When we “see the world” as a fragmented array of constituents who lay normative claims on the economy, or an Organisation, or the State, we quickly forget that such a perspective is necessarily incomplete. Not only because we often find ourselves in multiple roles but, more importantly, because any aggregation of partial viewpoints could never “add up” to the common good.

The problem with STAKEHOLDER CAPITALISM remains, in my interpretation, primarily ontological.

What does that mean? It means that when we “see the world” as a fragmented array of constituents who lay normative claims on the economy, or an Organisation, or the State, we quickly forget that such a perspective is necessarily incomplete. Not only because we often find ourselves in multiple roles — as employee AND citizen, AND consumer, AND investor — but, more importantly, because any aggregation of such partial agendas and viewpoints could never “add up” to the common good.

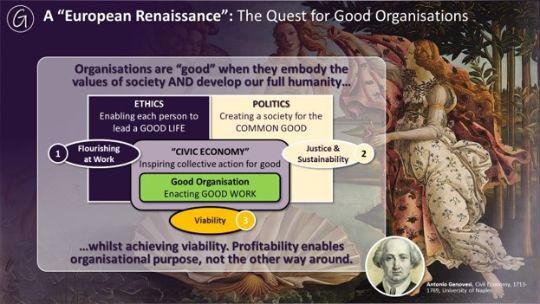

The common good - defined as those characteristics of a society (like justice, peace, systemic trust or freedom) that we can only attain together - instead emerges by way of shifting perspective from our own needs and goods to the system — by stepping from an “ego-logical” and individual into an ecological and inter-relational identity.

(Which explains, by the way, why those excited and angry questions we always receive when we adopt the term ‘common good’ – Defined by whom?! For whom?! Who dares to decide what’s good for me?! Etc – make no sense and simply demonstrate how much an individualist ontology (and ethical egotism) are prevalent today.)

This same “ontological gap” beleaguered the notion of CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) since its inception. As soon as I understand myself and my business as separate to society, and merely seek to define a (minimal) legitimate obligation towards it, I am missing the point. My engagement with the community becomes an act of mere voluntarism and philanthropy. Yet, from a systemic or relational vantage point, our common life on the planet, IS first. (Not: “comes first”, but “is” first — our ‘being in the world’ is “phenomenologically” enmeshed and entangled) The starting point, our “ontology”, is not the individual, but the indivisible whole.

Yet, therein also lies an ethical claim. As Levinas pointed out, our responsibility for a relational “Other” is not ‘derivative, but foundational’. Ethics is the “first philosophy”, inasmuch as “identity” is in itself a relational process of becoming. We come into presence, acquire meaning and gain significance by bringing to life our interdependent relatedness. That is why “integrity” also means “wholeness” — organisations are, by definition, integer organs of society, not stakeholders. That’s a big difference.

Of course, by the same token, any notion of “adjectival capitalism” is, as Henry Mintzberg points out, fatally flawed. It simply isn’t about “adjusting capitalism” — which cements the schism between capital and labour, and between business and state — or about coming up with fancy new attributes (“conscious”, “responsible”, “better” capitalism etc) that somehow seem to imply its critical revision. It is about rethinking our SOCIETY, and the role of our economy, companies, employees — as corporate and private citizen — within it.

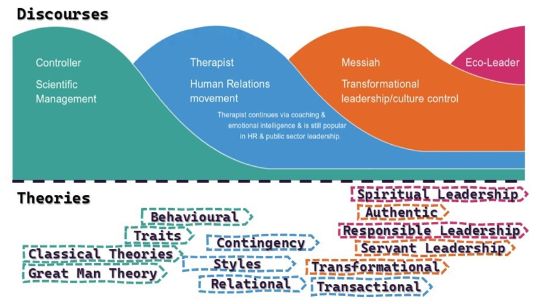

Transformation is always, above all, a shift in perspective and in values — not just a marginal adaptation within a given paradigm. It situates “me” in a new relationship to “the world”. Which makes it much harder to achieve, most of the time…

#transformation #society #business #leadership #stakeholdercapitalism #personaldevelopment

The problem with STAKEHOLDER CAPITALISM remains, in my interpretation, primarily ontological.

What does that mean? It means that when we “see the world” as a fragmented array of constituents who lay normative claims on the economy, or an Organisation, or the State, we quickly forget that such a perspective is necessarily incomplete. Not only because we often find ourselves in multiple roles — as employee AND citizen, AND consumer, AND investor — but, more importantly, because any aggregation of such partial agendas and viewpoints could never “add up” to the common good.

The common good - defined as those characteristics of a society (like justice, peace, systemic trust or freedom) that we can only attain together - instead emerges by way of shifting perspective from our own needs and goods to the system — by stepping from an “ego-logical” and individual into an ecological and inter-relational identity.

(Which explains, by the way, why those excited and angry questions we always receive when we adopt the term ‘common good’ – Defined by whom?! For whom?! Who dares to decide what’s good for me?! Etc – make no sense and simply demonstrate how much an individualist ontology (and ethical egotism) are prevalent today.)

This same “ontological gap” beleaguered the notion of CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) since its inception. As soon as I understand myself and my business as separate to society, and merely seek to define a (minimal) legitimate obligation towards it, I am missing the point. My engagement with the community becomes an act of mere voluntarism and philanthropy. Yet, from a systemic or relational vantage point, our common life on the planet, IS first. (Not: “comes first”, but “is” first — our ‘being in the world’ is “phenomenologically” enmeshed and entangled) The starting point, our “ontology”, is not the individual, but the indivisible whole.

Yet, therein also lies an ethical claim. As Levinas pointed out, our responsibility for a relational “Other” is not ‘derivative, but foundational’. Ethics is the “first philosophy”, inasmuch as “identity” is in itself a relational process of becoming. We come into presence, acquire meaning and gain significance by bringing to life our interdependent relatedness. That is why “integrity” also means “wholeness” — organisations are, by definition, integer organs of society, not stakeholders. That’s a big difference.

Of course, by the same token, any notion of “adjectival capitalism” is, as Henry Mintzberg points out, fatally flawed. It simply isn’t about “adjusting capitalism” — which cements the schism between capital and labour, and between business and state — or about coming up with fancy new attributes (“conscious”, “responsible”, “better” capitalism etc) that somehow seem to imply its critical revision. It is about rethinking our SOCIETY, and the role of our economy, companies, employees — as corporate and private citizen — within it.

Transformation is always, above all, a shift in perspective and in values — not just a marginal adaptation within a given paradigm. It situates “me” in a new relationship to “the world”. Which makes it much harder to achieve, most of the time…

#transformation #society #business #leadership #stakeholdercapitalism #personaldevelopment

Other popular articles in the KnowledgeHub: Business Transformation

.

.