We Need to Start the Transformation With Ourselves

(5 min read)

Mats Alvesson is a renowned Swedish organizational researcher, celebrated for his critical contributions to management and leadership studies. In our thought-provoking interview, we explore the challenges of a postmodern society, marked by fear, emptiness, and a dearth of valuable knowledge production. Transitioning from societal context to organizational culture, we delve deeper into the perils Mats identifies as "Functional Stupidity." Our conversation sheds light on the common pitfall of leaders failing to ask the right questions, often succumbing to unquestioning conformity within organizations, including academic institutions. Drawing on Mats' extensive expertise, we critically examine fashionable concepts in mainstream organizational theory, encompassing discussions on identity, culture, and leadership. Mats adeptly dismantles prevalent management myths, emphasizing the imperative of critical thought in effective management and leadership. Join us for an illuminating discussion on how to avoid the perils of leadership in the complex landscape of modern organizations.

Jump to

Why is the interview important? Who are we talking to?

MATS ALVESSON

Our decision to interview Mats Alvesson stemmed from three central motivations, each intricately tied to his influential work.Firstly, we were deeply intrigued by Mats' profound engagement with critical theory. In tandem with our prior discussion with Simon Western, we aimed to delve into the theoretical foundations, historical evolution, and legitimacy of critical theory in psychology, sociology and philosophy (both critical theory in general and "Critical Theory" related to the Frankfurt School). We sought to understand its multifaceted connections to Marxist theory, social constructionism, poststructuralism, linguistic analysis, and communicative theories, and how it impacts organizational research.

Secondly, Mats' pivotal role in the application of critical theory to management and him being a leading scholar in critical management studies, held for us significant appeal. His work has helped to trigger a paradigm shift in the field of management, unveiling the underlying power structures, discourses, and ideologies that underpin mainstream managerial concepts and practices. We were keen to discuss how his evolving critical approach not only offers a fresh lens through which to view organizational dynamics, but also has the potential to improve organizational practices.

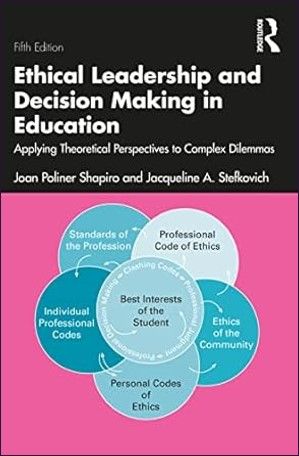

Lastly, Mats' exploration of the concept of "Functional Stupidity" and its implications for leadership education proved captivating. Mats' insights into leaders' tendency to neglect vital questions in a landscape marked by conformity, 'templated' non-conformity and a dearth of critical thinking, resonated strongly. This theme connects with our focus on practical wisdom and started to link it with social practices and structures. We were keento uncover Mats' perspective on leadership education, with the ultimate goal of discerning how to nurture critical thinking and establish practices to catalyze positive organizational transformation.

Mats Alvesson is a distinguished Swedish organizational theorist and researcher, celebrated for his profound contributions to the fields of management and leadership studies. Since 1994, he is Professor in the Department of Business Administration at Lund University, Sweden, as well as honorary Professor at the University of Queensland Business School, Brisbane, Australia, visiting professor at Stockholm Business School, and visiting Professor at Cass Business School, London. His professional career has been marked by esteemed positions at various universities, including Concordia University in Montreal, Linköping University, Stockholm University and Gothenburg University and he has held roles of acting or visiting professor at numerous institutions worldwide, including Åbo Akademi, Copenhagen University, University of Colorado, Boulder, Exeter University, and others.

Alvesson has served as a member of several editorial boards for prestigious academic journals, including the Journal of Management Studies, Human Relations, and Academy of Management Review, and has been an active reviewer for numerous journals in the fields of management, psychology, and organizational studies. His impressive research endeavors have earned him substantial research grants, such as those from the Swedish Trade Bank's research foundations, the Work Life and Social Science Research Council, and Vinnova. His research, contributions, and thought leadership continue to shape and advance the realms of organizational theory, critical management studies, and leadership research.

Exploring the Critical concepts for this session

A Resource Kit to launch your explorations

Selected published works

Live video recording and podcasts

Explanations, artefacts and references from the interview

What have we learned? Our "Best Bit" takeaways from the Interview

KEY INSIGHTS FROM THE INTERVIEW FOR OUR INQUIRY

Here you can find the most memorable insights from our interview, related to our three inquiry questions. Simply select from the drop down menu on the right -->

Share the most popular quotes with your social media connections: just click + save picture + post!

Unleash your curiosity and discover new insights

Further explorations about critical theory and postmodernism

Further explorations about moral leadership education

Explorations into Reflexivity and Hermeneutics

Related articles

(5 min read)

(2 min read)

Pursue your inquiry further with other popular interviews in the same section