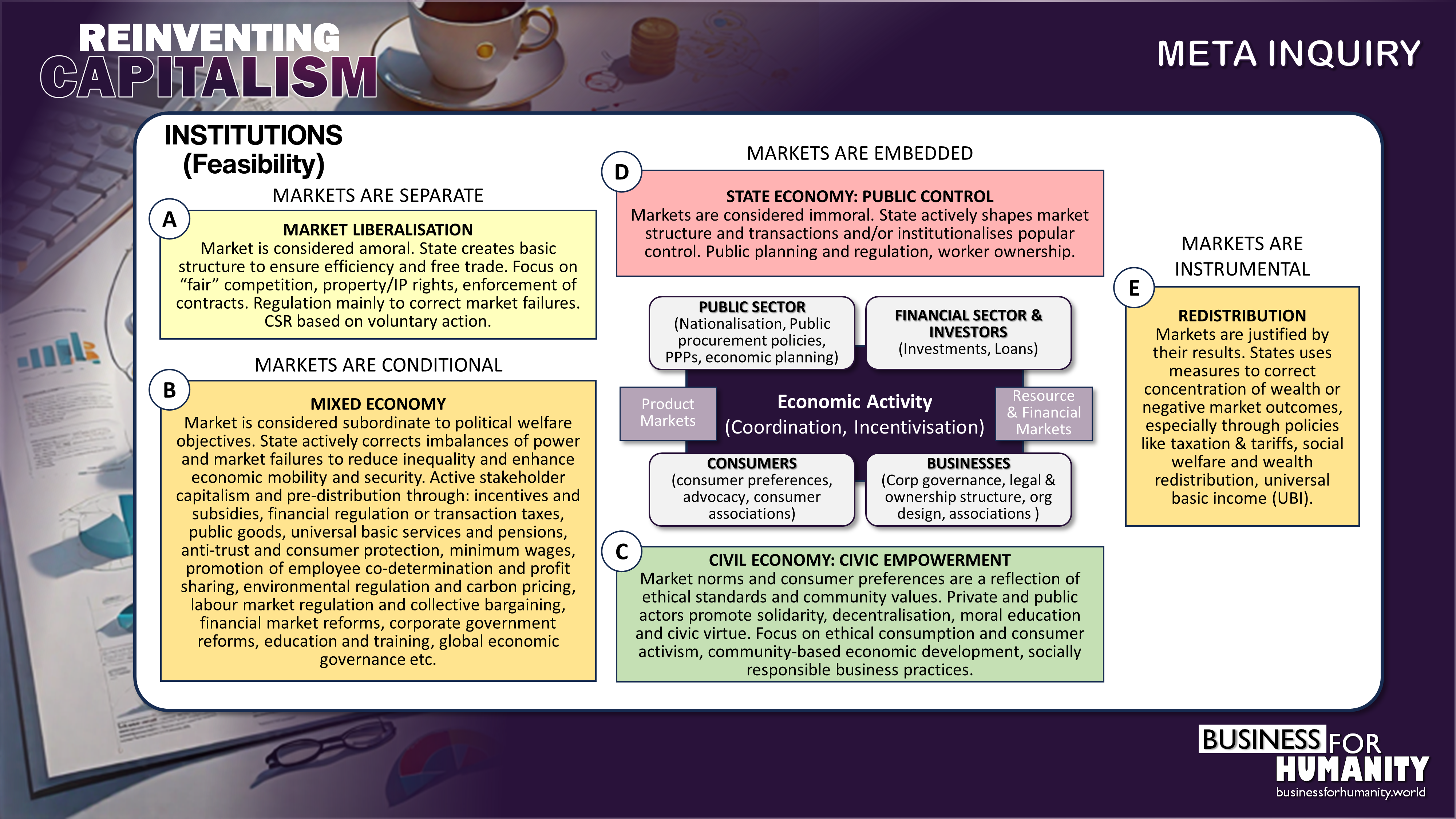

Political/Economic Institutions

While generally critical of regulation, Pieconomics advocates for regulatory frameworks that address externalities, redistribute benefits from pie growth, and facilitate the dissemination of best practices. It suggests some regulatory reforms aimed at reducing short-termism in financial markets, such as changes to accounting standards, taxation policies, and corporate reporting requirements. Furthermore, it underscores the collective responsibility of the investment management industry in promoting social stewardship, emphasizing the role of shareholders, proxy advisors, financial analysts and asset managers in driving positive change through long-term financial incentives and dedicated stewardship resources.

Corporate Governance

Pieconomics underscores the significance of robust corporate governance mechanisms, advocating for active investor engagement to enhance governance standards and ensure management decisions prioritize long-term value creation and accountability to stakeholders.

- Long-term oriented stewardship: Pieconomics highlights the value of investor engagement and monitoring in driving positive outcomes for society. It suggests that purposeful and concentrated hedge funds, backed by substantial resources and incentivized for long-term performance, can effectively provided specialist engagement with and monitoring of companies to promote (social) value creation and discipline underperformance. Additionally, it acknowledges the role of mutual funds in offering generalised engagement, and of large long-term investors or blockholders in shielding companies from short-term pressures. It suggests that protection from shareholder pressure may have varying impacts depending on the circumstances, suggesting a need for tailored investor rights.

- Alignment of Incentives: Pieconomics advocates for aligning the interests of managers and shareholders with long-term value creation through strategies such as offering restricted long-term stock, which would be held even after retirement. It critiques the negative effects of LTIPs, complex bonuses, and performance conditions, suggesting that they can hinder long-term value creation. Additionally, it argues against limitations on CEO pay, asserting that compensation are relatively small compared to enterprise value and are not detrimental to employee compensation or effective in addressing social inequality.

- Share buybacks: Pieconomics offers a nuanced perspective on share buybacks, highlighting their potential benefits when used strategically, such as investing in own stock during periods of low investment opportunities and surplus cash. It suggests that buybacks can be a preferable method for returning surplus cash compared to dividends, as they are flexible and can target investors with less long-term orientation. However, Pieconomics acknowledges evidence suggesting that buybacks can destroy value, particularly when driven by short-term earnings forecasts or equity vesting considerations.

- Transparency and Disclosure: Pieconomics emphasizes the importance of transparent reporting and disclosure practices, particularly regarding environmental, social, and governance (ESG) metrics, to enable investors and stakeholders to assess a company's long-term sustainability and societal impact accurately. It advocates the use of qualitative indicators next to quantitative ones and it cautions against some practices such reporting of quarterly earnings which tend to strengthen short-termism.

Organisations

Pieconomics advocates for businesses to prioritize operational excellence as the best form of service over philanthropic efforts. This requires businesses to set and communicate a clear and shared purpose. A purpose statement should define the company's reason for existence and who it serves, extending beyond just customers while being focused and selective to enable the prioritization of investments and efforts. The purpose should be both deliberate and emergent, integrating top-down and bottom-up perspectives. Additionally, enterprises should establish long-term targets for each stakeholder purpose and incorporate purpose into various aspects of their operations, including strategy, operating models, culture, reporting, and governance.

- Stakeholder Engagement: Pieconomics advocates for companies to actively engage with a diverse array of stakeholders, viewing them as partners in enhancing stakeholder capital. He proposes implementing a "say-on-purpose" mechanism for investors and establishing a dedicated board committee focused on corporate responsibility.

- Measuring Impact: Pieconomics recommends that companies measure their societal impact alongside financial performance. This entails developing metrics for ESG factors alongside financial outcomes. Initiatives like the Embankment Project for Inclusive Capitalism offer frameworks for assessing impact across various stakeholder groups, which should be seamlessly integrated with narrative and company-specific data.

- Employee Ownership and Engagement: Emphasizing the pivotal role of employee ownership and engagement in driving organizational success, Pieconomics suggests empowering employees through ownership, investment, and rewards such as company shares. When employees feel a sense of ownership and are actively involved in decision-making processes, they are more inclined to positively contribute to the company's performance.

- Leadership and Culture: The approach underscores the significance of leadership and culture in shaping a company's approach to balancing purpose and profit.

Investment decisions

Pieconomics acknowledges the importance of profits as societal indicators but emphasizes leaders' intrinsic motivations to serve society, recognizing the limitations of instrumental and quantitative financial decision-making, particularly in uncertain or intangible contexts. It warns against a profit-maximizing mindset that may result in minimal investment for social value, failing to differentiate the company positively. While some actions may not directly maximize profits, Pieconomics contends that most value eventually translates into financial value in the long run, particularly if material stakeholder interests are taken into account.

Under Pieconomics, value creation hinges on ensuring that the benefits of investments outweigh their costs, with companies deploying societal resources only when they generate greater benefits than alternative uses, thereby maximizing overall social value. Leaders are urged to adhere to three investment principles: a) multiplication: ensuring that social value surpasses company costs, b) comparative advantage: that it social value exceeds opportunity costs (compared to other companies utilizing equivalent resources), and c) materiality: that investments are relevant to the core business (e.g. deploying "materiality maps"). This approach acknowledges that companies typically have comparative advantages in their own activities or specific areas of expertise, although tough prioritizations may at times be necessary, potentially involving compensating "losing" stakeholders. Overall, the company should deliver a "net benefit" to society, adding up the positive and negative effects on each stakeholder, weighed by materiality.

.

.