A) Political Institutions

The Economy for the Common Good (ECG) proposes a comprehensive approach to political institutions aimed at fostering democratic participation and prioritizing the common good. The ECG envisions a three-step direct democracy involving representative, direct, and participative democracy, with a focus on cooperative procedures rather than factional competition and a bottom-up democratic process to counteract the influence of elites and safeguard societal interests. Economic conventions at the municipal, regional, and national levels serve as forums for democratic deliberation and decision-making. These conventions facilitate discussions on specific issues, such as democracy, economy, education, public services, and media, leading to the evolution of a democratic economic order. The Common Good Balance Sheet serves as a central political incentive tool, measuring enterprises' contributions to the common good. Seventeen Common Good indicators assess various aspects of a company's operations, and these indicators are subject to democratic discussion and decision-making processes to ensure relevance and adaptability over time. These balance sheets are legally binding, publicly accessible, and subject to external audit to ensure transparency and accountability. Additionally, the ECG advocates for the removal of systematic drivers of growth. Key regulatory measures include scaling corporate profit taxes according to Common Good Balance Sheet results, and inheritance tax reforms to prevent wealth accumulation. It suggests a mixture of private, public, and communal property rights, with restrictions to prevent excessive inequality. Additionally, the ECG proposes global regulation to ensure fair trade and sustainable resource management.

B) Economic Institutions

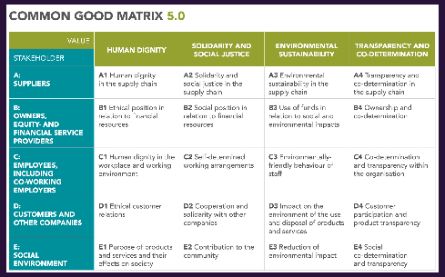

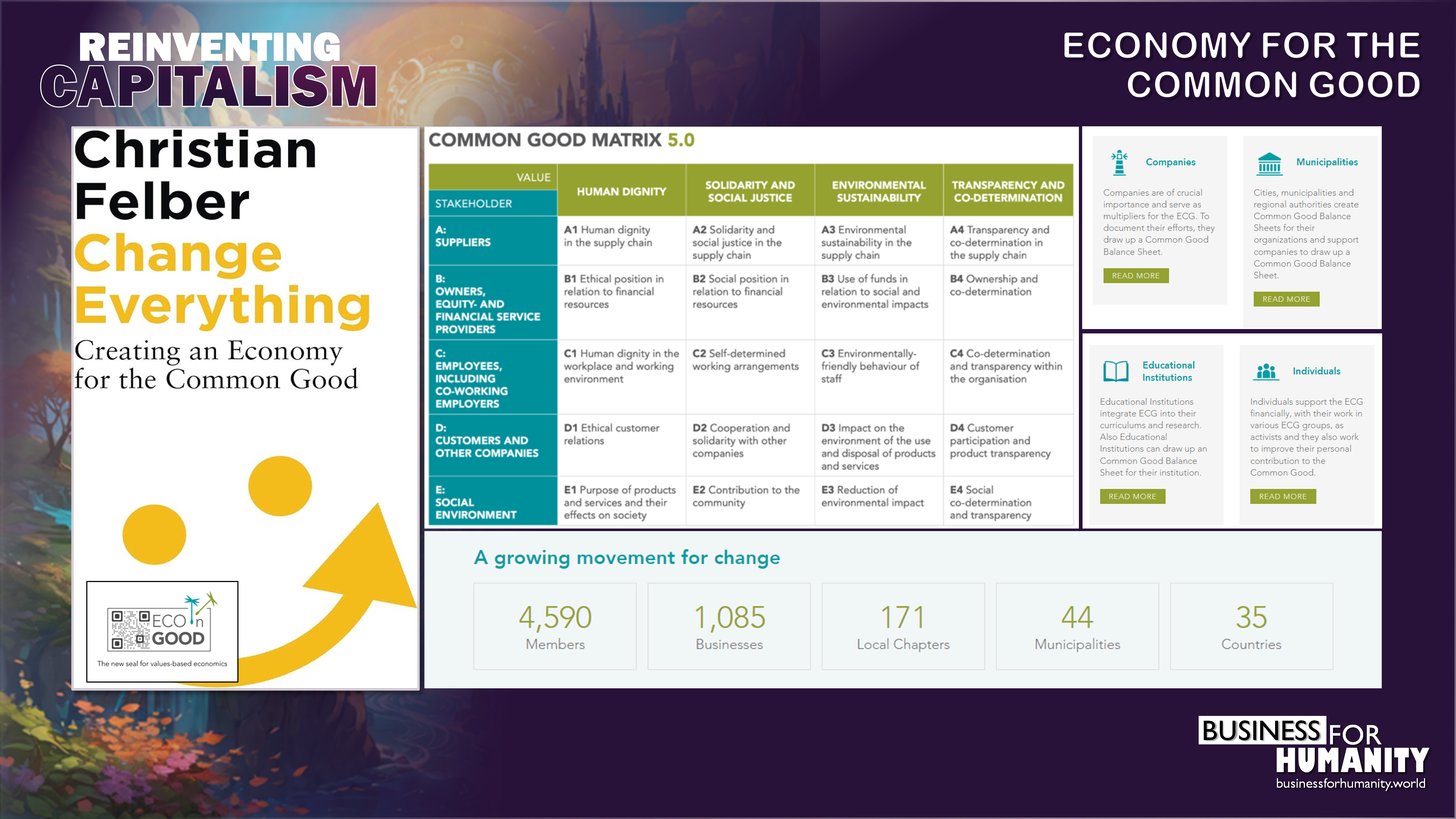

The ECG envisions an economic order where the pursuit of the common good is the overarching goal of business. It promotes a cooperative market economy where competition is subordinate to cooperation, and private enterprises coexist with "democratic commons" such as energy supply companies and schools. This reorientation entails a reversal of the prevailing incentive structure, prioritizing cooperation and the common good over profit and competition. Key institutional changes include replacing traditional metrics of economic success with indicators focused on non-monetary values such as satisfaction of needs, quality of life, and the common good. A Common Good Product would replace GDP, whereas the ethical return on investment would displace financial return as the primary parameter of economic success. Enterprises are encouraged to to supplement their financial balance sheet with a Common Good Balance Sheet, which assesses their social responsibility, ecological impact, democratic practices, and solidarity - for example, how cooperative they are with other companies, whether their products and services satisfy human needs, and how humane their working conditions are and whether income is fairly distributed. Enterprises with favorable Common Good Balance Sheet results receive legal advantages, such as tax incentives and preferential treatment in public procurement.

B1) Finance

The ECG proposes a radical transformation of finance and banking, forbidding to "make money from money". Financial markets would cease to exist, with money as credit becoming a public good. Regional common good stock markets would replace central capitalistic ones, financing enterprises without trading them. The Democratic Bank would offer loans to common good-qualified companies at fixed rates just above cost to avoid pressure on economic growth, with democratically elected supervisory boards ensuring accountability. Investment banks would be abolished, and other banks would operate in non-profit-oriented forms. The government and parliament would have no access to the Democratic Bank, which would be transparently controlled by the sovereign people. Income would be earned through work rather than capital, with limitations on use of investment and . Commodity prices would be fixed democratically, and hostile takeovers would be forbidden. A global "globo" currency would be introduced to support international Common Good trade zones.

B2) Organisations

Important ECG objectives are to promote the democratization of enterprises, a fairer distribution of company results and employee ownership schemes. It advocates, among many other measures, for restricted reserves from profit and a gradual annual decrease in profits exclusively benefiting founders in favor of broader ownership distribution among employees. It also prohibits dividend payouts to non-working proprietors and advocates for statutory maximum and minimum wages, with income limits set as a small multiple of minimum wages. Additionally, the ECG advocates for reducing regular working hours and introduces periods of regular leave to foster appreciation for non-work-related activities. It also promotes shared crisis commissions to address economic downturns, with companies producing lowest common good to be closed first.

.

.