Imagine a society where people interact with trust, solidarity and fraternity. Where welfare is not measured in terms of GDP, but lived in terms of public happiness. Where the economy is virtuous and markets aim at shared prosperity through mutual exchange and generous reciprocity. Where organisations are, first and foremost, positive agents of societal change - creating communities, not commodities. And where work is centred on the integral development of each person, not solely on products…

!["There is no such thing as society! There are individual men and women and there are families. […] And people look to themselves first." (Margaret Thatcher in 1987)](https://cdn.bitrix24.com/b18039987/landing/2fd/2fd428b3feeab25fc8db72a43c870c90/article_economics1b_1x.jpg)

Utopia? Radical socialism?

Far from it, claims Stefano Zamagni, a highly awarded professor of Economics and prolific writer on the responsibility of business. What might read like a reactionary (or visionary) pamphlet is actually three centuries old and the most primordial idea of economics. People often forget, as Stefano points out, that we had markets long before the Anglo-American model of neoliberal capitalism sold out the world.

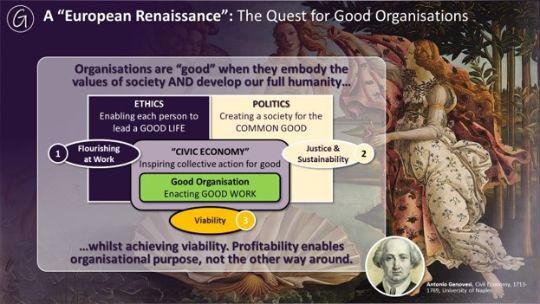

In fact, when Antonio Genovesi in 1754 took on the very first official chair for Economics at the University of Naples, his lectures were centred on a so-called "Civil Economy". Like Adam Smith, Genovesi was both moral philosopher and political economist, and strongly influenced by Aristotelian thought. He viewed economics not as a separate discipline, but as embedded in a system of ethics and economics, politics and theology - all interlinked to achieve "a good life" (in the Aristotelian sense of "eudaimonia" and shared wellbeing). In his work, Genovesi strongly rejected claims of human nature as selfish and instead suggested that "the human capacity for virtue is a crucial ordering device" to mediate between passion and reason, and to help individuals realise their different talents within society. By the same token, virtue and reciprocity are central to the division of labour and the right proportion of different activities in an economy - including a balance between production and trade. Genovesi insisted that it "is a universal law that we cannot make ourselves happy without making others happy". Therefore, a virtuous "love for those with whom we live" is central to attaining common prosperity and the public good - production and market trade are primarily means to efficiently take care of the whole of society, not ways to unduly enrich any one party. This brought questions of societal virtue and vice to the fore of economic thought. In Genovesi's mind, without the shared responsibility of all citizens for the common good and without public trust a society could not develop the taste for civil life and flourish. Notably, public trust was not the aggregation of private trust or a characteristic of the State, but social trust - a unifying "universal sympathy" that binds all citizen together in their quest for the attainment of the good life. Only in such a trusted and well-governed Civil Economy, so his conclusion, would the mutual exchange of different natural faculties support and amplify a human desire for mutual flourishing, and bring common happiness.

So how did we lose that crucial connection between economics and ethics, between society and economy?

Stefano suggests that people are quick to point towards Adam Smith, the alleged grandfather of neoliberal capitalism (who's famous "Wealth of Nations" was by the way published a decade after Genovesi's influential work on the Civil Economy). Yet, for any more-than-cursory reader it is evident that Adam Smith's political philosophy bears little resemblance with today's libertarianism. Albeit often and conveniently ignored, Adam Smith's 'theory of moral sentiments' clearly articulates a need for civic and economic morality, well beyond the individual's self-interest. Whilst Smith argued that once given freedom to produce, people's interest in their own gain would promote greater prosperity, he was far from being an advocate of individual hedonism. Equally influenced by Aristotle, Smith strongly believed that any decent human life required virtues and depended on the respect and love of and for others. Human conduct had always to be in balance between self-interest and the compassion and sympathy for the people around. That said, frustrated with the ineffective bureaucracy during English mercantilism, Smith indeed believed that social forces could much more effectively promote prosocial behaviour than the State, and that legal sanctions were counter-productive to the promotion of virtue. Hence, he might have arrived at some libertarian conclusions, but certainly not in the way most libertarians or inattentive quote hunters do.

But then, we might insist, why did Capitalism prevail?

Here, Prof. Zamagni proposes that economic science and practice has progressively lost its soul. Throughout the centuries, desperately seeking to prove its scientific validity and increasingly enamoured with technical models and theories, economists started to blindly embrace a reductionist and distorted view of humans. Painting a picture of a 'homo economicus' exclusively motivated by selfishness (and much easier to model!), many economists abandoned reflections on ethics and instead put their faith in the "invisible hand" of capitalistic markets. Rational self-interested agents, perfect competition, anonymous producers, full information, a minimum State and no transaction costs - those were the magic ingredients to attain collective utility, so the credo went. And as utility was hard to measure, profit and total production became the celebrated goals.

Sadly, as Stefano points out in his writings, neo-classical economic theories are not only in dire need of a profound axiological requalification, but also enshrine numerous important fallacies that require addressing. The fictious world of standard economics is building on unrealistic anthropological and methodological assumptions and creating massive negative side-effects (our paraphrasing) –

- Economic theory cannot be separated from societal theory. Our economy must take into consideration the well-being of individuals and public happiness.

- There is no justification in economic theory to focus on profits only. Capitalism is merely a "modern feudalism of investors". It is the ownership of patrons. There is no moral principle beyond individual property. Hence, organisations must not be teleopathic in their pursuit of profits, but consider their impact on the wider society. Organisations are above all positive agents of societal change and their ultimate telos is to serve the common good.

- Happiness is not individual self-interest or collective utility, but a mutual form of flourishing that seeks common good. "Total production" or "total good" is not the same as "common good". Following the usual application of methodological individualism in economic science, total good is simply the sum of individual utility. Common good instead is like a multiplicator of individual well-beings. The difference is evident: whilst for total good, distribution does not matter, for common good the failure to cater to even a single agent's wellbeing leads to the product being zero.

- We need contributive justice, as opposed to just distributive justice. Contributive justice relates to the responsibility of each of us to contribute to a civil society, and to our collective well-being. Contributive justice is not absolute but matches a person's obligations with his or her capabilities and role in society.

- Even when free markets are reasonably efficient at allocating resources, efficiency does not guarantee fairness. We might indeed punctually "receive our dinner", referring to the famous quote by Adam Smith, but not our happiness. Our current market system inherently drives to centralisation and empowers the strong over the weak. Moreover, markets systematically underprovide public goods like infrastructure, education, research or investment in sustainability. As Amartya Sen points out, governments needed to focus on capabilities no just on conditions of access.

- We have confounded markets, which is the genus, with capitalism, which is the species. There is no reason to believe that markets should be only focused on transactional exchange, rather than generous reciprocity. And there is no reason - outside the model of perfect competition - to believe that market partners should be anonymous agents, as opposed to "real people". With whom we interact, how and why matters and is fundamental for relational goods to come into existence.

- By the same token, competition does not have to be "creative destruction". The very notion of competition derives from Latin "cum petere", which means to strive together, to engage in a joint enterprise towards a common endeavour. This implies competitive cooperation with each other for a shared purpose, not "positional competition" against one another

- Rationality is not an abstract utilitarian calculus but always a function of reason and judgment. In fact, there are two types of rationality - a utilitarian one, focused on the instrumental optimisation of outcomes, and so-called "expressive rationality" that is acting out on our inner beliefs, emotions and values. The claim that instrumentalism is the most evolved form or rationality is simply preposterous.

- Globalisation has made things worse and increased the gap between winners and losers. Big companies can pursue opportunities independent of national governments and without accountability to the people in countries where their profit is made.

"Today, we have come to the point where even the most 'abstract' of economists cannot but admit that if we want to attack the almost totally new problems of our society - such as the endemic aggravation of inequality, the scandal of human hunger, the emergence of new social pathologies, the rise of clashes of identity in addition to the traditional clash of interests, the paradoxes of happiness, unsustainable development, and so on - research simply can no longer confine itself to a sort of anthropological limbo". Unfortunately, "Many Business Schools are obsolete."

What Stefano does not say is that such theories might have well played into the hands of the ruling elites and still do. In a society that promotes everybody to become a mini-capitalist, constantly self-optimising our marketability rather than taking interest in the system as a whole, fragmentation is persistent, the status quo cemented and the market continues to favours the existing holders of wealth and power…

Yet, it must be evident to even its most adamant defenders, that our current capitalistic system is failing.

We produce flatlining happiness, unacceptable imbalances and terrible inequality. As Oxfam states, we are nearing a system where the 1% possess 99% of wealth. And most importantly, we are corrupting ourselves. In this "age of impunity", our social immune system has become deeply compromised. Greed and dishonesty have become a contagious and accepted social disease. We are living in a dangerous society that has fallen prey of the seductions of the marketplace and become addicted to the state to provide care. The former is a hollow substitute for human relationships and the latter dehumanizes its recipients. As a result, our "corporate society" has lost its capacity to generate faith in the future. Behind a compulsive search for wealth and profit, and the craze of instant gratification lies the desperate attempt to fill a gap of meaning that cannot be filled. It is no surprise that our economic troubles coincide with social breakdown and diminished civic participation. Poverty and poverty of mental well-being are a consequence of institutional failure, of the lack of a shared system of values, not technicalities.

So, is there hope? Yes, there is.

We must, Stefano pleads, return to our roots and together re-examine the ideas of the past, whilst asking the questions of our future children. It is a fallacy to believe that markets are "ethically neutral" - they are either ethical, or they are not. Markets that do not produce both value and values are evil. In order to progress, we must regain focus on common well-being, on morality rather than materialism - as part of that important idea of the Civil Economy. We must again cherish the supreme value of every human being and adjust the future of work to the human conditions, not vice versa - then a welfare state becomes unnecessary. We must return from a society of individuals to a civil community of people, reembracing virtuous interdependence whilst discouraging sinful egotism and avarice. And, most importantly, we must rediscover the spirit of reciprocity which is at the basis of social life and public happiness. More than private or public goods, today we need 'relational goods'. Only in relations with others can we discover and develop ourselves… our relationships have more than transactional market value, they are fundamental to our well-being.

Hence, if we want to remediate our fortunes, we cannot continue to hunker down in front of Netflix, or bowl alone in the forums in cyberspace. We must start to take care. Because taking care of each other is central to a society's happiness, not something we can leave to the State after we have dealt with the economy. The truth is simple: our caring relationships ARE the economy!

---

Stefano Zamagni is a renowned and highly awarded Italian Economist, prolific writer and teacher, Professor of Economics at the University of Bologna and Johns Hopkins University, and - amongst many other positions - President of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences.

References (amongst others):

https://www.sofidel.com/en/softandgreen/sustainability-as-a-value/what-is-civil-economy-interview-with-stefano-zamagni/

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/smith-moral-political/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09672567.2018.1487462?journalCode=rejh20

For our full Leaders for Humanity interview with Stefano Zamagni see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8mHjq-gEK0&list=PLAPiHnsKsNHvIX9ScwluwGVsMH8DI5z-1&index=8

#UnitedForGood #GoodOrganisations #Leadership #Management #EthicsAndExcellence #Transformation #PersonalDevelopment #Work #LeadersForHumanity

Utopia? Radical socialism?

Far from it, claims Stefano Zamagni, a highly awarded professor of Economics and prolific writer on the responsibility of business. What might read like a reactionary (or visionary) pamphlet is actually three centuries old and the most primordial idea of economics. People often forget, as Stefano points out, that we had markets long before the Anglo-American model of neoliberal capitalism sold out the world.

In fact, when Antonio Genovesi in 1754 took on the very first official chair for Economics at the University of Naples, his lectures were centred on a so-called "Civil Economy". Like Adam Smith, Genovesi was both moral philosopher and political economist, and strongly influenced by Aristotelian thought. He viewed economics not as a separate discipline, but as embedded in a system of ethics and economics, politics and theology - all interlinked to achieve "a good life" (in the Aristotelian sense of "eudaimonia" and shared wellbeing). In his work, Genovesi strongly rejected claims of human nature as selfish and instead suggested that "the human capacity for virtue is a crucial ordering device" to mediate between passion and reason, and to help individuals realise their different talents within society. By the same token, virtue and reciprocity are central to the division of labour and the right proportion of different activities in an economy - including a balance between production and trade. Genovesi insisted that it "is a universal law that we cannot make ourselves happy without making others happy". Therefore, a virtuous "love for those with whom we live" is central to attaining common prosperity and the public good - production and market trade are primarily means to efficiently take care of the whole of society, not ways to unduly enrich any one party. This brought questions of societal virtue and vice to the fore of economic thought. In Genovesi's mind, without the shared responsibility of all citizens for the common good and without public trust a society could not develop the taste for civil life and flourish. Notably, public trust was not the aggregation of private trust or a characteristic of the State, but social trust - a unifying "universal sympathy" that binds all citizen together in their quest for the attainment of the good life. Only in such a trusted and well-governed Civil Economy, so his conclusion, would the mutual exchange of different natural faculties support and amplify a human desire for mutual flourishing, and bring common happiness.

So how did we lose that crucial connection between economics and ethics, between society and economy?

Stefano suggests that people are quick to point towards Adam Smith, the alleged grandfather of neoliberal capitalism (who's famous "Wealth of Nations" was by the way published a decade after Genovesi's influential work on the Civil Economy). Yet, for any more-than-cursory reader it is evident that Adam Smith's political philosophy bears little resemblance with today's libertarianism. Albeit often and conveniently ignored, Adam Smith's 'theory of moral sentiments' clearly articulates a need for civic and economic morality, well beyond the individual's self-interest. Whilst Smith argued that once given freedom to produce, people's interest in their own gain would promote greater prosperity, he was far from being an advocate of individual hedonism. Equally influenced by Aristotle, Smith strongly believed that any decent human life required virtues and depended on the respect and love of and for others. Human conduct had always to be in balance between self-interest and the compassion and sympathy for the people around. That said, frustrated with the ineffective bureaucracy during English mercantilism, Smith indeed believed that social forces could much more effectively promote prosocial behaviour than the State, and that legal sanctions were counter-productive to the promotion of virtue. Hence, he might have arrived at some libertarian conclusions, but certainly not in the way most libertarians or inattentive quote hunters do.

But then, we might insist, why did Capitalism prevail?

Here, Prof. Zamagni proposes that economic science and practice has progressively lost its soul. Throughout the centuries, desperately seeking to prove its scientific validity and increasingly enamoured with technical models and theories, economists started to blindly embrace a reductionist and distorted view of humans. Painting a picture of a 'homo economicus' exclusively motivated by selfishness (and much easier to model!), many economists abandoned reflections on ethics and instead put their faith in the "invisible hand" of capitalistic markets. Rational self-interested agents, perfect competition, anonymous producers, full information, a minimum State and no transaction costs - those were the magic ingredients to attain collective utility, so the credo went. And as utility was hard to measure, profit and total production became the celebrated goals.

Sadly, as Stefano points out in his writings, neo-classical economic theories are not only in dire need of a profound axiological requalification, but also enshrine numerous important fallacies that require addressing. The fictious world of standard economics is building on unrealistic anthropological and methodological assumptions and creating massive negative side-effects (our paraphrasing) –

- Economic theory cannot be separated from societal theory. Our economy must take into consideration the well-being of individuals and public happiness.

- There is no justification in economic theory to focus on profits only. Capitalism is merely a "modern feudalism of investors". It is the ownership of patrons. There is no moral principle beyond individual property. Hence, organisations must not be teleopathic in their pursuit of profits, but consider their impact on the wider society. Organisations are above all positive agents of societal change and their ultimate telos is to serve the common good.

- Happiness is not individual self-interest or collective utility, but a mutual form of flourishing that seeks common good. "Total production" or "total good" is not the same as "common good". Following the usual application of methodological individualism in economic science, total good is simply the sum of individual utility. Common good instead is like a multiplicator of individual well-beings. The difference is evident: whilst for total good, distribution does not matter, for common good the failure to cater to even a single agent's wellbeing leads to the product being zero.

- We need contributive justice, as opposed to just distributive justice. Contributive justice relates to the responsibility of each of us to contribute to a civil society, and to our collective well-being. Contributive justice is not absolute but matches a person's obligations with his or her capabilities and role in society.

- Even when free markets are reasonably efficient at allocating resources, efficiency does not guarantee fairness. We might indeed punctually "receive our dinner", referring to the famous quote by Adam Smith, but not our happiness. Our current market system inherently drives to centralisation and empowers the strong over the weak. Moreover, markets systematically underprovide public goods like infrastructure, education, research or investment in sustainability. As Amartya Sen points out, governments needed to focus on capabilities no just on conditions of access.

- We have confounded markets, which is the genus, with capitalism, which is the species. There is no reason to believe that markets should be only focused on transactional exchange, rather than generous reciprocity. And there is no reason - outside the model of perfect competition - to believe that market partners should be anonymous agents, as opposed to "real people". With whom we interact, how and why matters and is fundamental for relational goods to come into existence.

- By the same token, competition does not have to be "creative destruction". The very notion of competition derives from Latin "cum petere", which means to strive together, to engage in a joint enterprise towards a common endeavour. This implies competitive cooperation with each other for a shared purpose, not "positional competition" against one another

- Rationality is not an abstract utilitarian calculus but always a function of reason and judgment. In fact, there are two types of rationality - a utilitarian one, focused on the instrumental optimisation of outcomes, and so-called "expressive rationality" that is acting out on our inner beliefs, emotions and values. The claim that instrumentalism is the most evolved form or rationality is simply preposterous.

- Globalisation has made things worse and increased the gap between winners and losers. Big companies can pursue opportunities independent of national governments and without accountability to the people in countries where their profit is made.

"Today, we have come to the point where even the most 'abstract' of economists cannot but admit that if we want to attack the almost totally new problems of our society - such as the endemic aggravation of inequality, the scandal of human hunger, the emergence of new social pathologies, the rise of clashes of identity in addition to the traditional clash of interests, the paradoxes of happiness, unsustainable development, and so on - research simply can no longer confine itself to a sort of anthropological limbo". Unfortunately, "Many Business Schools are obsolete."

What Stefano does not say is that such theories might have well played into the hands of the ruling elites and still do. In a society that promotes everybody to become a mini-capitalist, constantly self-optimising our marketability rather than taking interest in the system as a whole, fragmentation is persistent, the status quo cemented and the market continues to favours the existing holders of wealth and power…

Yet, it must be evident to even its most adamant defenders, that our current capitalistic system is failing.

We produce flatlining happiness, unacceptable imbalances and terrible inequality. As Oxfam states, we are nearing a system where the 1% possess 99% of wealth. And most importantly, we are corrupting ourselves. In this "age of impunity", our social immune system has become deeply compromised. Greed and dishonesty have become a contagious and accepted social disease. We are living in a dangerous society that has fallen prey of the seductions of the marketplace and become addicted to the state to provide care. The former is a hollow substitute for human relationships and the latter dehumanizes its recipients. As a result, our "corporate society" has lost its capacity to generate faith in the future. Behind a compulsive search for wealth and profit, and the craze of instant gratification lies the desperate attempt to fill a gap of meaning that cannot be filled. It is no surprise that our economic troubles coincide with social breakdown and diminished civic participation. Poverty and poverty of mental well-being are a consequence of institutional failure, of the lack of a shared system of values, not technicalities.

So, is there hope? Yes, there is.

We must, Stefano pleads, return to our roots and together re-examine the ideas of the past, whilst asking the questions of our future children. It is a fallacy to believe that markets are "ethically neutral" - they are either ethical, or they are not. Markets that do not produce both value and values are evil. In order to progress, we must regain focus on common well-being, on morality rather than materialism - as part of that important idea of the Civil Economy. We must again cherish the supreme value of every human being and adjust the future of work to the human conditions, not vice versa - then a welfare state becomes unnecessary. We must return from a society of individuals to a civil community of people, reembracing virtuous interdependence whilst discouraging sinful egotism and avarice. And, most importantly, we must rediscover the spirit of reciprocity which is at the basis of social life and public happiness. More than private or public goods, today we need 'relational goods'. Only in relations with others can we discover and develop ourselves… our relationships have more than transactional market value, they are fundamental to our well-being.

Hence, if we want to remediate our fortunes, we cannot continue to hunker down in front of Netflix, or bowl alone in the forums in cyberspace. We must start to take care. Because taking care of each other is central to a society's happiness, not something we can leave to the State after we have dealt with the economy. The truth is simple: our caring relationships ARE the economy!

---

Stefano Zamagni is a renowned and highly awarded Italian Economist, prolific writer and teacher, Professor of Economics at the University of Bologna and Johns Hopkins University, and - amongst many other positions - President of the Pontifical Academy of Social Sciences.

References (amongst others):

https://www.sofidel.com/en/softandgreen/sustainability-as-a-value/what-is-civil-economy-interview-with-stefano-zamagni/

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/smith-moral-political/

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09672567.2018.1487462?journalCode=rejh20

For our full Leaders for Humanity interview with Stefano Zamagni see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8mHjq-gEK0&list=PLAPiHnsKsNHvIX9ScwluwGVsMH8DI5z-1&index=8

#UnitedForGood #GoodOrganisations #Leadership #Management #EthicsAndExcellence #Transformation #PersonalDevelopment #Work #LeadersForHumanity

Other popular articles in the KnowledgeHub: Good Economy

.

.