What unites our traditional leadership approaches is that the lens of analysis is fixed on the leader: on his traits, his behaviour, his-strategy-in-context, his mindset. And I will argue that most of these interpretations - at least in part - are missing a point. Leadership is not just about the leader. Good leadership is about making a new potential reality possible; about transforming the capacity of an organisation "to become" its own best future.

Do you remember Steve Covey's seminal Seven Habits? There was a time during the 1990ies when it was one of my favorite management books. If you happen to remember it, you might also recall his memorable story about the difference between management and leadership. At some point Steve writes: whilst MANAGERS are cutting a path through the woods, busily seeking to organise their work efficiently…"the LEADER is the one who climbs the tallest tree, surveys the entire situation, and yells, 'WRONG JUNGLE!'"

This was one of my all-time favorite leadership quotes, right up there with J.Q. Adams's "If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more, and become more, you are a leader."; and Jack Welsh's "Before you are a leader, success is all about growing yourself. When you become a leader, success is all about growing others". Yes, I know, I'm forever tainted by Anglo-Saxon business education!

By the way, the tale continued: "… Busy, efficient producers and managers often respond… 'SHUT UP! We're making progress!'" Boy, did we, the alleged 'future leaders', feel smug about ourselves!

Alas, what's the big deal, you might say - a few innocuous quotes… Well, I tend to disagree. I have a suspicion that those narratives and metaphors are very important. These stories and myths we get told and tell ourselves, especially during our formative years, fundamentally shape how we think, how we make meaning, how we construct our identities, and, ultimately, how we act. There's absolutely no doubt in my mind that in those years, and for a few decades afterwards (sic!), I desperately wanted to be that visionary, inspirational, self-less (well, probably in a rather immature way) and heroic leader! In hindsight, I can only say: mistakes were made!

In fact, in retrospective I'm pretty certain that those were not very "good" quotes. Beside the fact that when I was young I had many answers, and now, being old, I've got lots of questions… I do believe that those citations emblematically oversimplify what leadership should be about, and how to go about it… Let me explain.

Apart from the triumphantly nonsensical juxtaposition of leadership vs management, which Henry Mintzberg so eloquently unravels; apart from an immensely detrimental reification of leadership that has so dramatically misled the whole leadership genre - crowding out alternative discourses and forcing important dynamics of organisational life into the shadow (think about: pride, power, patriarchy, anxiety, vulnerability); apart from the simplistic and neo-liberal caricaturisation of the economy as a "competitive jungle"; and apart from unduly sustaining a "heroic" and arrogant leadership discourse that cements narcissism, developmental immaturity, positional power and eventually the status quo… apart from all of this, there's something else.

Think about that first quote again: whilst everybody is literally lost in the weeds, the leader rises up the ladder, scours the horizon and… points to the truth. (By the way, this image might be recalling both the "hero" as well as the "saint" leadership metaphor, by Mats Alvesson's definition). My question is: what does this image teach us about how good leadership is developed? There could be different ways to read the metaphor, and we have tried them all:

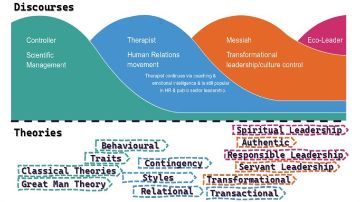

- Traditionally, we have sought to analyse the personal characteristics of that single, glorious leader and tried to develop them (note: this is the leadership "trait theory")

- When that did not quite work, we started to analyse the behaviour of the leader, i.e., how he [sic!] chose his direction, rallied his people, communicated the new course (so-called leadership "style theory")

- Thereafter, we situated the climbing of the ladder in the context of the 'type of jungle', the 'task at hand', the 'position of the leader' and the 'environment' in order to derive those factors that made his leadership successful (this was called "contingency theory");

- Finally, we looked at the "mindset" of the leader - how he lifted himself beyond the thicket of the fixed and mundane, climbing that "ladder of consciousness", in order to discover the endless 'forest for the trees' (i.e., "cognitive development theory").

What unites all of these approaches is that the lens of analysis is fixed on the leader: on the leader himself, his behaviour, his-strategy-in-context, his mindset. And I will argue that most of these interpretations - at least in part - are missing a point. Leadership is not just about the leader. Good leadership is about making a new potential reality possible; about transforming the capacity of an organisation "to become" its own best future.

In other words, and to stay with the image, it is about the "pointing of the finger". Gert Biesta calls the symbolic act of "pointing" an existential "gesture of disruption". It is not about the leader, nor about the direction itself, but about the interruption of my current reality. The leader's motion makes ME pay attention to something important. I am pulled out of my habitual behaviour to notice something that summons me- the organisation or the individual - into my being, to take a stand and make important choices. That very act of interruption opens a crevice of potentiality, an affordance of becoming, of renovation, of nativity.

To be clear, the effectiveness of such an act of interruption isn't dependent on the leader's cognitive intelligence in discerning a specific new course or in providing definite answers; it rather relates to the sensual capacity of the leader to redirect my awareness towards something that has significance, and that calls me to revise my relationship and relatedness with the world. Something that challenges my identity and behaviours, opening up important questions about my Self-in-world - thus enhancing my freedom to 'be'.

Rather than pompously crying out "wrong jungle!", a better leader might have just been silently pointing at that ladder. That's why Leadership is an 'existentially ethical' process. It is not just about "how we SEE things", i.e., about discovering a new map of the territory - what we call "constructivism", or popularly known as "consciousness". Within such an epistemology, the enlightened individual always remains an 'ego in the centre', busily constructing the world in their mind. It is also about a phenomenological "being-in-relation" with the world, about being pulled into the world. That disruptive pointer is not innocuous. It carries the irritating demand of the world not to lead, but to follow - to step responsibly into my fullest freedom. It seeks to enable an organisation or individual to learn "how to BECOME ", growing their innate capacity to act, contribute to, and step into the aliveness of their lifeworld. The gesture of a good leader, much like a good teacher, calls me to look out to the world, and for the world. Such an existential request can ever only work as a gift - it manifests its charism when it arrives without chains of command or control attached. When it reveals itself as a transcendental "us", the primordial energy of life…

Back to that initial story of the leader climbing the ladder. It provides a seductively simple image. And for many years it has shaped my thinking about what it means - and what is expected of me - to be a good leader. But it is not the only way to look at leadership and we must carefully explore other stories, even those that do not frequently get told, because they might be more complicated and less compelling.

In this context, I recall being in a meeting at the Institute of Directors in London with Nigel Farage, pre-Brexit. After an hour into his talk I was both hugely impressed and utterly frightened by the brilliant simplicity of his arguments to leave the EU. His reasons were utterly flawed, even deceitful, but nevertheless powerful and persuasive. The room was boiling with energy! In comparison, all the necessary counterarguments I could think of- albeit more truthful and accurate - sounded dry, complicated and lifeless. And as we know, the Brexiteers won. Narratives are powerful, even when they are wrong.

Maybe we must purposefully re-examine our accumulated truths, stories and favourite quotes once in a while to ensure we are not unwittingly perpetuating an ineffective gospel. On that note, dear Steve, it's time to move on from your forest. But my most sincere thanks go to you, nevertheless! You've provided that initial pointer that made me want to become the 'best leader I could be' and I haven't stopped trying ever since. And I reckon that is truly a story that never ends…

---

COMMENTS & CLARIFICATIONS: Many people came back and suggested that the "pointing of the finger" could be interpreted in many less positive ways, or that Stephen Covey had written a very good book and should not be criticised. I reckon herein lies the difficulty, but also the intention, of bringing across different "epistemological paradigms" that are "deconstructed" in the story. The invitation is to "look beyond" the finger, i.e., the story itself, and instead to reflect about where it might point us.

Do you remember Steve Covey's seminal Seven Habits? There was a time during the 1990ies when it was one of my favorite management books. If you happen to remember it, you might also recall his memorable story about the difference between management and leadership. At some point Steve writes: whilst MANAGERS are cutting a path through the woods, busily seeking to organise their work efficiently…"the LEADER is the one who climbs the tallest tree, surveys the entire situation, and yells, 'WRONG JUNGLE!'"

This was one of my all-time favorite leadership quotes, right up there with J.Q. Adams's "If your actions inspire others to dream more, learn more, do more, and become more, you are a leader."; and Jack Welsh's "Before you are a leader, success is all about growing yourself. When you become a leader, success is all about growing others". Yes, I know, I'm forever tainted by Anglo-Saxon business education!

By the way, the tale continued: "… Busy, efficient producers and managers often respond… 'SHUT UP! We're making progress!'" Boy, did we, the alleged 'future leaders', feel smug about ourselves!

Alas, what's the big deal, you might say - a few innocuous quotes… Well, I tend to disagree. I have a suspicion that those narratives and metaphors are very important. These stories and myths we get told and tell ourselves, especially during our formative years, fundamentally shape how we think, how we make meaning, how we construct our identities, and, ultimately, how we act. There's absolutely no doubt in my mind that in those years, and for a few decades afterwards (sic!), I desperately wanted to be that visionary, inspirational, self-less (well, probably in a rather immature way) and heroic leader! In hindsight, I can only say: mistakes were made!

In fact, in retrospective I'm pretty certain that those were not very "good" quotes. Beside the fact that when I was young I had many answers, and now, being old, I've got lots of questions… I do believe that those citations emblematically oversimplify what leadership should be about, and how to go about it… Let me explain.

Apart from the triumphantly nonsensical juxtaposition of leadership vs management, which Henry Mintzberg so eloquently unravels; apart from an immensely detrimental reification of leadership that has so dramatically misled the whole leadership genre - crowding out alternative discourses and forcing important dynamics of organisational life into the shadow (think about: pride, power, patriarchy, anxiety, vulnerability); apart from the simplistic and neo-liberal caricaturisation of the economy as a "competitive jungle"; and apart from unduly sustaining a "heroic" and arrogant leadership discourse that cements narcissism, developmental immaturity, positional power and eventually the status quo… apart from all of this, there's something else.

Think about that first quote again: whilst everybody is literally lost in the weeds, the leader rises up the ladder, scours the horizon and… points to the truth. (By the way, this image might be recalling both the "hero" as well as the "saint" leadership metaphor, by Mats Alvesson's definition). My question is: what does this image teach us about how good leadership is developed? There could be different ways to read the metaphor, and we have tried them all:

- Traditionally, we have sought to analyse the personal characteristics of that single, glorious leader and tried to develop them (note: this is the leadership "trait theory")

- When that did not quite work, we started to analyse the behaviour of the leader, i.e., how he [sic!] chose his direction, rallied his people, communicated the new course (so-called leadership "style theory")

- Thereafter, we situated the climbing of the ladder in the context of the 'type of jungle', the 'task at hand', the 'position of the leader' and the 'environment' in order to derive those factors that made his leadership successful (this was called "contingency theory");

- Finally, we looked at the "mindset" of the leader - how he lifted himself beyond the thicket of the fixed and mundane, climbing that "ladder of consciousness", in order to discover the endless 'forest for the trees' (i.e., "cognitive development theory").

What unites all of these approaches is that the lens of analysis is fixed on the leader: on the leader himself, his behaviour, his-strategy-in-context, his mindset. And I will argue that most of these interpretations - at least in part - are missing a point. Leadership is not just about the leader. Good leadership is about making a new potential reality possible; about transforming the capacity of an organisation "to become" its own best future.

In other words, and to stay with the image, it is about the "pointing of the finger". Gert Biesta calls the symbolic act of "pointing" an existential "gesture of disruption". It is not about the leader, nor about the direction itself, but about the interruption of my current reality. The leader's motion makes ME pay attention to something important. I am pulled out of my habitual behaviour to notice something that summons me- the organisation or the individual - into my being, to take a stand and make important choices. That very act of interruption opens a crevice of potentiality, an affordance of becoming, of renovation, of nativity.

To be clear, the effectiveness of such an act of interruption isn't dependent on the leader's cognitive intelligence in discerning a specific new course or in providing definite answers; it rather relates to the sensual capacity of the leader to redirect my awareness towards something that has significance, and that calls me to revise my relationship and relatedness with the world. Something that challenges my identity and behaviours, opening up important questions about my Self-in-world - thus enhancing my freedom to 'be'.

Rather than pompously crying out "wrong jungle!", a better leader might have just been silently pointing at that ladder. That's why Leadership is an 'existentially ethical' process. It is not just about "how we SEE things", i.e., about discovering a new map of the territory - what we call "constructivism", or popularly known as "consciousness". Within such an epistemology, the enlightened individual always remains an 'ego in the centre', busily constructing the world in their mind. It is also about a phenomenological "being-in-relation" with the world, about being pulled into the world. That disruptive pointer is not innocuous. It carries the irritating demand of the world not to lead, but to follow - to step responsibly into my fullest freedom. It seeks to enable an organisation or individual to learn "how to BECOME ", growing their innate capacity to act, contribute to, and step into the aliveness of their lifeworld. The gesture of a good leader, much like a good teacher, calls me to look out to the world, and for the world. Such an existential request can ever only work as a gift - it manifests its charism when it arrives without chains of command or control attached. When it reveals itself as a transcendental "us", the primordial energy of life…

Back to that initial story of the leader climbing the ladder. It provides a seductively simple image. And for many years it has shaped my thinking about what it means - and what is expected of me - to be a good leader. But it is not the only way to look at leadership and we must carefully explore other stories, even those that do not frequently get told, because they might be more complicated and less compelling.

In this context, I recall being in a meeting at the Institute of Directors in London with Nigel Farage, pre-Brexit. After an hour into his talk I was both hugely impressed and utterly frightened by the brilliant simplicity of his arguments to leave the EU. His reasons were utterly flawed, even deceitful, but nevertheless powerful and persuasive. The room was boiling with energy! In comparison, all the necessary counterarguments I could think of- albeit more truthful and accurate - sounded dry, complicated and lifeless. And as we know, the Brexiteers won. Narratives are powerful, even when they are wrong.

Maybe we must purposefully re-examine our accumulated truths, stories and favourite quotes once in a while to ensure we are not unwittingly perpetuating an ineffective gospel. On that note, dear Steve, it's time to move on from your forest. But my most sincere thanks go to you, nevertheless! You've provided that initial pointer that made me want to become the 'best leader I could be' and I haven't stopped trying ever since. And I reckon that is truly a story that never ends…

---

COMMENTS & CLARIFICATIONS: Many people came back and suggested that the "pointing of the finger" could be interpreted in many less positive ways, or that Stephen Covey had written a very good book and should not be criticised. I reckon herein lies the difficulty, but also the intention, of bringing across different "epistemological paradigms" that are "deconstructed" in the story. The invitation is to "look beyond" the finger, i.e., the story itself, and instead to reflect about where it might point us.

Popular articles in the KnowledgeHub: Good Leadership

.

.