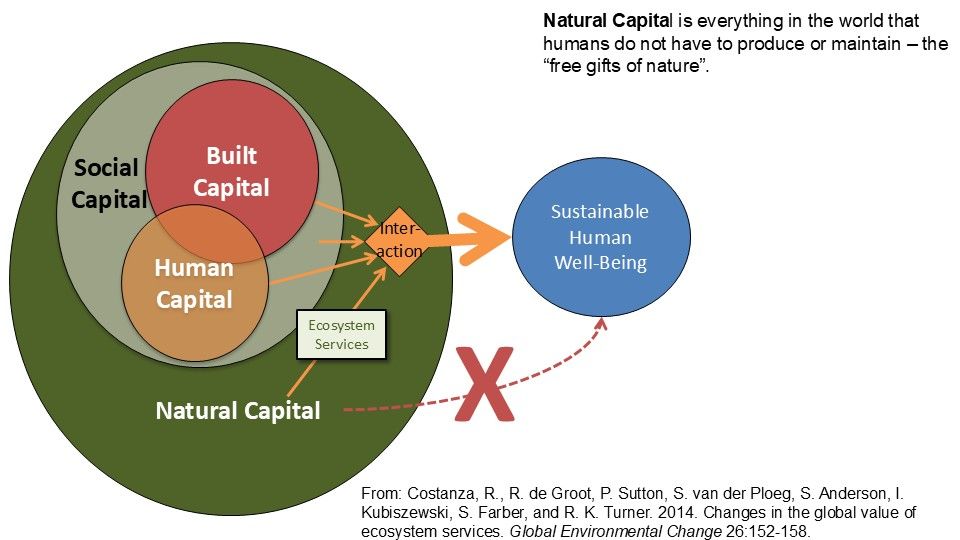

Wellbeing Economics (WE) develops a broad range of policy measures to steer the transformation of the economy and society towards a post-growth paradigm. The government plays a critical role in facilitating a better economy by facilitating a shared vision, regulating and policing the market, planning and coordinating a reduced-growth regime, and propertising non-marketed natural and social capital assets. Here the emphasis is to align property rights with nature and scale of the system, linking rights with responsibilities, and expanding common-property institutions.

1. Regulation and industrial policy: respecting ecological limits- Establishment of systems for effective and equitable governance and management of the natural commons, including the atmosphere, oceans, and biodiversity, and sustainability planning, and a legally binding mandate to manage them for the equal benefit of all citizens, present and future. Common assets trust (CAT) would cap resource use at rates less than or equal to renewal rates, which is compatible with inalienable property rights for future generations.

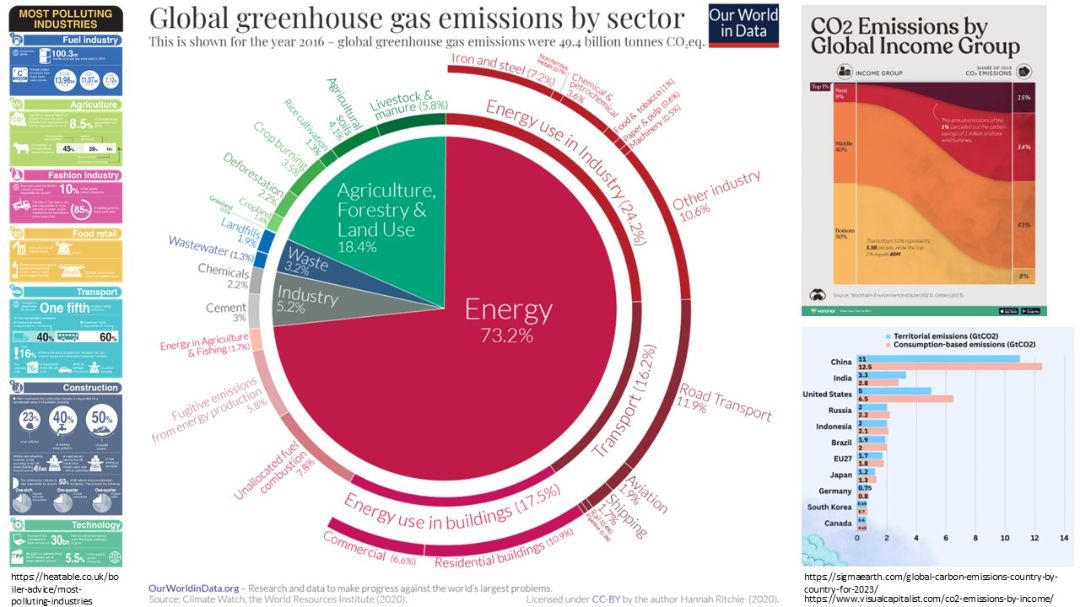

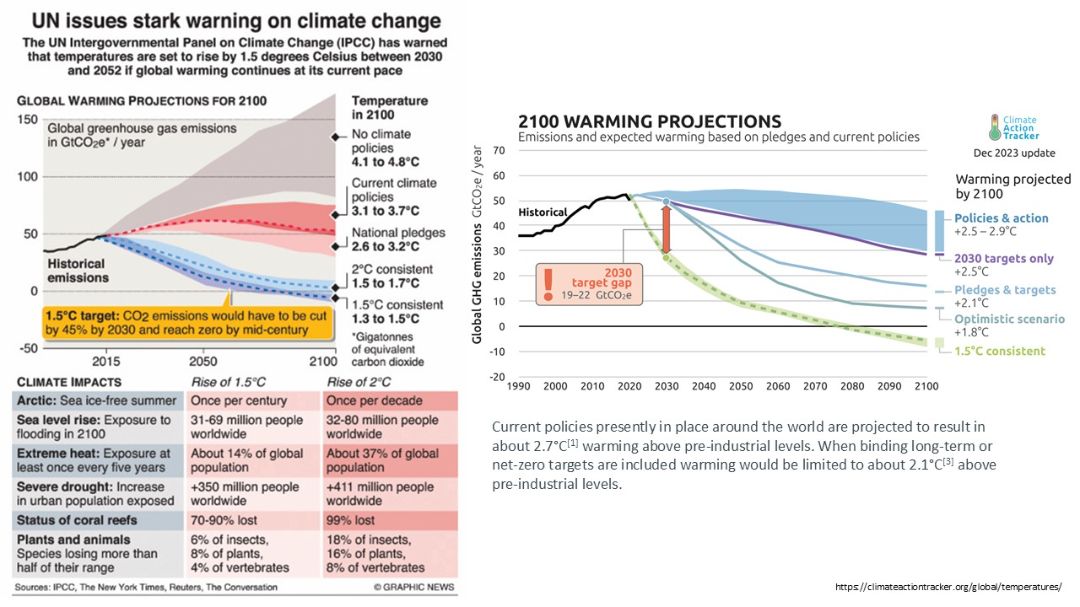

- Creation of cap-and-auction systems for basic resources, including quotas on depletion, waste emission, pollution, and greenhouse gas emissions, based on basic planetary boundaries and resource limits (extraction rates not to exceed regeneration).

- Consuming essential non-renewables, such as fossil fuels, no faster than we develop renewable substitutes. Support for local production and sufficiency (e.g. private gardens for community food needs, smart grids) and ecological "living" buildings.

- Investments and R&D in sustainable infrastructure, such as renewable energy, energy efficiency, agriculture, public transit, watershed protection measures, green public spaces, and clean technology.

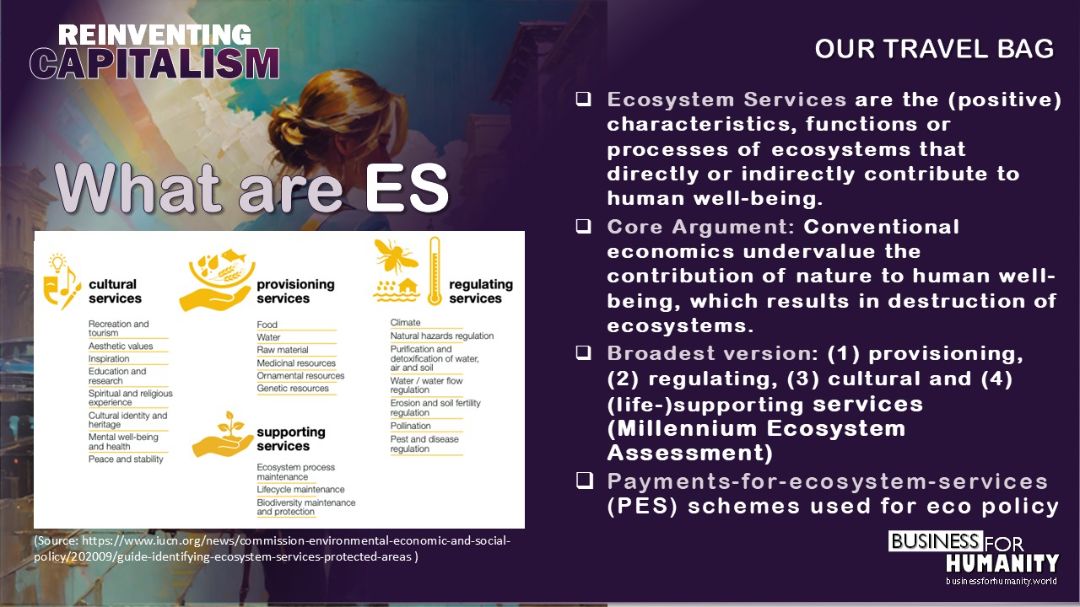

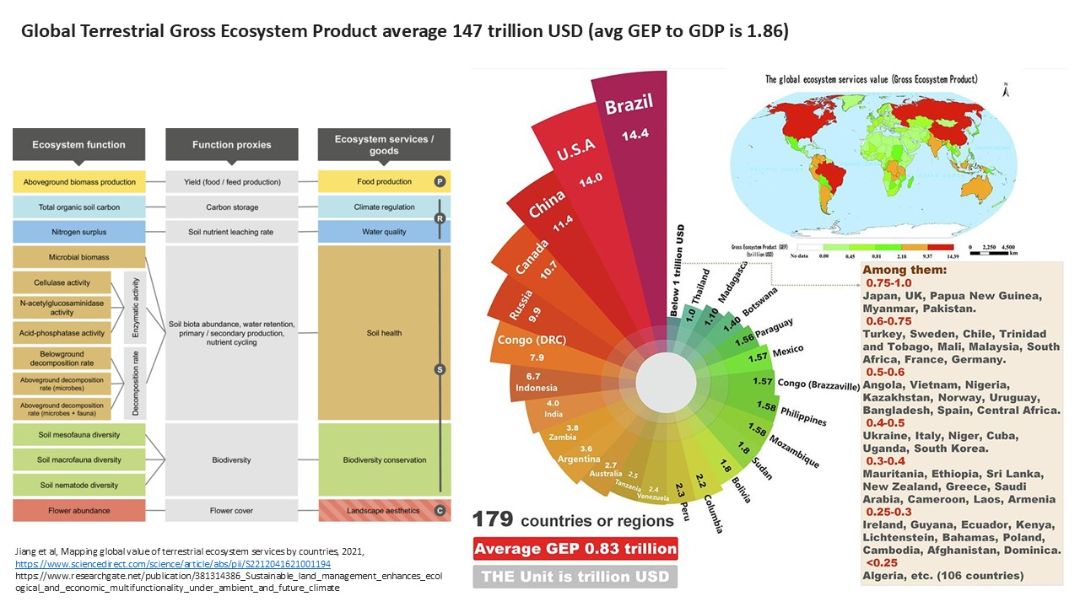

- Systems of cooperative investment in stewardship (CIS), payment for ecosystem services (PES), policies to increase the cost of degrading natural capital, and green taxes

- Ensuring availability of all information required to move to a sustainable economy that enhances well-being through public investment in research and development and reform of the ownership structure of copyrights and patents

- Policies to address population growth.

2. Redistribution and social shaping: protecting capabilities for flourishing

- Establishment of a system for effective and equitable governance and management of the social commons, including cultural inheritance, financial systems, and information systems like the Internet and airwaves.

- Broad participation requires the removal of distorting influences like special interest lobbying and funding of political campaigns. Specific policies are needed to create and protect shared public spaces; strengthen community-based sustainability initiatives; reduce geographical labor mobility; provide training for jobs in sustainability; offer better access to lifelong learning and skills; place more responsibility for planning in the hands of local communities; and protect public service broadcasting, museum funding, public libraries, parks and green spaces.

- Sharing the work to create more fulfilling employment and more balanced leisure-income trade-offs. Specific policies should include: reductions in working hours; greater choice for employees about working time; measures to combat discrimination against part-time work as regards grading, promotion, training, security of employment, rate of pay, health insurance, etc.; and better incentives to employees (and flexibility for employers) for family time, parental leave, and sabbatical breaks.

- Reducing systemic inequalities, both internationally and within nations, by improving the living standards of the poor, limiting excess and unearned income and consumption, and preventing private capture of common wealth. Minimum and maximum income. Redistributing wealth and income through a tax system that taxes consumption and throughput of resources rather than income and unearned rent (e.g., high taxes on land values excluding improvements)

- Increased financial and fiscal prudence, including greater public control of the money supply and its benefits and other financial instruments and practices that contribute to the public good. Moving towards 100-percent fractional reserve requirements for commercial banks and restricting their activities.

- Strong community building, urban redesign (green spaces, "20 minute neighbourhoods" integrating basic services within 20 minute walk), local currencies

- Education about civic responsibilities, basic moral values and a common set of cultural practices and expectations is heavily stressed

- Reforming work structures and recognizing the value of caring and well-being-enhancing services to society

- Other redistributive mechanisms and policies could include improved access to high- quality education, anti-discrimination legislation, implementing anti-crime measures and improving the local environment in deprived areas, and addressing the impact of immigration on urban and rural poverty.

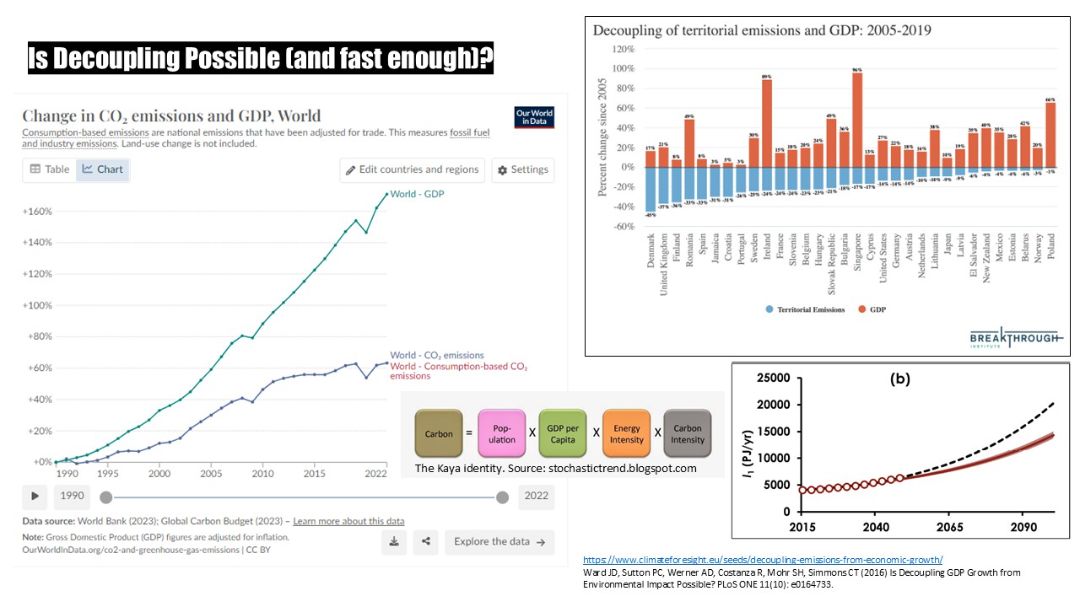

3. Market shaping: changing production and consumption patterns- Enforce use of full-cost accounting measures to internalize externalities, value nonmarket assets and services, reform national accounting systems, and ensure that prices reflect actual social and environmental costs of production.

- Significant reduction of market activity in the wealthy nations. Objective should be to minimise GDP while maintaining high quality of life.

- Restructure larger firms as public or quasi-public enterprises jointly owned by workers, or cooperative and municipal institutions. Support for benefit corps.

- Dismantling incentives towards materialistic consumption, including banning advertising to children and regulating the commercial media (e.g. banning advertising in public spaces, tax advertising etc). "We do not need television, we need entertainment and information."

- Policies to target the composition of production and consumption to ensure less and cleaner consumption, and avoid rebound effects. Taxes on luxury consumption. redirection of consumption from private status goods to public goods, increasing employment in specific sectors (health, green projects, community projects), shifting investment towards clean energy, redistributing surpluses from private consumption to communal activities (urban food gardens recycling, car pooling), incentivising voluntary self-restrictions,

- Fiscal reforms that reward sustainable and well-being-enhancing businesses and actions and penalize unsustainable behaviours that diminish collective well-being, including ecological tax reforms with compensating mechanisms that prevent additional burdens on low-income groups.

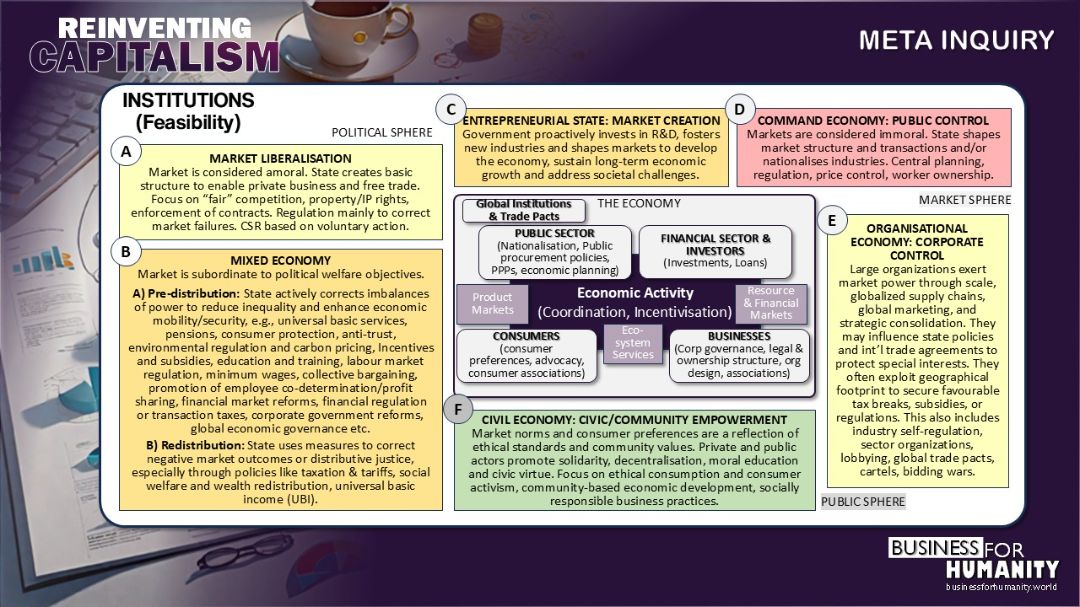

Institutional changes are deemed necessary across several domains. Addressing market failures can be achieved through mechanisms like cap-and-auction systems. Pre- and redistribution can be facilitated by new tax systems, regulations on marketable goods, and the conduct of market participants. Additionally, altering work and consumption patterns is crucial. WE also emphasizes changes in property regimes, advocating for the creation of more common assets and the promotion of worker cooperatives. Lastly, a more participatory democracy, especially at the local level, along with comprehensive information and education, is essential to enable all the proposed institutional changes.

.

.