Why there is and never will be a Nobel Prize in Economics and how the a bogus prize awarded by the Swedish Central Bank has done probably more harm than good. An investigative drama in three acts...

Prologue

It all starts on the chilly morning of Wednesday, November 27th 1895, in 242 Rue de Rivoli, at the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris. Not far away the famous clock at the Conciergerie strikes 9 o' clock. Alfred Nobel, the Swedish chemist, engineer, inventor and businessman is about to bequeath his massive fortune of 31 million Swedish kronor (472 million dollars in 2012) to establish a series of honorary prizes. We might imagine the following conversation with a family lawyer to assemble the final details of his will…

Act 1: There Shall Be No Nobel Prize in Economics

Alfred Nobel is seated comfortably at his regular table in the corner of Svenska Klubben's massive salon, overlooking the almost winterly Jardin des Tuileries. Morning traffic is clogging the arteries of the capital and from Place de la Concorde arrives the usual hustle and bustle, but Alfred's mind is deeply lost in thought. Whilst his entrepreneurial career had endowed him with significant affluence, it had not endeared him to the public. His most famous invention was dynamite, an explosive made of nitroglycerin patented in 1867, and his family owned a major manufacturer of cannons and other armaments. When his brother Ludvig had died a few years earlier, several newspapers mistakenly published his own obituary, scolding him harshly for the invention of military devices. Headlines had read: The "merchant of death is dead: Dr. Alfred Nobel, who became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before, died yesterday…" The almost universal reproof had stirred Alfred deeply. Now 62 years old and feeling his life coming to an end, he was committed to leave behind a positive legacy.

Prologue

It all starts on the chilly morning of Wednesday, November 27th 1895, in 242 Rue de Rivoli, at the Swedish-Norwegian Club in Paris. Not far away the famous clock at the Conciergerie strikes 9 o' clock. Alfred Nobel, the Swedish chemist, engineer, inventor and businessman is about to bequeath his massive fortune of 31 million Swedish kronor (472 million dollars in 2012) to establish a series of honorary prizes. We might imagine the following conversation with a family lawyer to assemble the final details of his will…

Act 1: There Shall Be No Nobel Prize in Economics

Alfred Nobel is seated comfortably at his regular table in the corner of Svenska Klubben's massive salon, overlooking the almost winterly Jardin des Tuileries. Morning traffic is clogging the arteries of the capital and from Place de la Concorde arrives the usual hustle and bustle, but Alfred's mind is deeply lost in thought. Whilst his entrepreneurial career had endowed him with significant affluence, it had not endeared him to the public. His most famous invention was dynamite, an explosive made of nitroglycerin patented in 1867, and his family owned a major manufacturer of cannons and other armaments. When his brother Ludvig had died a few years earlier, several newspapers mistakenly published his own obituary, scolding him harshly for the invention of military devices. Headlines had read: The "merchant of death is dead: Dr. Alfred Nobel, who became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before, died yesterday…" The almost universal reproof had stirred Alfred deeply. Now 62 years old and feeling his life coming to an end, he was committed to leave behind a positive legacy.

At this moment his lawyer appears and settles himself smoothly on the chair opposite him, interrupting Alfred's stream of consciousness. Greeting him with a broad smile, the lawyer immediately produces pen and paper - with his all-so-familiar proficiency, and gets ready to discuss the final adjustments to the testament.

Lawyer: So, Alfred, what exactly is the goal of these awards you have in mind?

Alfred: I have a vision of a better world. I believe that people are capable of helping to improve society through knowledge, science and humanism. I want to create a prize that rewards those discoveries that confer the greatest benefit to humankind.

Lawyer, busily taking notes: Very good. And which disciplines shall the award include?

Alfred, pondering: Physics and chemistry for sure!

Lawyer, nodding: Yes.

Alfred: Physiology or medicine.

Lawyer: Perfekt.

Alfred: Literature?

Lawyer: Why not.

Alfred: But it should be in "an ideal direction". And, of course, something with peace.

Lawyer: Elementary, dear Alfred. Let me suggest the following.

He reads from his notes: I herewith establish two prizes for eminence in physical science and chemistry, to be chosen by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences; moreover, a prize for medical science or physiology; another one for literary works; and a final prize to be given to the person or society that renders the greatest service to the cause of international fraternity, in the suppression or reduction of standing armies, or in the establishment or furtherance of peace congresses.

Alfred: Excellent. And no consideration shall be given to nationality.

After a pause: What about… economics?

His suggestion is met by the stern frown of his lawyer.

Alfred, teasingly: Nej?

Lawyer, determined not to lose his well-studied air of judicious indifference: Surely, you must be joking, dear Alfred?

Both laugh for a long time.

We can only fantasize whether and how such a dialogue could ever have happened, but we know for certain whither it led. Since 1901, Nobel Prizes have been awarded 609 times to 975 people and 25 organizations. Each Nobel Prize consists of a gold medal, a diploma bearing a citation, and a sum of money - the amount depending on the income of Alfred Nobel's Foundation. In 2022, the amount was set at 10 million Swedish kronor per full Nobel Prize (roughly one million dollars). Throughout their impressive history, Nobel Prizes have inspired generations of scientists and promoted a humanistic agenda - occasionally provoking temperamental eruptions of public opinion around the globe (Peace Prize for Obama, anyone?). Without doubt, Alfred Nobel posthumously succeeded in adding yet another explosive invention to his track record.

Act 2: Money Makes the World Go Round

Hold it! - You might chip in - Economics never made it into the Nobel Prize categories? Really?! But there is a "Nobel Prize in Economics", isn't there?

In short: no, there isn't. But, as always, whenever someone with a big ego, strong will and a stash of cash arrives… the story gets murky. To understand exactly what happened we must travel back in time once again.

It is another Wednesday, the 15th of May 1968 to be precise, and we are right in the centre of Sweden's capital, Stockholm - Alfred Nobel's home town. More than 60 years after the first Nobel Prize was celebrated here, we are hurrying over Norrbro bridge to reach the snug island of Helgeandsholmen where Sweden's Riksbank - the "world's oldest central bank" - is occupying an emblematic neo-classical and semi-circular building (today part of Parliament House). Three days of festivities to honour the Bank's tercentenary anniversary are starting today and the street is overflowing with central bank managers and guests from all over the world. To kick things off in style, the Riksbank just issued a 10 kronor banknote commemorating itself… we might imagine a truly remarkable celebration is about to begin.

At this moment his lawyer appears and settles himself smoothly on the chair opposite him, interrupting Alfred's stream of consciousness. Greeting him with a broad smile, the lawyer immediately produces pen and paper - with his all-so-familiar proficiency, and gets ready to discuss the final adjustments to the testament.

Lawyer: So, Alfred, what exactly is the goal of these awards you have in mind?

Alfred: I have a vision of a better world. I believe that people are capable of helping to improve society through knowledge, science and humanism. I want to create a prize that rewards those discoveries that confer the greatest benefit to humankind.

Lawyer, busily taking notes: Very good. And which disciplines shall the award include?

Alfred, pondering: Physics and chemistry for sure!

Lawyer, nodding: Yes.

Alfred: Physiology or medicine.

Lawyer: Perfekt.

Alfred: Literature?

Lawyer: Why not.

Alfred: But it should be in "an ideal direction". And, of course, something with peace.

Lawyer: Elementary, dear Alfred. Let me suggest the following.

He reads from his notes: I herewith establish two prizes for eminence in physical science and chemistry, to be chosen by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences; moreover, a prize for medical science or physiology; another one for literary works; and a final prize to be given to the person or society that renders the greatest service to the cause of international fraternity, in the suppression or reduction of standing armies, or in the establishment or furtherance of peace congresses.

Alfred: Excellent. And no consideration shall be given to nationality.

After a pause: What about… economics?

His suggestion is met by the stern frown of his lawyer.

Alfred, teasingly: Nej?

Lawyer, determined not to lose his well-studied air of judicious indifference: Surely, you must be joking, dear Alfred?

Both laugh for a long time.

We can only fantasize whether and how such a dialogue could ever have happened, but we know for certain whither it led. Since 1901, Nobel Prizes have been awarded 609 times to 975 people and 25 organizations. Each Nobel Prize consists of a gold medal, a diploma bearing a citation, and a sum of money - the amount depending on the income of Alfred Nobel's Foundation. In 2022, the amount was set at 10 million Swedish kronor per full Nobel Prize (roughly one million dollars). Throughout their impressive history, Nobel Prizes have inspired generations of scientists and promoted a humanistic agenda - occasionally provoking temperamental eruptions of public opinion around the globe (Peace Prize for Obama, anyone?). Without doubt, Alfred Nobel posthumously succeeded in adding yet another explosive invention to his track record.

Act 2: Money Makes the World Go Round

Hold it! - You might chip in - Economics never made it into the Nobel Prize categories? Really?! But there is a "Nobel Prize in Economics", isn't there?

In short: no, there isn't. But, as always, whenever someone with a big ego, strong will and a stash of cash arrives… the story gets murky. To understand exactly what happened we must travel back in time once again.

It is another Wednesday, the 15th of May 1968 to be precise, and we are right in the centre of Sweden's capital, Stockholm - Alfred Nobel's home town. More than 60 years after the first Nobel Prize was celebrated here, we are hurrying over Norrbro bridge to reach the snug island of Helgeandsholmen where Sweden's Riksbank - the "world's oldest central bank" - is occupying an emblematic neo-classical and semi-circular building (today part of Parliament House). Three days of festivities to honour the Bank's tercentenary anniversary are starting today and the street is overflowing with central bank managers and guests from all over the world. To kick things off in style, the Riksbank just issued a 10 kronor banknote commemorating itself… we might imagine a truly remarkable celebration is about to begin.

10 Kronor banknote commemorating the Bank's 300th anniversary (Source: Internet)

What exactly happened during the Bank's 300th birthday party, of course we cannot know. Maybe one of the many attending central bankers just had a "brilliant" idea. Or, perhaps some upstart treasurer, exorbitant after a few glasses too many of Gula Änkan, made a practical joke, proclaiming bumptiously that money indeed DOES buy everything -so why not buy a dead man's homonymous award? Or possibly two of those banking godfathers secretively got together and made a momentous 1 Kronor bet - like the Dukes in Eddy Murphy's Trading Places - to wager that they could turn a humanitarian award into a marketing machine for economic liberalism and have the public pay for it.

Be it as it may, at some point during its jubilee the Swedish Central Bank made the Alfred Nobel Foundation an offer simply too good to refuse: in return for a sixth Nobel prize (in Economics), Sveriges Riksbank promised a large sum of money as an endowment "in perpetuity", adding a generous annual grant of 6.5 million Swedish kronor for "administrative expenses" and 1 million Swedish kronor (until the end of 2008) to include information about the new award on the Nobel Foundation's web site.

I hear you. It all sounds a bit like Judas offering to cover the tab at Jesus's Last Supper, but maybe if you are a central banker with vaults full of cash, well, a conflict of interest might seem just a minor detail. And, as George Washington once quipped, few men have virtue to withstand the highest bidder. The Guardian suggests in a later analysis that the Economics "Nobel prize" came out of a longstanding social conflict: "On one side, central banks and the better-off striving to keep property intact and prices stable; on the other, everyone else's quest for economic security. The Swedish social democratic government clipped the wings of the central bank in pursuit of more housing and jobs. In compensation, the government allowed the bank to keep some funds, which the bank used in 1968 to endow the Nobel Prize in economics as a vanity project to mark its tercentenary." Which, interestingly, makes it the only Prize to be funded by taxpayers.

Unsurprisingly, the Nobel family strongly objected. Peter Nobel, a human rights lawyer and great-grandnephew of Ludvig Nobel, accused the Foundation for misusing his family's name, and stated that no member of the Nobel family ever had any intention to establish a Prize in economics. He suggested that "Nobel despised people who cared more about profits than society's well-being", saying that "there is nothing to indicate that he would have wanted such a prize", and that the association with the Nobel prizes is "a PR coup by economists to improve their reputation".

Others also protested. According to Samuel Brittan of the Financial Times, both former Swedish minister of finance (Kjell-Olof Feldt) and Swedish former minister of commerce (Gunnar Myrdal) wanted the prize abolished. Even Friedrich Hayek, in his famous acceptance speech six years later, stated that had he been consulted on the establishment of a Nobel Prize in economics, he would "have decidedly advised against it". He said: "The Nobel Prize confers on an individual an authority which in economics no man ought to possess. … This does not matter in the natural sciences. Here the influence exercised by an individual is chiefly an influence on his fellow experts; and they will soon cut him down to size if he exceeds his competence. But the influence of the economist that mainly matters is an influence over laymen: politicians, journalists, civil servants and the public generally."

Which of course points to a more principal challenge: "The problem is not so much that there is a Nobel prize in economics, but that there are no equivalent prizes in psychology, sociology, anthropology. Economics, this seems to say, is not a social science but an exact one, like physics or chemistry - a distinction that not only encourages hubris among economists but also changes the way we think about the economy".

Undoubtedly these were all important arguments, but to cut a long story short, the Bank prevailed. The "Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel", as it was eventually called, was born - henceforth, you already guessed it, publicly referred to mostly as a "Nobel Prize in Economics".

Act 3: Tainted Laurels – Fifty Years of Not-so-noble Nobel Prizes in Economics

Fine - you might concede - but at the end of the day, what's in a name?! If indeed the Prize did "improve society through knowledge, science and humanism" and rewarded those discoveries that "confer the greatest benefit to humankind" its problematic infancy might not matter much.

Perhaps then it is an important question whether the Economics "Nobel" Prize did live up to its noble association and managed to reassure its initial sceptics. Therefore, let us briefly examine how winners were selected, who those winners were, and, finally, which "discoveries" the winners promoted to make the world better.

Scene 1. A Rather Insular Selection Process

One condition for the new Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences was that all winners would be chosen in "a similar way" to other Nobel Prize recipients. So how does the selection process work?

10 Kronor banknote commemorating the Bank's 300th anniversary (Source: Internet)

What exactly happened during the Bank's 300th birthday party, of course we cannot know. Maybe one of the many attending central bankers just had a "brilliant" idea. Or, perhaps some upstart treasurer, exorbitant after a few glasses too many of Gula Änkan, made a practical joke, proclaiming bumptiously that money indeed DOES buy everything -so why not buy a dead man's homonymous award? Or possibly two of those banking godfathers secretively got together and made a momentous 1 Kronor bet - like the Dukes in Eddy Murphy's Trading Places - to wager that they could turn a humanitarian award into a marketing machine for economic liberalism and have the public pay for it.

Be it as it may, at some point during its jubilee the Swedish Central Bank made the Alfred Nobel Foundation an offer simply too good to refuse: in return for a sixth Nobel prize (in Economics), Sveriges Riksbank promised a large sum of money as an endowment "in perpetuity", adding a generous annual grant of 6.5 million Swedish kronor for "administrative expenses" and 1 million Swedish kronor (until the end of 2008) to include information about the new award on the Nobel Foundation's web site.

I hear you. It all sounds a bit like Judas offering to cover the tab at Jesus's Last Supper, but maybe if you are a central banker with vaults full of cash, well, a conflict of interest might seem just a minor detail. And, as George Washington once quipped, few men have virtue to withstand the highest bidder. The Guardian suggests in a later analysis that the Economics "Nobel prize" came out of a longstanding social conflict: "On one side, central banks and the better-off striving to keep property intact and prices stable; on the other, everyone else's quest for economic security. The Swedish social democratic government clipped the wings of the central bank in pursuit of more housing and jobs. In compensation, the government allowed the bank to keep some funds, which the bank used in 1968 to endow the Nobel Prize in economics as a vanity project to mark its tercentenary." Which, interestingly, makes it the only Prize to be funded by taxpayers.

Unsurprisingly, the Nobel family strongly objected. Peter Nobel, a human rights lawyer and great-grandnephew of Ludvig Nobel, accused the Foundation for misusing his family's name, and stated that no member of the Nobel family ever had any intention to establish a Prize in economics. He suggested that "Nobel despised people who cared more about profits than society's well-being", saying that "there is nothing to indicate that he would have wanted such a prize", and that the association with the Nobel prizes is "a PR coup by economists to improve their reputation".

Others also protested. According to Samuel Brittan of the Financial Times, both former Swedish minister of finance (Kjell-Olof Feldt) and Swedish former minister of commerce (Gunnar Myrdal) wanted the prize abolished. Even Friedrich Hayek, in his famous acceptance speech six years later, stated that had he been consulted on the establishment of a Nobel Prize in economics, he would "have decidedly advised against it". He said: "The Nobel Prize confers on an individual an authority which in economics no man ought to possess. … This does not matter in the natural sciences. Here the influence exercised by an individual is chiefly an influence on his fellow experts; and they will soon cut him down to size if he exceeds his competence. But the influence of the economist that mainly matters is an influence over laymen: politicians, journalists, civil servants and the public generally."

Which of course points to a more principal challenge: "The problem is not so much that there is a Nobel prize in economics, but that there are no equivalent prizes in psychology, sociology, anthropology. Economics, this seems to say, is not a social science but an exact one, like physics or chemistry - a distinction that not only encourages hubris among economists but also changes the way we think about the economy".

Undoubtedly these were all important arguments, but to cut a long story short, the Bank prevailed. The "Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel", as it was eventually called, was born - henceforth, you already guessed it, publicly referred to mostly as a "Nobel Prize in Economics".

Act 3: Tainted Laurels – Fifty Years of Not-so-noble Nobel Prizes in Economics

Fine - you might concede - but at the end of the day, what's in a name?! If indeed the Prize did "improve society through knowledge, science and humanism" and rewarded those discoveries that "confer the greatest benefit to humankind" its problematic infancy might not matter much.

Perhaps then it is an important question whether the Economics "Nobel" Prize did live up to its noble association and managed to reassure its initial sceptics. Therefore, let us briefly examine how winners were selected, who those winners were, and, finally, which "discoveries" the winners promoted to make the world better.

Scene 1. A Rather Insular Selection Process

One condition for the new Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences was that all winners would be chosen in "a similar way" to other Nobel Prize recipients. So how does the selection process work?

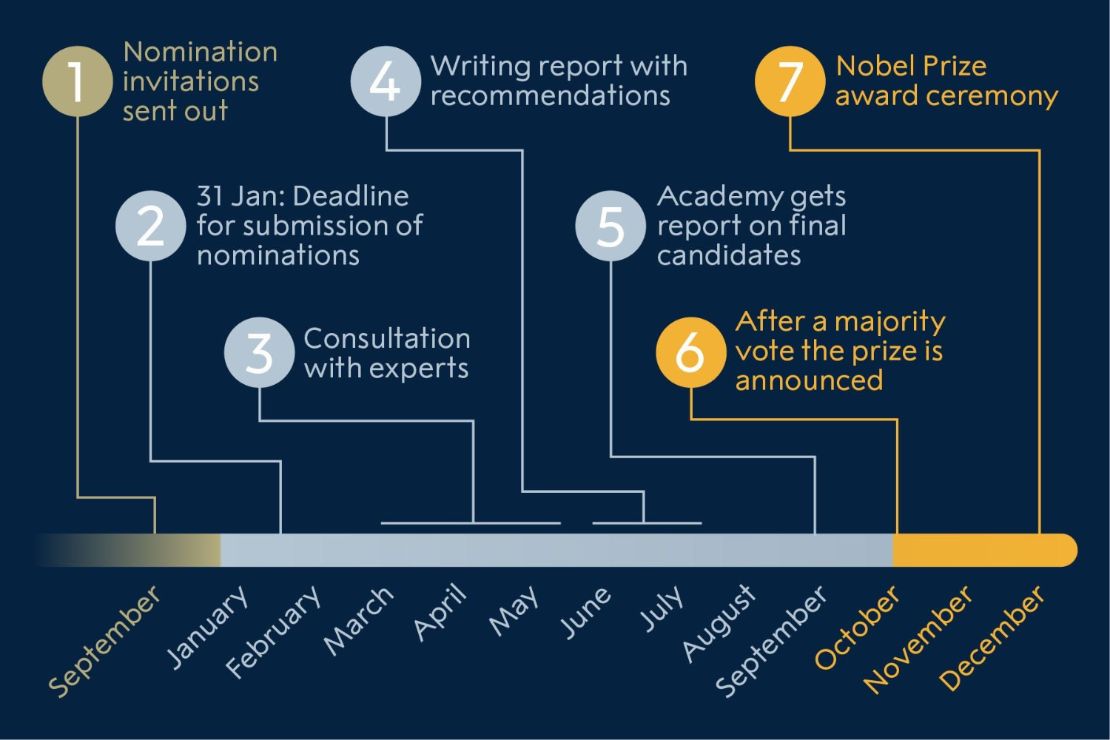

The Nobel Foundation's website suggests that each September the Economics Prize Committee, consisting of five elected members from the Royal Swedish Academy of Science (RSAS), sends invitations to "thousands of scientists, members of academies and university professors in numerous countries", asking them to nominate candidates for the Prize in the coming year. In practice, letters go to Swedish or foreign member of the RSAS; members of the Prize Committee of that year; past laureates; permanent professors of relevant subjects in Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, Finland and Norway. Full stop - nominations are by invitation only.

All incoming proposals are then reviewed by the Prize Committee and preliminary candidates are sent to "specially appointed experts" for independent assessments. Subsequently, the Prize Committee prepares a report, including its recommendations on final candidates. Based on this, all members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences vote in mid-October to determine the next laureate. Laureates receive their Prizes at the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony, which takes place on December 10th (the anniversary of Alfred Nobel's death) each year. Information about Prize nominations cannot be disclosed publicly for 50 years.

In a nutshell, the selection of appointees is a highly sophisticated process, but limited in reach and profoundly untransparent. Proposals appear to be made by a small and mostly euro-centric set of academics, plus previous Prize winners, who all choose nominations mainly among their own peers.

Scene 2. The Good Old Boys' Club of Economics Laureates

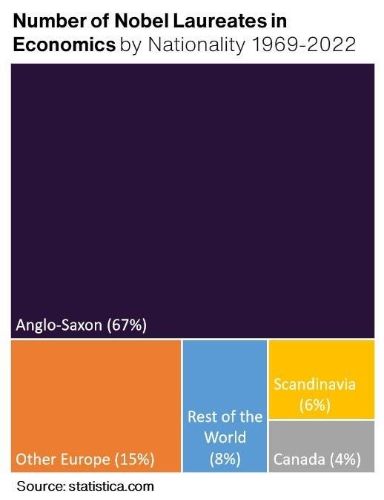

Since its inception the Economics Prize has been awarded 54 times to 92 laureates between 1969 and 2022. So, who got all those awards?

The Nobel Foundation's website suggests that each September the Economics Prize Committee, consisting of five elected members from the Royal Swedish Academy of Science (RSAS), sends invitations to "thousands of scientists, members of academies and university professors in numerous countries", asking them to nominate candidates for the Prize in the coming year. In practice, letters go to Swedish or foreign member of the RSAS; members of the Prize Committee of that year; past laureates; permanent professors of relevant subjects in Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, Finland and Norway. Full stop - nominations are by invitation only.

All incoming proposals are then reviewed by the Prize Committee and preliminary candidates are sent to "specially appointed experts" for independent assessments. Subsequently, the Prize Committee prepares a report, including its recommendations on final candidates. Based on this, all members of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences vote in mid-October to determine the next laureate. Laureates receive their Prizes at the Nobel Prize Award Ceremony, which takes place on December 10th (the anniversary of Alfred Nobel's death) each year. Information about Prize nominations cannot be disclosed publicly for 50 years.

In a nutshell, the selection of appointees is a highly sophisticated process, but limited in reach and profoundly untransparent. Proposals appear to be made by a small and mostly euro-centric set of academics, plus previous Prize winners, who all choose nominations mainly among their own peers.

Scene 2. The Good Old Boys' Club of Economics Laureates

Since its inception the Economics Prize has been awarded 54 times to 92 laureates between 1969 and 2022. So, who got all those awards?

The first award in 1969 went to Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen and Norwegian economist Ragnar Frisch "for having developed and applied dynamic models for the analysis of economic processes". Since then, most economics laureates have been white American men aged over 55.

In terms of gender diversity, laureates count only two women among them: Elinor Ostrom, who won in 2009, and Esther Duflo, in 2019. (Note: This roughly corresponds to its "bigger sister" award - across Nobel Prizes, women have taken home just 22 awards, about 3% of the total). Duflo, at 47, is also the youngest ever winner in the field. In terms of nationality overall, 67% of Prize winners are Anglo-Saxon. Sir Arthur Lewis is still the only black Nobel laureate in economics - and he won the Prize 44 years ago.

An analysis by the Daily Star and others points to further worrying biases:

a) Affiliation biases. Paul Samuelson (1970) was the first person from the USA to win the Prize. His PhD supervisor Wassily Leontief (1973) also won the Prize. And so did Leontief's other PhD students - Robert Solow (1987), Vernon Smith (2002), and Thomas Schelling (2005) - as well as Samuelson's PhD students Lawrence Klein (1980) and Robert Merton (1997). Except for Vernon (so far), each of Leontief's students have PhD students who also won the Prize.

b) Mainstream bias. Beyond such and similar clusters, there is a clear tendency to award proponents of neoclassical free market economics. In fact, very few critics of classical economics or economists outside the mainstream have won a Prize. The University of Chicago, famous for championing a free market ideology and spearheaded by Milton Friedman (laureate in 1976), boasts the highest number of winners with over 30 laureates having Chicago as alma mater or serving there at the time of the Prize declaration. Relatedly, it has been noted that several members of the awarding committee have been affiliated with the Mont Pelerin Society.

c) Theory bias. About half of Nobel economists are pure theorists who do not even attempt to confront theory with reality, or verify that their theoretical work improves the world in practice.

Scene 3. The Business of Business is Business

The ideological biases become even more evident when we look more closely at the basic economic theory and values that have been supported by most mainstream economists - and promoted by the Prize winners- over the last five decades.

Paul Samuelson, the second economist to earn the award, sums up neoclassical microeconomic theory as the science of "how we choose to use scarce productive resources with alternative uses to meet productive ends". JK Galbraith (probably the greatest economist outside the mainstream who never earned a Prize!) describes the methodological individualism of economic science further as: "people are making decisions on what they will have; firms are deciding how these decisions can best be served. [Classic] Economics studies the behaviour of people so engaged."

Glaringly missing from any such definition is not only an acknowledgement of the embedded nature of the economy within society, but also an appreciation of the emancipative purpose of economics - and the economy - to benefit humankind. Consumption, in the form of marginal utility, is uncritically reified as expression of the "sovereign choice" of free individuals (or citizens in the case of public expenditure); competition in a perfect market is glorified as the vehicle not only for price allocation, but justice; oligopolies are studied, but the increasingly self-interested concentration and abuse of power by big business is ignored; public policy is mainly posited as a vehicle to support full employment and economic growth, not the sustainable well-being of all. Throughout its short history, classical economics has been busily promoting endless variations of technical sophistries - zealous to appear like a "hard science", whilst dismally failing to progress any deeper moral inquiry.

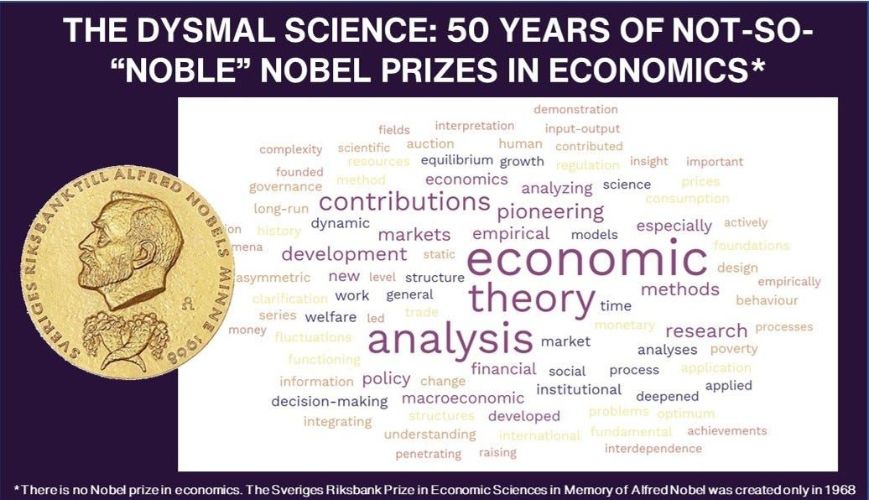

Along that same line, Avner Offer and Gabriel Söderberg analyse the award's history in their book, The Nobel Factor: The Prize in Economics, Social Democracy, and the Market Turn. According to the authors, the Prize clearly favours Economics as a doctrine focused on people's individual interactions with free markets, drawing heavily on abstract theory, mathematical models, and the assumption that people will act in rational self-interest - rather than a paradigm that situates the economy inside society and requires public policy decisions to further sustainable prosperity for all citizens. This is also evident in the word cloud visualising recurrences of themes across motivations for all past awards (based on Nobel Foundation website). Words like "theory", "analysis", and "market" dominate - whilst "human" or "poverty" or "welfare" rarely appear. "Sustainability", "responsibility" or "society" are completely absent.

The first award in 1969 went to Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen and Norwegian economist Ragnar Frisch "for having developed and applied dynamic models for the analysis of economic processes". Since then, most economics laureates have been white American men aged over 55.

In terms of gender diversity, laureates count only two women among them: Elinor Ostrom, who won in 2009, and Esther Duflo, in 2019. (Note: This roughly corresponds to its "bigger sister" award - across Nobel Prizes, women have taken home just 22 awards, about 3% of the total). Duflo, at 47, is also the youngest ever winner in the field. In terms of nationality overall, 67% of Prize winners are Anglo-Saxon. Sir Arthur Lewis is still the only black Nobel laureate in economics - and he won the Prize 44 years ago.

An analysis by the Daily Star and others points to further worrying biases:

a) Affiliation biases. Paul Samuelson (1970) was the first person from the USA to win the Prize. His PhD supervisor Wassily Leontief (1973) also won the Prize. And so did Leontief's other PhD students - Robert Solow (1987), Vernon Smith (2002), and Thomas Schelling (2005) - as well as Samuelson's PhD students Lawrence Klein (1980) and Robert Merton (1997). Except for Vernon (so far), each of Leontief's students have PhD students who also won the Prize.

b) Mainstream bias. Beyond such and similar clusters, there is a clear tendency to award proponents of neoclassical free market economics. In fact, very few critics of classical economics or economists outside the mainstream have won a Prize. The University of Chicago, famous for championing a free market ideology and spearheaded by Milton Friedman (laureate in 1976), boasts the highest number of winners with over 30 laureates having Chicago as alma mater or serving there at the time of the Prize declaration. Relatedly, it has been noted that several members of the awarding committee have been affiliated with the Mont Pelerin Society.

c) Theory bias. About half of Nobel economists are pure theorists who do not even attempt to confront theory with reality, or verify that their theoretical work improves the world in practice.

Scene 3. The Business of Business is Business

The ideological biases become even more evident when we look more closely at the basic economic theory and values that have been supported by most mainstream economists - and promoted by the Prize winners- over the last five decades.

Paul Samuelson, the second economist to earn the award, sums up neoclassical microeconomic theory as the science of "how we choose to use scarce productive resources with alternative uses to meet productive ends". JK Galbraith (probably the greatest economist outside the mainstream who never earned a Prize!) describes the methodological individualism of economic science further as: "people are making decisions on what they will have; firms are deciding how these decisions can best be served. [Classic] Economics studies the behaviour of people so engaged."

Glaringly missing from any such definition is not only an acknowledgement of the embedded nature of the economy within society, but also an appreciation of the emancipative purpose of economics - and the economy - to benefit humankind. Consumption, in the form of marginal utility, is uncritically reified as expression of the "sovereign choice" of free individuals (or citizens in the case of public expenditure); competition in a perfect market is glorified as the vehicle not only for price allocation, but justice; oligopolies are studied, but the increasingly self-interested concentration and abuse of power by big business is ignored; public policy is mainly posited as a vehicle to support full employment and economic growth, not the sustainable well-being of all. Throughout its short history, classical economics has been busily promoting endless variations of technical sophistries - zealous to appear like a "hard science", whilst dismally failing to progress any deeper moral inquiry.

Along that same line, Avner Offer and Gabriel Söderberg analyse the award's history in their book, The Nobel Factor: The Prize in Economics, Social Democracy, and the Market Turn. According to the authors, the Prize clearly favours Economics as a doctrine focused on people's individual interactions with free markets, drawing heavily on abstract theory, mathematical models, and the assumption that people will act in rational self-interest - rather than a paradigm that situates the economy inside society and requires public policy decisions to further sustainable prosperity for all citizens. This is also evident in the word cloud visualising recurrences of themes across motivations for all past awards (based on Nobel Foundation website). Words like "theory", "analysis", and "market" dominate - whilst "human" or "poverty" or "welfare" rarely appear. "Sustainability", "responsibility" or "society" are completely absent.

But maybe things have started to get better? Some social media and newspapers hailed the award to Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer in 2019 for "their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty" as a true turnaround. The Financial Times even claimed that the Nobel "will help restore [the] profession's relevance". Open Democracy remains skeptical: "the interventions considered by the Nobel laureates tend to be removed from analyses of power and wider social change. In fact, the Nobel committee specifically gave it to Banerjee, Duflo and Kremer for addressing "smaller, more manageable questions," rather than big ideas. While such small interventions might generate positive results at the micro-level, they do little to challenge the systems that produce the problems." Open Democracy asks rightly whether the "lack of challenge to the existing economic order is perhaps also precisely one of the secrets to media and donor appeal" - whilst the world is facing large systemic crises, the economics profession is celebrating small technical fixes. In this context, conservative protest against David Card's "surprising and befuddling nomination" as co-recipient of the Nobel Prize for economics in 2021 might be a positive sign: Card received the prize partly for a paper, co-authored by Alan Kreuger, purporting to debunk the consensus among economists that higher minimum wages trigger job losses. The nominating jury emphasized Card's conclusion that a higher minimum wage "does not necessarily lead to fewer jobs".

Of course, die-hard libertarians will continue to point to Adam Smith and suggest that it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, and not even of the banker or the economist that we expect a benefit for humanity, but from the "invisible hand" of perfect markets. Yet, as Joe Stiglitz, himself a laureate in 2001, pointed out: "the reason the invisible hand often seems invisible is… that it is often not there".

Gran Finale: And The Winner is…

So, considering process, winners, and those purported economical "discoveries" during the last five decades, did economical science merit its rather brutal inclusion in Alfred Nobel's legacy?

Undoubtedly, many exceptionally intelligent and influential thinkers were honoured, and maybe a few of the topics had indeed some small influence on wider societal well-being, but I am afraid the honest answer must be: no. Economists (too) seldom are revolutionaries and neither are their textbooks. Overall, the Economics Prize has promoted an insular set of academics and too often put forward an anachronistic and limiting understanding of Economics - rather than igniting and supporting a novel economic eutopia for the benefit of humanity. Economics in its neoclassical tradition purports a simplistic and individualistic morality that falls severely short of Alfred Nobel's ambition to honour innovations that create a purposeful positive impact.

Herein also lies the stark difference between Nobel's rejection of Economics and Hayek's hollow critique of the Prize on the grounds of an individual appointee's limited authority. In Hayek's "neoliberal" axiology, markets are not only "mechanisms of rational allocation of scarce resources among mutually competing ends" but also the" most rational processor of economic information and subjective individual knowledges". Accordingly, "a free person is an ignorant consumerist-entrepreneurial idiot, who wastes no time dwelling on higher truths or grand narratives, but uses only a tiny quantity of specialised knowledge to adapt quickly to changing economic circumstances." As he once posited: "One is no longer required to know why, only how. For everything else, there is the market." Nothing could be further from the character or moral spirit of Alfred Nobel.

But maybe things have started to get better? Some social media and newspapers hailed the award to Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer in 2019 for "their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty" as a true turnaround. The Financial Times even claimed that the Nobel "will help restore [the] profession's relevance". Open Democracy remains skeptical: "the interventions considered by the Nobel laureates tend to be removed from analyses of power and wider social change. In fact, the Nobel committee specifically gave it to Banerjee, Duflo and Kremer for addressing "smaller, more manageable questions," rather than big ideas. While such small interventions might generate positive results at the micro-level, they do little to challenge the systems that produce the problems." Open Democracy asks rightly whether the "lack of challenge to the existing economic order is perhaps also precisely one of the secrets to media and donor appeal" - whilst the world is facing large systemic crises, the economics profession is celebrating small technical fixes. In this context, conservative protest against David Card's "surprising and befuddling nomination" as co-recipient of the Nobel Prize for economics in 2021 might be a positive sign: Card received the prize partly for a paper, co-authored by Alan Kreuger, purporting to debunk the consensus among economists that higher minimum wages trigger job losses. The nominating jury emphasized Card's conclusion that a higher minimum wage "does not necessarily lead to fewer jobs".

Of course, die-hard libertarians will continue to point to Adam Smith and suggest that it is not from the benevolence of the butcher, and not even of the banker or the economist that we expect a benefit for humanity, but from the "invisible hand" of perfect markets. Yet, as Joe Stiglitz, himself a laureate in 2001, pointed out: "the reason the invisible hand often seems invisible is… that it is often not there".

Gran Finale: And The Winner is…

So, considering process, winners, and those purported economical "discoveries" during the last five decades, did economical science merit its rather brutal inclusion in Alfred Nobel's legacy?

Undoubtedly, many exceptionally intelligent and influential thinkers were honoured, and maybe a few of the topics had indeed some small influence on wider societal well-being, but I am afraid the honest answer must be: no. Economists (too) seldom are revolutionaries and neither are their textbooks. Overall, the Economics Prize has promoted an insular set of academics and too often put forward an anachronistic and limiting understanding of Economics - rather than igniting and supporting a novel economic eutopia for the benefit of humanity. Economics in its neoclassical tradition purports a simplistic and individualistic morality that falls severely short of Alfred Nobel's ambition to honour innovations that create a purposeful positive impact.

Herein also lies the stark difference between Nobel's rejection of Economics and Hayek's hollow critique of the Prize on the grounds of an individual appointee's limited authority. In Hayek's "neoliberal" axiology, markets are not only "mechanisms of rational allocation of scarce resources among mutually competing ends" but also the" most rational processor of economic information and subjective individual knowledges". Accordingly, "a free person is an ignorant consumerist-entrepreneurial idiot, who wastes no time dwelling on higher truths or grand narratives, but uses only a tiny quantity of specialised knowledge to adapt quickly to changing economic circumstances." As he once posited: "One is no longer required to know why, only how. For everything else, there is the market." Nothing could be further from the character or moral spirit of Alfred Nobel.

Epilogue: Virtute non astitutia

Which of course leads us to a final and even more fundamental question: could a revamped Economics prize become a worthwhile addition to the Nobel family? Undoubtedly, yes.

The opportunity and the necessity to stimulate an important societal dialogue about the future of work and the role of our economy has never been greater. Business-related issues play a dominating role in both public and private life of people, and businesses themselves are a key enabler of our global commercial and political ecosystems. A virtuous Nobel Prize for Economics could emphasize the need for a radical shift - to re-embed the economy within a good society and economics within the social sciences - and feed a global conversation with new insights about how to construct a better future.

Yet, this is far from where we are today. A recent Guardian article eloquently sums up the challenge: "Perhaps the most pernicious effect of the status of economics in public life has been the hegemony of technocratic thinking. Political questions about how to run society have come to be framed as technical issues, fatally diminishing politics as the arena where society debates means and ends." "Think of how frequently the Nobel Prize for literature elevates little-known writers or poets to the global stage, or how the peace prize stirs up a vital global conversation. Naguib Mahfouz's Nobel introduced Arab literature to a mass audience, while the prize for Kailash Satyarthi and Malala Yousafzai put the right of all children to an education on the agenda. Nobel Prizes in economics, meanwhile, go to "contributions to methods of analysing economic time series with time-varying volatility" (2003) or the "analysis of trade patterns and location of economic activity" (2008)!"

So, let us hope the Royal Academy of Science will come to wiser conclusions on December 10th 2023. If it doesn't, any decent economist should probably act like Jean-Paul Sartre in 1964 when he famously declined the Nobel Prize for literature. Different from Hayek, who very gladly banked the million-dollar cheque and a large boost in citations (one of his biographers admitted that it is doubtful whether his work would have risen to any such prominence without the Prize), Sartre suggested that accepting the award would mean to "let himself be transformed into an institution" and thus "expose his readers to a pressure" that is not desirable. A "Nobel Prize" in Economics that is both genealogically illegitimate and politically unfortunate is an undesirable pressure indeed.

FIN

---

All Winners of the "Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel" 1969–2022

1969 Ragnar Frisch and Jan Tinbergen "for having developed and applied dynamic models for the analysis of economic processes"

1970 Paul A. Samuelson "for the scientific work through which he has developed static and dynamic economic theory and actively contributed to raising the level of analysis in economic science"

1971 Simon Kuznets "for his empirically founded interpretation of economic growth which has led to new and deepened insight into the economic and social structure and process of development"

1972 John R. Hicks and Kenneth J. Arrow "for their pioneering contributions to general economic equilibrium theory and welfare theory"

1973 Wassily Leontief "for the development of the input-output method and for its application to important economic problems"

1974 Gunnar Myrdal and Friedrich August von Hayek "for their pioneering work in the theory of money and economic fluctuations and for their penetrating analysis of the interdependence of economic, social and institutional phenomena"

1975 Leonid Vitaliyevich Kantorovich and Tjalling C. Koopmans "for their contributions to the theory of optimum allocation of resources"

1976 Milton Friedman "for his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy"

1977 Bertil Ohlin and James E. Meade "for their pathbreaking contribution to the theory of international trade and international capital movements"

1978 Herbert A. Simon "for his pioneering research into the decision-making process within economic organizations"

1979 Theodore W. Schultz and Sir Arthur Lewis "for their pioneering research into economic development research with particular consideration of the problems of developing countries"

1980 Lawrence R. Klein "for the creation of econometric models and the application to the analysis of economic fluctuations and economic policies"

1981 James Tobin "for his analysis of financial markets and their relations to expenditure decisions, employment, production and prices"

1982 George J. Stigler "for his seminal studies of industrial structures, functioning of markets and causes and effects of public regulation"

1983 Gerard Debreu "for having incorporated new analytical methods into economic theory and for his rigorous reformulation of the theory of general equilibrium"

1984 Richard Stone "for having made fundamental contributions to the development of systems of national accounts and hence greatly improved the basis for empirical economic analysis"

1985 Franco Modigliani "for his pioneering analyses of saving and of financial markets"

1986 James M. Buchanan Jr. "for his development of the contractual and constitutional bases for the theory of economic and political decision-making"

1987 Robert M. Solow "for his contributions to the theory of economic growth"

1988 Maurice Allais "for his pioneering contributions to the theory of markets and efficient utilization of resources"

1989 Trygve Haavelmo "for his clarification of the probability theory foundations of econometrics and his analyses of simultaneous economic structures"

1990 Harry M. Markowitz, Merton H. Miller and William F. Sharpe "for their pioneering work in the theory of financial economics"

1991 Ronald H. Coase "for his discovery and clarification of the significance of transaction costs and property rights for the institutional structure and functioning of the economy"

1992 Gary S. Becker "for having extended the domain of microeconomic analysis to a wide range of human behaviour and interaction, including nonmarket behaviour"

1993 Robert W. Fogel and Douglass C. North "for having renewed research in economic history by applying economic theory and quantitative methods in order to explain economic and institutional change"

1994 John C. Harsanyi, John F. Nash Jr. and Reinhard Selten "for their pioneering analysis of equilibria in the theory of non-cooperative games"

1995 Robert E. Lucas Jr. "for having developed and applied the hypothesis of rational expectations, and thereby having transformed macroeconomic analysis and deepened our understanding of economic policy"

1996 James A. Mirrlees and William Vickrey "for their fundamental contributions to the economic theory of incentives under asymmetric information"

1997 Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes "for a new method to determine the value of derivatives"

1998 Amartya Sen "for his contributions to welfare economics"

1999 Robert A. Mundell "for his analysis of monetary and fiscal policy under different exchange rate regimes and his analysis of optimum currency areas"

2000 James J. Heckman "for his development of theory and methods for analyzing selective samples"

Daniel L. McFadden "for his development of theory and methods for analyzing discrete choice"

2001 George A. Akerlof, A. Michael Spence and Joseph E. Stiglitz "for their analyses of markets with asymmetric information"

2002 Daniel Kahneman "for having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty"

Vernon L. Smith "for having established laboratory experiments as a tool in empirical economic analysis, especially in the study of alternative market mechanisms"

2003 Robert F. Engle III "for methods of analyzing economic time series with time-varying volatility (ARCH)"

Clive W.J. Granger "for methods of analyzing economic time series with common trends (cointegration)"

2004 Finn E. Kydland and Edward C. Prescott "for their contributions to dynamic macroeconomics: the time consistency of economic policy and the driving forces behind business cycles"

2005 Robert J. Aumann and Thomas C. Schelling "for having enhanced our understanding of conflict and cooperation through game-theory analysis"

2006 Edmund S. Phelps "for his analysis of intertemporal tradeoffs in macroeconomic policy"

2007 Leonid Hurwicz, Eric S. Maskin and Roger B. Myerson "for having laid the foundations of mechanism design theory"

2008 Paul Krugman "for his analysis of trade patterns and location of economic activity"

2009 Elinor Ostrom "for her analysis of economic governance, especially the commons"

Oliver E. Williamson "for his analysis of economic governance, especially the boundaries of the firm"

2010 Peter A. Diamond, Dale T. Mortensen and Christopher A. Pissarides "for their analysis of markets with search frictions"

2011 Thomas J. Sargent and Christopher A. Sims "for their empirical research on cause and effect in the macroeconomy"

2012 Alvin E. Roth and Lloyd S. Shapley "for the theory of stable allocations and the practice of market design"

2013 Eugene F. Fama, Lars Peter Hansen and Robert J. Shiller "for their empirical analysis of asset prices"

2014 Jean Tirole "for his analysis of market power and regulation"

2015 Angus Deaton "for his analysis of consumption, poverty, and welfare"

2016 Oliver Hart and Bengt Holmström "for their contributions to contract theory"

2017 Richard H. Thaler "for his contributions to behavioural economics"

2018 William D. Nordhaus "for integrating climate change into long-run macroeconomic analysis"

Paul M. Romer "for integrating technological innovations into long-run macroeconomic analysis"

2019 Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer "for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty"

2020 Paul R. Milgrom and Robert B. Wilson "for improvements to auction theory and inventions of new auction formats"

2021 David Card "for his empirical contributions to labour economics"

Joshua D. Angrist and Guido W. Imbens "for their methodological contributions to the analysis of causal relationships"

2022 Ben S. Bernanke, Douglas W. Diamond and Philip H. Dybvig "for research on banks and financial crises"

---

Selected sources & further reading

Epilogue: Virtute non astitutia

Which of course leads us to a final and even more fundamental question: could a revamped Economics prize become a worthwhile addition to the Nobel family? Undoubtedly, yes.

The opportunity and the necessity to stimulate an important societal dialogue about the future of work and the role of our economy has never been greater. Business-related issues play a dominating role in both public and private life of people, and businesses themselves are a key enabler of our global commercial and political ecosystems. A virtuous Nobel Prize for Economics could emphasize the need for a radical shift - to re-embed the economy within a good society and economics within the social sciences - and feed a global conversation with new insights about how to construct a better future.

Yet, this is far from where we are today. A recent Guardian article eloquently sums up the challenge: "Perhaps the most pernicious effect of the status of economics in public life has been the hegemony of technocratic thinking. Political questions about how to run society have come to be framed as technical issues, fatally diminishing politics as the arena where society debates means and ends." "Think of how frequently the Nobel Prize for literature elevates little-known writers or poets to the global stage, or how the peace prize stirs up a vital global conversation. Naguib Mahfouz's Nobel introduced Arab literature to a mass audience, while the prize for Kailash Satyarthi and Malala Yousafzai put the right of all children to an education on the agenda. Nobel Prizes in economics, meanwhile, go to "contributions to methods of analysing economic time series with time-varying volatility" (2003) or the "analysis of trade patterns and location of economic activity" (2008)!"

So, let us hope the Royal Academy of Science will come to wiser conclusions on December 10th 2023. If it doesn't, any decent economist should probably act like Jean-Paul Sartre in 1964 when he famously declined the Nobel Prize for literature. Different from Hayek, who very gladly banked the million-dollar cheque and a large boost in citations (one of his biographers admitted that it is doubtful whether his work would have risen to any such prominence without the Prize), Sartre suggested that accepting the award would mean to "let himself be transformed into an institution" and thus "expose his readers to a pressure" that is not desirable. A "Nobel Prize" in Economics that is both genealogically illegitimate and politically unfortunate is an undesirable pressure indeed.

FIN

---

All Winners of the "Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel" 1969–2022

1969 Ragnar Frisch and Jan Tinbergen "for having developed and applied dynamic models for the analysis of economic processes"

1970 Paul A. Samuelson "for the scientific work through which he has developed static and dynamic economic theory and actively contributed to raising the level of analysis in economic science"

1971 Simon Kuznets "for his empirically founded interpretation of economic growth which has led to new and deepened insight into the economic and social structure and process of development"

1972 John R. Hicks and Kenneth J. Arrow "for their pioneering contributions to general economic equilibrium theory and welfare theory"

1973 Wassily Leontief "for the development of the input-output method and for its application to important economic problems"

1974 Gunnar Myrdal and Friedrich August von Hayek "for their pioneering work in the theory of money and economic fluctuations and for their penetrating analysis of the interdependence of economic, social and institutional phenomena"

1975 Leonid Vitaliyevich Kantorovich and Tjalling C. Koopmans "for their contributions to the theory of optimum allocation of resources"

1976 Milton Friedman "for his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy"

1977 Bertil Ohlin and James E. Meade "for their pathbreaking contribution to the theory of international trade and international capital movements"

1978 Herbert A. Simon "for his pioneering research into the decision-making process within economic organizations"

1979 Theodore W. Schultz and Sir Arthur Lewis "for their pioneering research into economic development research with particular consideration of the problems of developing countries"

1980 Lawrence R. Klein "for the creation of econometric models and the application to the analysis of economic fluctuations and economic policies"

1981 James Tobin "for his analysis of financial markets and their relations to expenditure decisions, employment, production and prices"

1982 George J. Stigler "for his seminal studies of industrial structures, functioning of markets and causes and effects of public regulation"

1983 Gerard Debreu "for having incorporated new analytical methods into economic theory and for his rigorous reformulation of the theory of general equilibrium"

1984 Richard Stone "for having made fundamental contributions to the development of systems of national accounts and hence greatly improved the basis for empirical economic analysis"

1985 Franco Modigliani "for his pioneering analyses of saving and of financial markets"

1986 James M. Buchanan Jr. "for his development of the contractual and constitutional bases for the theory of economic and political decision-making"

1987 Robert M. Solow "for his contributions to the theory of economic growth"

1988 Maurice Allais "for his pioneering contributions to the theory of markets and efficient utilization of resources"

1989 Trygve Haavelmo "for his clarification of the probability theory foundations of econometrics and his analyses of simultaneous economic structures"

1990 Harry M. Markowitz, Merton H. Miller and William F. Sharpe "for their pioneering work in the theory of financial economics"

1991 Ronald H. Coase "for his discovery and clarification of the significance of transaction costs and property rights for the institutional structure and functioning of the economy"

1992 Gary S. Becker "for having extended the domain of microeconomic analysis to a wide range of human behaviour and interaction, including nonmarket behaviour"

1993 Robert W. Fogel and Douglass C. North "for having renewed research in economic history by applying economic theory and quantitative methods in order to explain economic and institutional change"

1994 John C. Harsanyi, John F. Nash Jr. and Reinhard Selten "for their pioneering analysis of equilibria in the theory of non-cooperative games"

1995 Robert E. Lucas Jr. "for having developed and applied the hypothesis of rational expectations, and thereby having transformed macroeconomic analysis and deepened our understanding of economic policy"

1996 James A. Mirrlees and William Vickrey "for their fundamental contributions to the economic theory of incentives under asymmetric information"

1997 Robert C. Merton and Myron S. Scholes "for a new method to determine the value of derivatives"

1998 Amartya Sen "for his contributions to welfare economics"

1999 Robert A. Mundell "for his analysis of monetary and fiscal policy under different exchange rate regimes and his analysis of optimum currency areas"

2000 James J. Heckman "for his development of theory and methods for analyzing selective samples"

Daniel L. McFadden "for his development of theory and methods for analyzing discrete choice"

2001 George A. Akerlof, A. Michael Spence and Joseph E. Stiglitz "for their analyses of markets with asymmetric information"

2002 Daniel Kahneman "for having integrated insights from psychological research into economic science, especially concerning human judgment and decision-making under uncertainty"

Vernon L. Smith "for having established laboratory experiments as a tool in empirical economic analysis, especially in the study of alternative market mechanisms"

2003 Robert F. Engle III "for methods of analyzing economic time series with time-varying volatility (ARCH)"

Clive W.J. Granger "for methods of analyzing economic time series with common trends (cointegration)"

2004 Finn E. Kydland and Edward C. Prescott "for their contributions to dynamic macroeconomics: the time consistency of economic policy and the driving forces behind business cycles"

2005 Robert J. Aumann and Thomas C. Schelling "for having enhanced our understanding of conflict and cooperation through game-theory analysis"

2006 Edmund S. Phelps "for his analysis of intertemporal tradeoffs in macroeconomic policy"

2007 Leonid Hurwicz, Eric S. Maskin and Roger B. Myerson "for having laid the foundations of mechanism design theory"

2008 Paul Krugman "for his analysis of trade patterns and location of economic activity"

2009 Elinor Ostrom "for her analysis of economic governance, especially the commons"

Oliver E. Williamson "for his analysis of economic governance, especially the boundaries of the firm"

2010 Peter A. Diamond, Dale T. Mortensen and Christopher A. Pissarides "for their analysis of markets with search frictions"

2011 Thomas J. Sargent and Christopher A. Sims "for their empirical research on cause and effect in the macroeconomy"

2012 Alvin E. Roth and Lloyd S. Shapley "for the theory of stable allocations and the practice of market design"

2013 Eugene F. Fama, Lars Peter Hansen and Robert J. Shiller "for their empirical analysis of asset prices"

2014 Jean Tirole "for his analysis of market power and regulation"

2015 Angus Deaton "for his analysis of consumption, poverty, and welfare"

2016 Oliver Hart and Bengt Holmström "for their contributions to contract theory"

2017 Richard H. Thaler "for his contributions to behavioural economics"

2018 William D. Nordhaus "for integrating climate change into long-run macroeconomic analysis"

Paul M. Romer "for integrating technological innovations into long-run macroeconomic analysis"

2019 Abhijit Banerjee, Esther Duflo and Michael Kremer "for their experimental approach to alleviating global poverty"

2020 Paul R. Milgrom and Robert B. Wilson "for improvements to auction theory and inventions of new auction formats"

2021 David Card "for his empirical contributions to labour economics"

Joshua D. Angrist and Guido W. Imbens "for their methodological contributions to the analysis of causal relationships"

2022 Ben S. Bernanke, Douglas W. Diamond and Philip H. Dybvig "for research on banks and financial crises"

---

Selected sources & further reading

Popular articles in the KnowledgeHub: Critical Thinking

.

.